Brazilian pepper tree (Schinus terebinthifolius)

Present distribution

|  This weed is not known to be naturalised in Victoria | ||||

| Habitat: Native to Brazil, Argentina & Paraguay, growing from sea level to over 700 m elevation. In Florida it grows on range of moist to mesic sites, in pinelands, saw-grass marshes, hammocks and mangrove forest and in disturbed sites, roadsides, agricultural and drainage areas (Ferriter 1997). In Queensland it occurs on waterlogged/ poorly drained soils in coastal areas (Ensbey 2002) and formed understorey in stands of Casuarina glauca and along edges of mangrove forest. It invades early successional wetland and riparian vegetation (Csurches & Edwards 1998). Most invasive in moist conditions but also tolerates dry conditions (Brooks 2001). | |||||

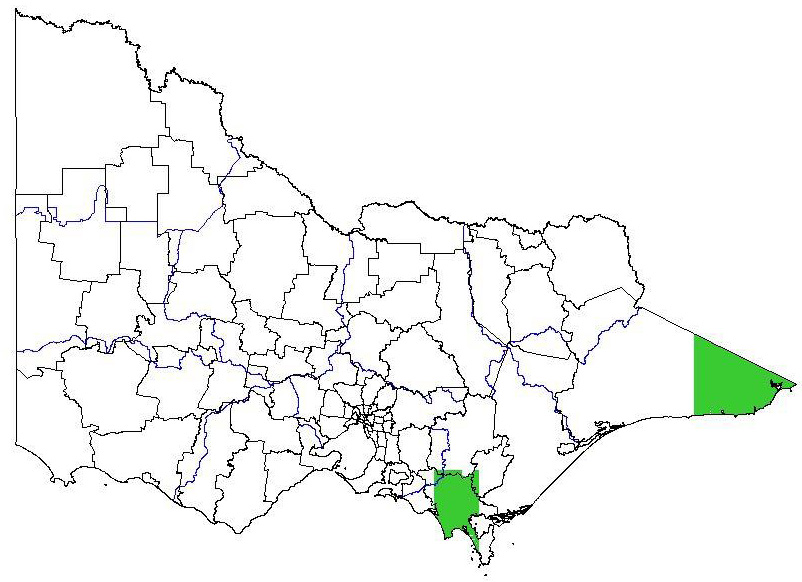

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Forest private plantation; forest public plantation; pasture dryland; pasture irrigation Broad vegetation types Coastal scrubs and grassland; coastal grassy woodland; heathy woodland; lowland forest; heath; swamp scrub; inland slopes woodland; sedge rich woodland; dry foothills forest; moist foothills forest; montane dry woodland; montane moist forest; grassland; plains grassy woodland; valley grassy forest; herb-rich woodland; montane grassy woodland; riverine grassy woodland; riparian forest; rainshadow woodland; mallee; mallee heath; boinka-raak; mallee woodland; wimmera / mallee woodland Colours indicate possibility of Schinus terebinthifolius infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Has long arching branches that often reach the ground forming an impenetrable tangle surrounding the tree to ground level (Ewel et al 1982 in Ferriter 1997). Forms dense woody barricades (NCWAC 2001). Dense stands could significantly restrict waterway and/or machinery access. | H | MH |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | ‘…may ultimately negatively impact Florida’s tourist industry …Any minimisation of the spread of Brazilian Peppers in these areas would maintain the interest of such visitors…’ (Ferriter 1997). Potential to have major impact on recreation if it is considered it will impact on the tourist industry of an entire U.S. state. Weeds would be obvious to most visitors. | H | M |

| 3. Injurious to people? | A relative of poison ivy, direct contact with the sap can cause severe & persistent skin irritation. Airborne chemical emissions from the blooms can cause sinus and nasal congestion, rhinitis, chest pain, sneezing, acute headaches & eye irritation. Tripterenes found in the fruits can result in irritation of the throat, gastroenteritis, and vomiting (Ferriter 1997). Potential for flowers to be present in all months (Morton 1978) and ripe fruits are obtained on a tree for up to 8 months (Ferrier 1997). Serious allergic reactions caused by fruit, flowers and sap of tree, possible throughout the year. | H | MH |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | Its dense growth habit and substantial height (3-7 m +) (Ferriter 1997), could pose a moderate negative visual effect on cultural sites. | ML | MH |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | It is able to grow in areas inundated for up to 3- 6 months (Ferriter 1997) and could therefore occur within ephemeral riparian systems. It is likely to have some impact on water flow due to its dense habit and substantial size. The extent of its impact is not known so a medium rating has been allocated. | M | M |

| 6. Impact water quality? | There is no evidence to suggest it has an impact on water quality. | L | MH |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | There is no evidence documented to suggest this species increases soil erosion. Its capacity to produce dense thickets, characteristic multi stemmed habit and ability to reproduce by root suckers, (Meyer 2005) suggests it may aid in reducing soil movement in some situations. | L | M |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | It rapidly colonises disturbed bushland and can form dense thickets, dominating the understorey. It out-competes and replaces native grasses, ground covers and shrubs (Ensbey 2002). Due to the plants substantial height and ability to form dense thickets (Morton 1978), an increase in biomass may occur when it replaces native understorey vegetation. | L | M |

| 9. Change fire regime? | Reduces the frequency and alters the mean intensity of fires, lowering species diversity (Ewe 2001). In one study an ‘extremely hot” prescribed fire decreased in severity when it reached Brazilian Pepper stands. There was little fire spread into stands and they were only patchily burnt (Meyer 2005). Research suggests a moderate change to both frequency and intensity of fire risk. | MH | MH |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC= Swamp Scrub (BCS= E); CMA= East Gippsland; Bioreg= East Gippsland Lowlands; CLIMATE potential=L. It can form dense thickets dominating understorey vegetation, out-competing and replacing native grasses, ground covers and shrubs (Ensbey 2002). Major displacement of some dominant spp. within the lower & middle strata. | M | M |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC= Riparian Shrubland (BCS= R); CMA= East Gippsland; Bioreg= East Gippsland Lowlands; CLIMATE potential=L. It can form dense thickets dominating understorey vegetation, out-competing and replacing native grasses, ground covers and shrubs (Ensbey 2002). Major displacement of some dominant spp. within the lower & middle strata. | M | M |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC= Wet Heathland (BCS= LC); CMA= East Gippsland; Bioreg= East Gippsland Lowlands; CLIMATE potential=L. It can form dense thickets dominating understorey vegetation, out-competing and replacing native grasses, ground covers and shrubs (Ensbey 2002). Major displacement of some dominant spp. within the lower & middle strata. | M | M |

| 11. Impact on structure? | In Queensland it has formed an understorey within mature stands of Casuarina glauca (swamp oak) (Csurches & Edwards 1998). It can form dense thickets dominating understorey vegetation, out-competing and replacing native grasses, ground covers and shrubs (Ensbey 2002). Unlike many pioneer species, recruitment has continued under a closed canopy, resulting in a self-maintaining stand (Ferriter 1997). It has a major effect on the understorey including shrub layer (lower & middle strata) and ability to form monoculture under a native canopy. | MH | MH |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | In the USA it has displaced some populations of rare listed species, such as the Beach Jacquemontia (Jacquemontia reclinata), and Beach Star (Remirea maritima) (CAIP). Documented to have replaced populations of threatened flora. | MH | M |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | There is evidence to suggest that Brazilian pepper spread is threatening the nesting habitat of the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus), a species threatened in Florida (Ferriter 1997). A reduction in breeding habitat for a threatened species would likely lead to a decrease in population numbers. | MH | M |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | Avian species diversity and total population density is found to decline in stands of Brazilian Pepper and it eliminates many indigenous sources of food for wildlife. It is also known to have toxic effects on some birds and mammals (Ferriter 1997). It produces shady habitat, repelling other plant species and discouraging colonisation by native fauna (ISSG). A reduction in habitat and food source for fauna species, leading to a reduction in numbers of individuals. | MH | MH |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | ‘Raccoons and possibly opossums are known to ingest the fruits…’ (Ewel et al 1982 in Ferriter 1997). Silvereyes are known to consume the fruits (Panetta & McKee 1997). Mockingbirds, cedar-birds and, especially robins in mid-winter, feed heavily on ripe fruits (Morton 1978). It produces bright red berries that are attractive to frugivores. Silvereyes, Figbirds, Currawongs and others are thought to disperse the seed. Fruiting occurs predominantly over Winter (Ensbey 2002). Evidence suggests this plant could provide an important alternative food source for desirable species, particularly as it fruits over Winter when food may be scarce. Extent of benefit to desirable species not documented | M | M |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | Consumption of foliage and/or fruits by horses & cattle can cause haemorrhages, intestinal compaction & fatal colic and horses resting beneath trees have developed dermatitis. Birds that feed excessively on the fruit have been known to become intoxicated and unable to fly, and massive bird kills are thought to be caused by heavy ingestion of the fruit (Morton 1978). The foliage and fruits are toxic to some mammals and birds, however, the affect on indigenous fauna is unknown. | M | ML |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | It is an important nectar and pollen source by the bee industry in Hawaii (Ferriter 1997). In Bermuda it is spread via the starling, Sturnus vulgaris, which consume its fruits (Mark & Lonsdale 2002). Domestic goats appear to eat Brazilian pepper without consequence (Meyer 2005). Provides food for minor pest species. | ML | MH |

| 18. Provides harbour? | In one study cotton mice and cotton rats were common in roadside stands (Ferriter 1997), so it is likely it could provide harbour for pest rodents in Australia. Florida panthers have been observed in Brazilian Pepper stands (Ferriter 1997), and with its ability to form large dense thickets, it has the capacity to provide harbour for rabbits, feral cats or foxes. However, no information was documented. | M | M |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | It forms around water holes, shading out all pasture (NCWAC 2001). Consumption of foliage by horse & cattle can cause haemorrhages, intestinal compaction & fatal colic. (Ferriter 1997). It has the potential to reduce pasture carrying capacity, limit stock access to water and cause stock fatalities, which could lead to reduction in yield >5%. | MH | M |

| 20. Impact quality? | ‘Grazing animals such as horses and cattle, are susceptible to its toxic effects, and ingestion of leaves and /or fruits has been known to be fatal (Ferriter 1997). Toxic affects may impact on stock health but there is no information to suggest it would impact directly on quality of agricultural produce. | L | M |

| 21. Affect land value? | It is declared a W2 noxious weed in NSW and a W3 weed in QLD. Its ability to form large, dense thickets, reduce pasture carrying capacity and its toxicity to grazing animals may lead to a minor decrease in land value of <10 % in grazing situations. | M | L |

| 22. Change land use? | Its capacity to form large dense nearly monotypic stands (Ferriter 1997) is likely to affect the visual appeal of the land. There is no information documented to suggest it would cause a change in the priority of land use. | ML | MH |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | It forms dense woody barricades that interfere with stock watering and mustering (NCWAC 2001). Minor increase in time and labour to harvest stock. | M | MH |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | It is a host of witches broom disease in citrus (Ensbey 2002), a host of mango bacterial black spot (Pruvost, Couteau & Luisetti 1992) and a host of olive fruit fly. (Athar 2005). Host of major diseases and pests of important agricultural produce. | H | MH |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | The germination period ranges from November to April with the highest activity occurring during January-February (Ferriter 1997). Seeds are thought to retain their viability during the wet season floods and germinate when water levels drop late in the year (Ferriter 1997). Natural seasonal disturbances appear to be required for germination. | MH | MH |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | It can survive under the dense shade of mature stands (Ferriter 1997). It has formed an understorey within mature stands of Swamp Oak (NSW agric.). Evidence suggests it can establish under moderate canopy cover. | MH | MH |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | ‘A well-known invader of disturbed sites, this species also colonises undisturbed native plant communities, including pinelands, hammocks and mangrove coastal areas…’ (Wheeler, Massey and Endries 2001). Establishes in disturbed areas but also intact or only minor disturbed natural ecosystems. | MH | MH |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Evergreen often multi-stemmed shrub or small tree generally 3-7 m or more (Ferriter 1997). Lifeform: Other. | L | MH |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | ‘Extracts of S. terebinthifolius negatively affected the germination and growth of two native plants commonly found in south Florida’s natural areas, Bromus alba & Rivinia humili (Morgan & Overhol 2005). ‘Numerous publications mention the plants allelopathic affects, yet as far as we are aware only one minor study has been conducted’ (Morgan & Overhol 2005). There is evidence to suggest this plant possesses allelopathic properties but due to limited research the impact of these properties is uncertain. | M | M |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | This species contains poisonous resins and is a relative of the Rhus tree and poison ivy. It is rarely eaten by livestock and reported toxic to other mammals and birds (NCWAC 2001). The fruits are consumed and dispersed by some birds and mammals (Ferriter 1997). Goats can consume the leaves without apparent toxic affects (Meyer 2005). Other than this there is very little evidence of foliar feeding or negative impacts of herbivory on the plant. | H | MH |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Seedlings can grow quickly. Seedlings reached a mean height of 4.6 m after 20 months (Meyer 2005) ‘…their rates of growth are among the highest ie. 0.3- 0.5 m per year’ (Ferriter 1997). It out-competes and replaces native grasses, ground covers and shrubs (Ensbey 2002). Rapid Growth Rate. | H | MH |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Although sensitive to freezing, it resprouts after frost damage (Meyer 2005). Plants quickly regrow from the base following fire (Ensbey 2002). Spreads rapidly on waterlogged or poorly drained soils (Ensbey 2002) and can grow in areas inundated for up to 3 - 6 months (Ferriter 1997). It is documented as being drought resistant, (Weber 2003) and seedlings are more drought tolerant than those of Schinus molle (Meyer 2005), which is also considered a drought resistant plant (Weber 2003). Highly tolerant of fire, drought and water logging, and moderately tolerant of frost. | H | MH |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | Root suckers form and can develop into new individuals (Ferriter 1997). Reproduces by seed (Ensbey 2002). Both vegetative & sexual reproduction. | H | MH |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | In one study, the total seed count collected from 40 inflorescences on a number of plants was 10,415 (Meyer 2005). Photos of specimens indicate that 40 inflorescences could commonly be found on a single tree. Above 2000 seeds. | H | MH |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | ‘Seeds are generally not viable 5 months following dispersal’ (Ferriter 1997). ‘…with no seeds surviving for 9 months’ (Panetta & McKee 1997). Seeds survive less than 5 years. | L | H |

| 12. Reproductive period? | ‘Some trees can live for 35 years’ (CAIP) Forms dense stand that are ‘self-maintaining’ (Ferriter 1997). Mature plant likely to produce propagules for 10 years or more and evidence that it forms ‘self sustaining’ monocultures. | H | MH |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | Plants are reported to set seed in less than 2 years in south-east Queensland (NCWAC 2001). Two-year old plants will produce seeds (Mack & Lonsdale 2002). Produces propagules between 1-2 years after germination. | MH | MH |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Avian dispersal agents include mockingbirds, cedar waxwings, catbirds and particularly robins. Raccoons are also known to disperse seeds. (Ferriter 1997). Silvereyes, Figbirds, Currawongs and others are thought to disperse the seed’ (Ensbey 2002). ‘…silvereyes have been observed feeding on fruits of S. terebinthifolius in the field, as have figbirds.’ (Panetta & McKee 1997). Birds are major dispersers of seed. | H | H |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | In one study, defecation of seeds by silvereyes ceased ~30 minutes after the fruits were withdrawn from feeding (Panetta & McKee 1997). In 30 minutes it is likely that birds could travel a significant distance. ‘The tendency for silvereyes to spend little time at a fruiting plant should increase their efficiency as dispersers’ (Panetta & McKee 1997). Larger birds such as Currawongs (Ensbey 2002) are also thought to disperse seed and would likely travel larger distances. Few propagules will disperse greater than one kilometre but many will reach 200 m or more. | MH | MH |

References

Athar, M 2005, ‘Infestation of olive fruit fly, Bactrocera oleae, in California and taxonomy of its host trees’, Agriculturae Conspectus Scientificus, vol. 70, no. 4, pp. 135-138.

Brooks, K 2001, ‘Managing weeds in Bushland - Woody Weed Control: Brazilian (Japanese Pepper) and other weeds’, Environmental Weeds Action Network (EWAN), http://members.iinet.net.au/~ewan/

Csurches, S & Edwards, R 1998, Potential Environmental Weeds in Australia, Biodiversity Group, Environment Australia, Canberra, viewed: 16 November 2006, http://www.deh.gov.au/biodiversity/invasive/publications/weeds-potential/index.html

Ensbey, R 2002, ‘Broad-leaf pepper tree: identification and control’, Agnote, DPI 426 (NSW Agriculture, Grafton, http://www.agric.nsw.gov.au).

Ewe, S 2001, Ecophysiology of Schinus terebinthifolius contrasted with native species in two South Florida ecosystems, Southeast Environmental Research Centre, Florida International University, Florida.

Ewel, JJ, Ojima, DS, Karl, DA & DeBusk, WF 1982, Schinus in Successional Ecosystems of Everglades National Park. South Florida Research Centre Report T-676, Everglades National Park, Florida.

Ferriter, A (ed.) 1997, Brazilian Pepper Management Plan for Florida, Brazilian Pepper Taskforce Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council, Florida, http://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/schinus.html

Centre for Aquatic and Invasive Plants (CAIP), 2005, Centre for Aquatic and Invasive Plants, Institute of Food & Agricultural Science (IFAS), University of Florida, viewed: 28 November 2006, http://aquat1.ifas.ufl.edu/schinus.html

Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) 2006, Global invasive species database, viewed 2006, http://www.issg.org/database/welcome/, viewed: 16 November 06

Mack, RN & Lonsdale, WM, ‘Eradicating invasive plants: Hard-won Lessons for islands’, in Turning the tide: the eradication of invasive species, eds. CR Veitch & MN Clout, IUCN SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK.

Meyer, R 2005, Schinus terebinthifolius, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fires Sciences Laboratory, http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Morgan, EC & Overholt, WA 2005, ‘Potential allelopathic effects of Brazilian pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi, Anacardiaceae) aqueous extract on germination and growth of selected Florida native plants’, Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society, vol. 132, no. 1, pp. 11-15.

Morton, JF 1978, ‘Brazilian Pepper- Its impact on people, animals and the environment’, Economic Botany, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 353-359.

North Coast Weeds Advisory Committee (NCWAC) 2001, Regional Weed Management Plan: Broad Leaf Pepper Tree- Schinus terebinthifolius’, North Coast Weeds Advisory Committee, Bellingen, NSW, http://www.northcoastweeds.org.au/weedmgmtplans.htm

Panetta, FD & McKee, J 1997, ‘Recruitment of the invasive ornamental, Schinus terebinthifolius, is dependant upon frugivores’, Australian Journal of Ecology, vol. 22, pp. 432-438.

Pruvost, 0, Couteau, A & Luisetti, J 1992, ‘Pepper Tree (Schinus terebinthifolius Raddi), a new host for Xanthomonas campestris pv. mangiferaeindicae’, Journal of Phytopathology, vol. 135, no. 4, pp. 289-298.

Weber, E. 2003, Invasive plant species of the world: a reference guide to environmental weeds, CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

Wheeler, GS, Massey, LM & Endries, M 2001, ‘The Brazilian Pepper Tree Drupe Feeder Megastigmus transvaalensis (Hymenoptera: Torymidae): Florida Distribution and Impact’, Biological Control, vol. 22, pp. 139-148.

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) 2006, Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, viewed: 21 November 06, http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/

Calflora: Information on California plants for education, research and conservation. [web application]. 2006. Berkeley, California: The Calflora Database [a non-profit organization] viewed: 16 November 2006, http://www.calflora.org/.

Department of Environment & Conservation 2006, Florabase: The Western Australian Flora, Department of Environment & Conservation, Government of Western Australia, viewed: 16 November 2006, http://www.naturebase.net/florabase/index.html

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2006, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed: 21 November 2006, http://www.gbif.org/

Henderson, L 1995, Plant Invaders of Southern Africa, Plant Protection Research Institute, Agricultural Research Council, Pretoria.

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.