Tatarian honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica)

Present distribution

|  This weed is not known to be naturalised in Victoria | ||||

| Habitat: Reported to invade woodland, forest, riparian forest and grassland (Borgmann & Rodewald 2005; Brudvig & Evans 2006; Weber 2003). Has also been reported to occur in a Red Pine Plantation (Norby & Kozlowski 1980). | |||||

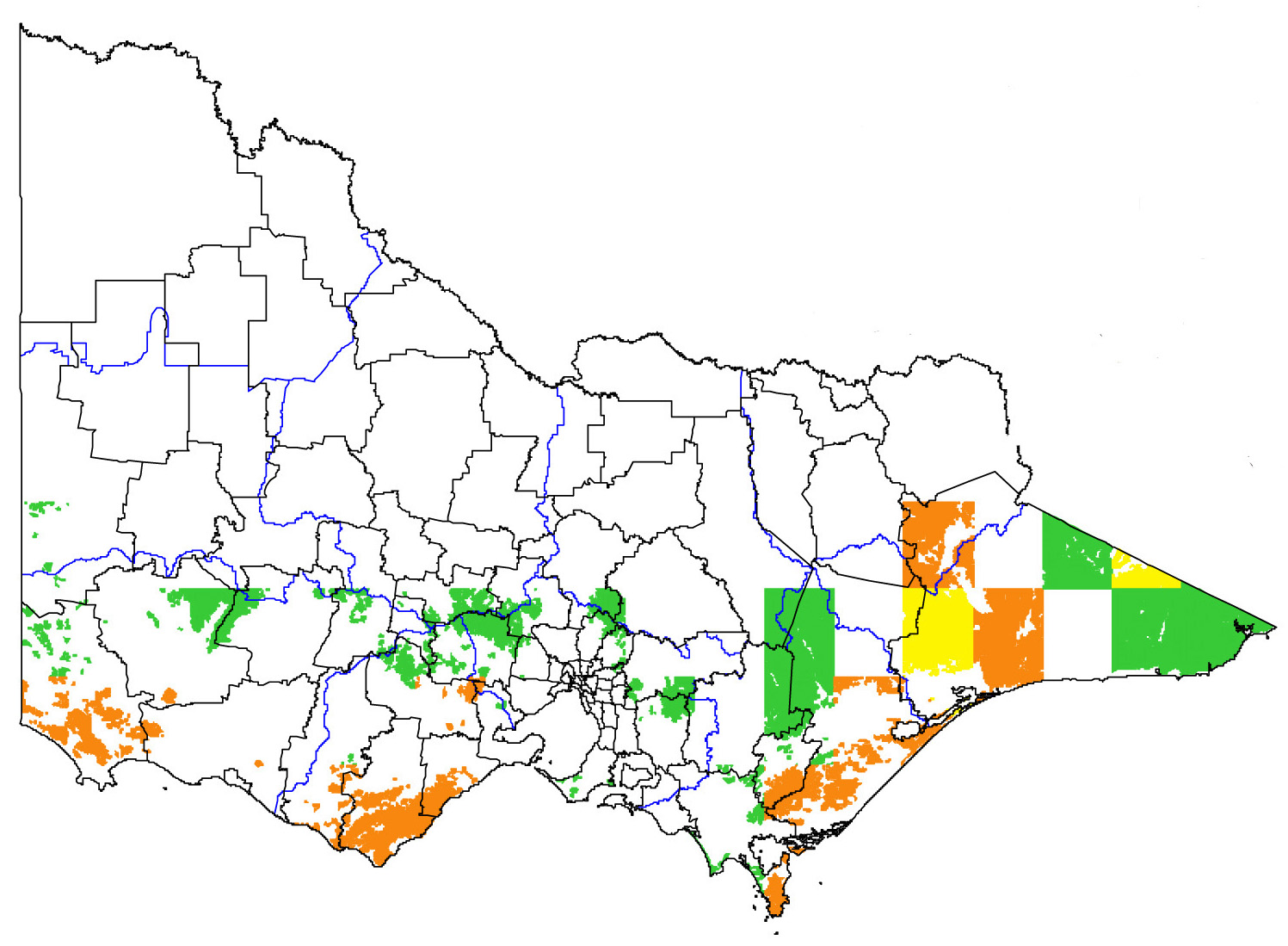

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Forest private plantation; forest public plantation Broad vegetation types Coastal grassy woodland; lowland forest; box ironbark forest; inland slopes woodland; sedge rich woodland; dry foothills forest; moist foothills forest; montane dry woodland; montane moist forest; sub-alpine woodland; grassland; plains grassy woodland; valley grassy forest; herb-rich woodland; sub-alpine grassy woodland; montane grassy woodland; riverine grassy woodland; riparian forest; rainshadow woodland; wimmera / mallee woodland Colours indicate possibility of Lonicera tatarica infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Can from dense impenetrable stands (Drummond 2005; Weber 2003). Therefore for a shrub species significant works would be required to control the species to maintain access. | h | mh |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | Ornamental species therefore could alter the aesthetics. | ml | l |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Fruits of other shrubby honeysuckle species have been reported to be toxic, but they are also very bitter and around 30 would need to be eaten before problems occurred (Luken & Thieret 1995). | ml | m |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | Ornamental species therefore could alter the aesthetics. | ml | l |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Not reported in flowing water. | l | m |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Terrestrial species. | l | m |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | The similar shrub honeysuckle L. maackii has been used for soil stabilisation, and some cultivars are still recommended (Luken & Thieret 1996). Therefore it is presumed that L. morrowii would have a low probability of allowing large-scale soil movement. | l | m |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | Reported to develop a shrub layer in closed canopy forest (Woods 1993). Therefore potentially increasing biomass. | l | mh |

| 9. Change fire regime? | Specific relationship with fire unknown, however alteration of biomass in the shrub layer and therefore elevated fuels could alter fire intensity. | m | l |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC= Dry Valley Forest (V); CMA= East Gippsland; Bioreg= East Gippsland Uplands; H CLIMATE potential. Lonicera tatarica is able to form dense stands, which shade out the lower strata, displacing species and impacting upon forest regeneration (Weber 2003). Therefore causing major displacement. | mh | mh |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC= Grassy Woodland (D); CMA= East Gippsland; Bioreg= East Gippsland Uplands; H CLIMATE potential. Lonicera tatarica is able to form dense stands, which shade out the lower strata, displacing species and impacting upon forest regeneration (Weber 2003). Therefore causing major displacement. | mh | mh |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC= Grassy Dry Forest (LC); CMA= East Gippsland; Bioreg= East Gippsland Uplands; H CLIMATE potential. Lonicera tatarica is able to form dense stands, which shade out the lower strata, displacing species and impacting upon forest regeneration (Weber 2003). Therefore causing major displacement. | mh | mh |

| 11. Impact on structure? | Lonicera tatarica is able to form dense stands, which shade out the lower strata, displacing species and impacting upon forest regerneration (Weber 2003). Increasing cover of L. tatarica has been associated with decreasing richness of herbs and tree seedling density and therefore impacting upon canopy regeneration (Woods 1993). Therefore impacting upon the lower strata as well as the canopy to a lesser extent. | mh | h |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | No specific evidence on threatened species. | mh | l |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | No specific evidence on threatened species. | mh | l |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | Alteration of habitat could have negative impacts on the fauna. | m | l |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | Fruit readily eaten by bird species in Maine (Drummond 2005). | mh | mh |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | None reported. | l | m |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | Produces a lot of nectar accessible to bees (Petkov 1975). The fruit is eaten by bird species (Drummond 2005). | ml | h |

| 18. Provides harbor? | Forms dense thickets that could be shelter for many different species, if only temporarily. No evidence of the species sheltering pest fauna. | m | l |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | It has been shown that through its allelopathic properties to reduce the growth rate of red pine seedlings, to the extent that after a seven week experiment the treated seedlings had a dry weight of 46% of the control (Norby & Kozlowski 1980). Unknown how this could impact the yield of a plantation of the lifetime of the tree. | m | m |

| 20. Impact quality? | May have some impact on the quality of timber, however there is no evidence to that extent. | m | l |

| 21. Affect land value? | There is not evidence to support this. | l | m |

| 22. Change land use? | May alter some forestry practises, however there is not evidence to support this. | m | l |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | May result in additional maintenance of forestry plots. | m | l |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | An alternate food plant for the cherry fruit-fly (Rhagoletis cerasi) (Thiem 1932). | m | h |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | High germination yields have been reported if seeds are sown early in spring (Cram 1982). Germination of the similar shrubby honeysuckle L. maackii can occur year round (Luken & Thieret 1996). The majority of seeds may germinate if sown in spring which would replicate natural processes however this doesn’t exclude seeds from germinating at other time of the year and with the similar species capabile of this it is presumed that this species may also be capable of year round germination. | h | m |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | Able to invade closed canopies forest (Woods 1993). | mh | h |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Can invade intact riparian vegetation (Borgmann & Rodewald 2005). | mh | h |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Shrub (Brudvig & Evans 2006). Therefore other. | l | h |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | Red pine seedlings treated with an extract from L.tatarica had a reduced growth rate under experimental conditions (Norby & Kozlowski 1980). | ml | h |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Resistant to deer (Dave’s Garden 2007). Therefore probably avoided by browsing species. | mh | m |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Reported to grow vigorously (Weber 2003). Found to have a similar growth rate with Quercus alba under experimental conditions, however L. tatarica is also aggressively invading habitats within this species native range (Brudvig & Evans 2006). Therefore this species is competetive. | mh | h |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Can tolerate temperatures to -34C (Dave’s Garden 2007). Therefore frost tolerant. Salt tolerance disputed, Klincsek & Totok (1978) reports the species tolerant while Tinus & Murphy (1984) report it as sensitive. Unknown response to waterlogging other honeysuckle species have been found to be tolerant of drought and fire. | m | m |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | Capable of self and out crossing (Gunatilleke & Gunatilleke 1988). | ml | h |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | Unknown specifically, presumed to be similar to other shrubby honeysuckle species like L. maackii. | mh | m |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | Seeds stored in sealed containers at 1-3C for 15 years had a germination rate of 84%, while none of those stored at 16-29C germinated. While seeds stored in an open bag for 6 years at 1-3C only 11% germinated and again non stored at 16-29C germinated. However there is some dispute as the seeds were not tested for viability and therefore it can not be said conclusively that those seeds that didn’t geminate were not viable (Hidayati, Baskin & Baskin 2002). If the seeds that didn’t germinate were not viable, these test could indicate that viability under natural conditions (Those deemed most like natural conditions being stored in an open container at temperatures ranging from 16-29C) was within 6 years. | l | m |

| 12. Reproductive period? | Unknown however the reproductive period of the similar shrub honeysuckle L. maackii was calculated to potentially be more than 10 years. As it can live to 17 years and reaches maturity between 3 and 5 years (Deering & Vankat 1999; Luken & Thieret 1995). | h | m |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | Not known however the similar shrubby honeysuckle L. maackii when grown from seed, will flower in 3-5 years (Luken & Thieret 1995). | ml | m |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Birds consume the fruit and disperse the seeds (Drummond 2005). | h | h |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | Birds can disperse seeds more than 1km (Spennemann & Allen 2000). | h | mh |

References

Borgmann K.L. & Rodewald A.D., 2005, Forest restoration in urbanizing landscapes: Interactions between land uses and exotic shrubs. Restoration Ecology. 13: 334-340.

Brudvig L.A. & Evans C.W., 2006, Competitive effects of native and exotic shrubs on Quercus alba seedlings. Northeastern Naturalist. 13: 259-268

Cram W.H., 1982, Seed germination of Elder (Sambucus pubens) and Honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica). HortScience. 17: 618-619.

Dave’s Garden: Dave’s Garden “For Gardeners… By Gardeners”. viewed 5 Feb 2007, http://davesgarden.com/

Drummond B.A., 2005, The selection of native and invasive plants by frugivorous birds in Maine. Northeastern Naturalist. 12: 33-44.

Gunatilleke I.A.U.N. & Gunatilleke C.V.S., 1988, Some observations on the reproductive biology of three species of Lonicera L. (Caprifoliaceae). Ceylon Journal of Science. 18: 66-76.

Hidayati S.N., Baskin J.M. & Baskin C.C., 2002, Effects of dry storage on germination and survivorship of seeds of four Lonicera species (Caprifoliaceae). Seed Science & Technology. 30: 137-148.

Klincsek P. & Totok K., 1978, Response of trees and shrubs to salting roads in winter. Kertgazdasag. 10: 39-50.

Luken J.O. & Thieret J.W., 1996, Amur honeysuckle, its fall from grace. Bioscience. 46: 18-24.

Norby R.J. & Kozlowski T.T., 1980, Allelopathic potential of ground cover species on Pinus resinosa seedlings. Plant and Soil. 57: 363-374.

Petkov V., 1975, Determining the nectar-yielding capacity of Mahonia aquifolium, Lonicera tatarica, Simphoricarpus orbiculatus, Aesculus hippocastanum, Acer tataricum. Rastenievudni Nauki. 12: 157-163.

Thiem H., 1932, Lonicera tatrica and Berberis vulgaris as Food-plants of the Cherry Fruit-fly, R. cerasi. Nachrbl. deuts. 12: 41-43.

Tinus R.W. & Murphy P.M., 1984, Salt tolerance of 10 deciduous shrub and tree species. General Technical Report, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station,

USDA Forest Service. 44-49

Weber E. 2003, Invasive plant species of the world: a reference guide to environmental weeds, CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

Woods K.D., 1993, Effects of invasion by Lonicera tatarica L. on herbs and tree seedlings in four New England forests. The American Midland Naturalist. 130: 62-74

Global present distribution data references

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2007, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed 16 Jan 2007, http://www.gbif.org/

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) 2007, w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, viewed 15 Jan 2007, http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.