Peruvian Lily (Alstroemeria aurea)

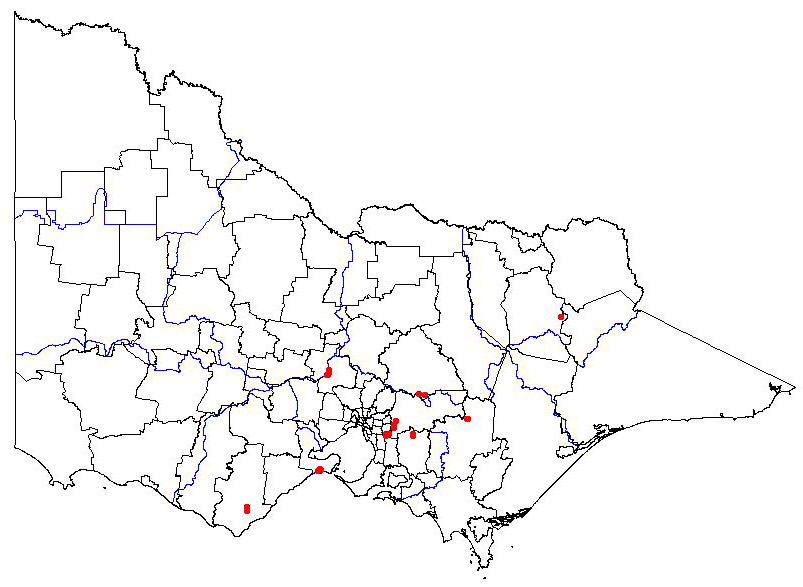

Present distribution

|  Map showing the present distribution of this weed. | ||||

| Habitat: Native to Argentina & Chile. In Argentina, found occurring in Nothofagus Antarctica shrubland & N. pumilio forest (including ‘old-growth’ forest) from 1050 to 1550 m, and in cleared ski run zones (Aizen 2001; Puntieri 1991). In Victoria, a successful weed in the Dandenongs, Mt Macedon and established at a site near Falls Creek (LFR UniMelb). It is identified as having invaded damp and wet sclerophyll forest and riparian vegetation (Carr, Yugovic & Robinson 1992) and being locally abundant in gullies and shady, moist sites (Richardson 2006). | |||||

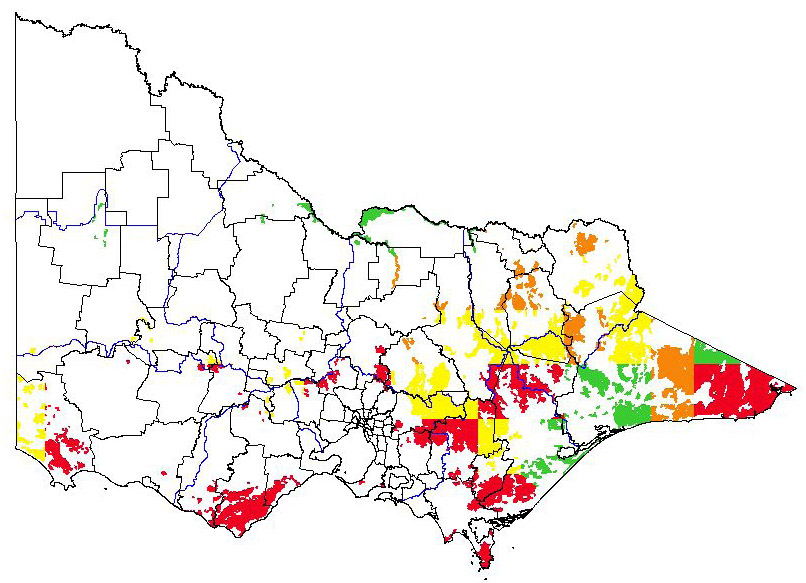

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Forest private plantation; forest public plantation Broad vegetation types Lowland forest; swamp scrub; sedge rich woodland; moist foothills forest; montane dry woodland; montane moist forest; sub-alpine woodland; valley grassy forest; sub-alpine grassy woodland; montane grassy woodland; riverine grassy woodland; riparian forest Colours indicate possibility of Alstroemeria aurea infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | A species to 1.2 m tall (Puntieri 1991) forming dense populations of up to 200 shoots per m2 (Weber 2003). Significant height and density could impede individual access but likely to have fairly low nuisance value. | ML | M |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | Minor effects to aesthetics due to its ability to dominate the understorey and form pure monocultures (Aizen 2001). | ML | MH |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Causes allergic dermatitis, rashes on fingers, hands, arms and face when handled. All parts, especially flowers leaves and stems cause allergies (Shepherd 2004). Mildly toxic. | ML | MH |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | Moderate visual effect due to its ability to dominate the understorey and form pure monocultures (Aizen 2001). | ML | M |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Terrestrial species, no impact on water flow. | L | H |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Terrestrial species, no impact on water flow. | L | H |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | Species forms dense populations of up to 200 shoots per m2 (Weber 2003). No evidence to suggest it would increase soil erosion. | L | MH |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | Species forms dense populations of up to 200 shoots per m2 (Weber 2003). Understorey biomass may increase. | L | M |

| 9. Change fire regime? | No information was found documented of its affect on fire frequency or intensity. | M | L |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC= Cool Temperate Rainforest (BCS= E); CMA= West Gippsland; Bioreg= Strzelecki Ranges; CLIMATE potential= VH. Substantially reduces regeneration opportunities of native plants (Platt et al 2005) Crowds out and prevents the establishment of native plants (Weber 2003). A ‘very serious threat to one or more vegetation formations in Victoria (Carr, Jugovic & Robinson 1992). Major displacement of some dominant species within lower strata. | MH | MH |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC= Wet Forest (BCS= D); CMA= West Gippsland; Bioreg= Strzelecki Ranges; CLIMATE potential= VH. Substantially reduces regeneration opportunities of native plants (Platt et al 2005) Crowds out and prevents the establishment of native plants (Weber 2003). A ‘very serious threat to one or more vegetation formations in Victoria (Carr, Jugovic & Robinson 1992)’. Major displacement of some dominant species within lower strata. | MH | MH |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC= Montane Damp Forest (BCS= LC); CMA= West Gippsland; Bioreg= Highlands-Southern Fall; CLIMATE potential= VH. Substantially reduces regeneration opportunities of native plants (Platt et al 2005) Crowds out and prevents the establishment of native plants (Weber 2003). A ‘very serious threat to one or more vegetation formations in Victoria (Carr, Jugovic & Robinson 1992)’. Major displacement of some dominant species within lower strata. | MH | MH |

| 11. Impact on structure? | Changes light distribution and substantially reduces regeneration opportunities of native plants (Platt et al 2005) Crowds out and prevents the establishment of native plants (Weber 2003). A ‘very serious threat to one or more vegetation formations in Victoria (Carr, Jugovic & Robinson 1992)’. Major effect on lower strata (<60% of the floral strata). | MH | MH |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | Crowds out and prevents the establishment of native plants (Weber 2003). A ‘very serious threat to one or more vegetation formations in Victoria (Carr, Jugovic & Robinson 1992). No information was documented in regards to its specific threat on threatened flora | MH | L |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | No information was documented in regards to its impact on threatened fauna. | MH | L |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | Substantially reduces regeneration opportunities of native plants (Platt et al 2005) Crowds out and prevents the establishment of native plants (Weber 2003). A decrease in the diversity and cover of native plants is likely to negatively impact on native fauna by reducing food source and habitat. No specific information was documented. | M | ML |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | No information was found documented on its benefits to fauna. | M | L |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | Causes allergic dermatitis in humans, rashes on fingers, hands, arms and face when handled. All parts, especially flowers, leaves and stems cause allergies (Shepherd 2004). May also have an affect on some fauna but no information was documented regarding its injurious nature to fauna. | M | L |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | Plant contains toxins that cause allergic dermatitis in humans when handled. All parts, especially flowers, leaves and stems cause allergies (Shepherd 2004). It is possible that these toxins may result in the plant also being poisonous if consumed or unpalatable. However there is no information documented as to whether or not this plant provides a food source to pests. | M | L |

| 18. Provides harbour? | A herb species to 1.2 m tall (Puntieri 1991) forming dense populations of up to 200 shoots per m2 (Weber 2003). This species, due to its moderate height and dense habit, has the capacity to harbour smaller pest species but no information was documented. | M | M |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | Not known as an agricultural weed. | L | M |

| 20. Impact quality? | Not known as an agricultural weed. | L | M |

| 21. Affect land value? | Not known as an agricultural weed, little or no affect on land value. | L | M |

| 22. Change land use? | Not known as an agricultural weed, little or no change in priority of land use. | L | M |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | Not known as an agricultural weed. | L | M |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Viruses found in Alstroemeria include Tomato spotted wilt virus (Bellardi, Bertaccini & Betti 1994) and Tobacco rattle virus (Hakkaart & Versluijs 1985). Tomato spotted wilt virus causes serious diseases of many economically important plants including ornamentals, vegetables, and field crops (Zitter & Daughtrey 1989). Tobacco rattle virus can cause reduction in vigour and yield in various vegetable and bulb crops leading to economic loss (Bruun-Rasmussen & Sundelin 2001). The extent that A. aurea specifically, is a host of these viruses is not clear. | M | L |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | ‘The increased germination of the warm-cold treatment suggests that there are physiological factors in the seed coat that are responsive to cold stratification…’ (King and Bridgen 1990). Suggests natural seasonal disturbances, ie, cold winter temperatures, are required for germination. | MH | MH |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | It is a very common species in the forest understorey (Puntieri 1991). ‘…experiments suggest it will grow and flower happily under 90% shade’ (LFR UniMelb). Can establish under moderate canopy cover. | MH | H |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Documented as invading damp & wet sclerophyll forest and riparian vegetation (Carr, Yugovic & Robinson 1992) and forest edges, riparian habitats and disturbed places (Weber 2003). Establishes in disturbed sites but also relatively intact or only minor disturbed natural ecosystems. | MH | MH |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Rhizomatous geophyte (Carr, Yugovic & Robinson 1992) to 1.2m (Puntieri 1991). Lifeform: Geophyte. | ML | MH |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | No information was found documented in regards to this species’ allelopathic properties. | M | L |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | In one study it recovered from vegetative-shoot cutting by producing new shoots and curtailing the development of reproductive shoots (Puntieri 1991). Herbivory would likely elicit a similar growth response. In its natural range, a blotch leaf miner can completely damage most leaves of vegetative and reproductive shoots prior to flowering, and defoliated shoots were found to sire fewer seeds (Aizen & Raffaele 1998). Reproduction inhibited by herbivory but still capable of vegetative propagule production. | ML | MH |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | ‘This species is so prolific that large clumps can be dug up in late Summer for re-establishment (PFAF)’. An indication that this species is fast growing, however, no specific information was found documented on its growth rate. A medium rating has been assigned. | M | M |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Likely to be frost tolerant being found in mountainous areas and documented on a ski run between 1050 and 1550m (Puntieri 1991) Can tolerate temperatures down to –10o and –15o C (PFAF). Can tolerate drought and maritime exposure (PFAF). Tolerant of frost and drought and perhaps salinity. Its response to fire and waterlogging were not found documented. | ML | MH |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | A clonal plant that propagates vegetatively via rhizome branching and fragmentation and sexually via seed (Aizen & Raffaele 1998). Seed and vegetative reproduction. | H | H |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | Plants produce usually a single inflorescence composed of 2-8 flowers. Capsules produce up to 20 seeds (Aizen 2001) so approximately 160 seeds could be produced per plant. 50- 1000 propagules | ML | H |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | No information on propagule longevity was found documented. | M | L |

| 12. Reproductive period? | It is a clonal plant propagating vegetatively by rhizome branching (Aizen & Raffaele 1998) and can dominate the understorey forming almost pure monocultures (Aizen 2001). Species forms self-sustaining monocultures. | H | MH |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | ‘On occasions plants grown from seed will bloom during the first year…’ (Dave’s garden). ‘…each season an underground rhizome produces a series of vegetative shoots…’ (Aizen 2001). An indication it can reproduce sexually and vegetatively in around a year. Produces propagules between 1-2 years after germination. | MH | MH |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Dispersed by water (Carr, Yugovic & Robinson 1992). Dehiscence is explosive and seeds are thrown a considerable distance from the plant (Sanso & Xifreda 2001; Aizen 2001). Popular cutflower and ornamental species (Mobot; Weber 2003) becoming ‘garden escape’ in south-east Victoria (Richardson 2006). Propagules spread by gravity, deliberate human dispersal and water. | MH | MH |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | Deliberate human dispersal could disperse propagules considerable distance, however, in a naturalised situation seeds would disperse mostly by gravity and also water (found in riparian situations). Very few to none will disperse to 1km. | ML | MH |

References

Aizen, M 2001, ‘Flower sex ratio, pollinator abundance, and the seasonal pollination dynamics of a protandrous plant’, Ecology, vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 127-144.

Aizen, M & Raffaele, E 1998, ‘ Flowering-shoot defoliation affects pollen grain size and post pollination performance in Alstroemeria aurea’, Ecology, vol. 79, no. 6, pp. 2133-2142.

Bellardi, MG, Bertaccini, A & Betti, L 1994, ‘Survey of viruses infecting Alstroemeria in Italy’, Acta Horticulturae, vol. 377, pp. 73-80.

Bruun-Rasmussen, M & Sundelin, T 2001, Tobacco Rattle Virus, Plant Virology, The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, viewed: 12 December 2006, http://www.dias.kvl.dk/Plantvirology/TRVforweb.htm

Carr, GW, Yugovic, JV & Robinson, KE 1992, Environmental weed invasions in Victoria: conservation and management implications, Department of Conservation and Environment, East Melbourne & Ecological Horticulture P/L, Clifton Hill, Victoria.

Falls Creek Vegetation and Weed Management Policy, February 2004, viewed: 12 December 2006, http://www.fallscreek.com.au/downloads/Falls_Creek_Vegetation_&_Weed_Management_Policy_2004.pdf

Hakkaart, FA & Versluijs, JMA 1985, ‘Viruses of Alstroemeria and preliminary results of meristem culture’, Acta Horticulturae, vol. 164, pp. 71-75.

Institute of Land and Food Resources (LFR UniMelb) 2004, Research: Weed Ecology & Management, Institute of Land and Food Resources, University of Melbourne, viewed: 21 November 2006, http://www.landfood.unimelb.edu.au/research/planteco/weed.html

King, JJ & Bridgen, MP 1990, ‘Environmental and Genotypic Regulation of Alstroemeria seed germination’, HortScience, vol. 25, no. 12, pp. 1607- 1609.

Missouri Botanical Garden 2006, Plant Finder: Kemper Centre for Home Gardening, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, viewed: 23 October 2006 http://www.mobot.org/gardeninghelp/plantfinder/Plant.asp?code=A436

Plants for a Future (PFAF) 2004, Database report: Alstroemeria aurea, Plants for a Future, England/Wales, UK, viewed: 23 October 2006,

http://www.pfaf.org/database/plants.php?Alstroemeria+aurea

Platt, S, Adair, R, White, M & Sinclair, S (2005), Regional priority setting for weed management on public land in Victoria: Second Victorian Weeds Conference: Smart weed control, managing for success: Weed Society of Victoria Inc.

Puntieri, JG 1991, ‘Vegetation response on a forest slope cleared for a ski run with special reference to the herb Alstroemeria aurea Graham (Alstroemeriaceae), Argentina’, Biological Conservation, vol. 56, pp. 207-221.

Richardson, RG & Richardson, FJ 2006, Weeds of the south-east: an identification guide to Australia, RG & FJ Richardson, Meredith, Victoria.

Sanso, AM & Xifreda, CC 2001, ‘Generic Delimitation between Alstroemeria and Bomarea (Alstroemeriaceae)’, Annals of Botany, vol. 88, pp. 1057-1069.

Shepherd, RCH 2004, Pretty but Poisonous: Plants Poisonous to People-An Illustrated Guide for Australia, R.G. and F.J. Richardson, Meredith, Victoria.

Swarbrick, JT & Skarratt, DB 1994, The bushweed 2 database of environmental weeds in Australia, The University of Queensland Gatton College.

Weber, E 2003, Invasive Plant Species of the World: A reference guide to Environmental weeds, Cabi Publishing, Wallingford, UK.

Zitter TA & Daughtrey ML 1989, Vegetable MD Online (Fact Sheet Page: 735.90), Department of Plant Pathology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, viewed: 12 December 2006, http://vegetablemdonline.ppath.cornell.edu/factsheets/Virus_SpottedWilt.htm

Global present distribution data references

Aizen, M 2001, ‘Flower sex ratio, pollinator abundance, and the seasonal pollination dynamics of a protandrous plant’, Ecology, vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 127-144.

Aizen, M & Raffaele, E 1998, ‘ Flowering-shoot defoliation affects pollen grain size and post pollination performance in Alstroemeria aurea’, Ecology, vol. 79, no. 6, pp. 2133-2142.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2006, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed: 23 October 2006, http://www.gbif.org/

National Biodiversity Network 2004, NBN Gateway, National Biodiversity Network, UK viewed 23 October 2006, http://www.searchnbn.net/index_homepage/index.jsp

Puntieri, JG 1991, ‘Vegetation response on a forest slope cleared for a ski run with special reference to the herb Alstroemeria aurea Graham (Alstroemeriaceae), Argentina’, Biological Conservation, vol. 56, pp. 207-221.

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.