Smooth bedstraw (Galium mollugo)

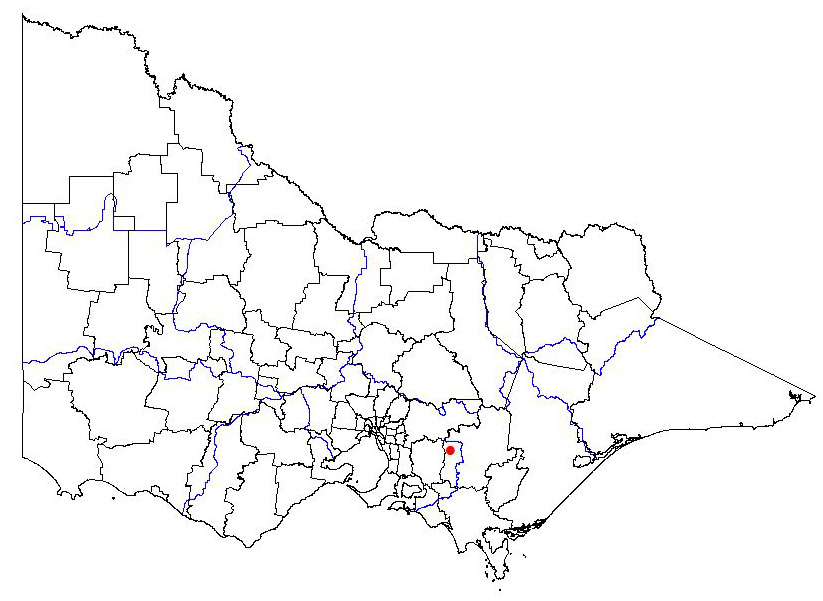

Present distribution

|  Map showing the present distribution of this weed. | ||||

| Habitat: Pastures and waste places, rarely cultivated land (Webb et al. 1988). Grows in mountainous regions of the Pyrenees in southern France; sometimes the dominant vegetation along river flats, but does not grow well in saline soils (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003), principally occurring in habitats including areas along railroads and roadsides, thickets, and woodland borders (Hilty 2010). Habitats include woodland, sunny edge, dappled shade, shady edge; is frost tolerant (Plants Future 1996−2008). G. mollugo has maximum shade tolerance (Hamilton and Bell 2004). Occurs at altitudes ranging between 100 and 1650 m; in pastures, meadows, the margins of water courses, woods, showing no edaphic preferences (Ortega-Olivencia and Devesa 2003). Prefers moist, cool conditions, but can tolerate drought (Seiter 2003). | |||||

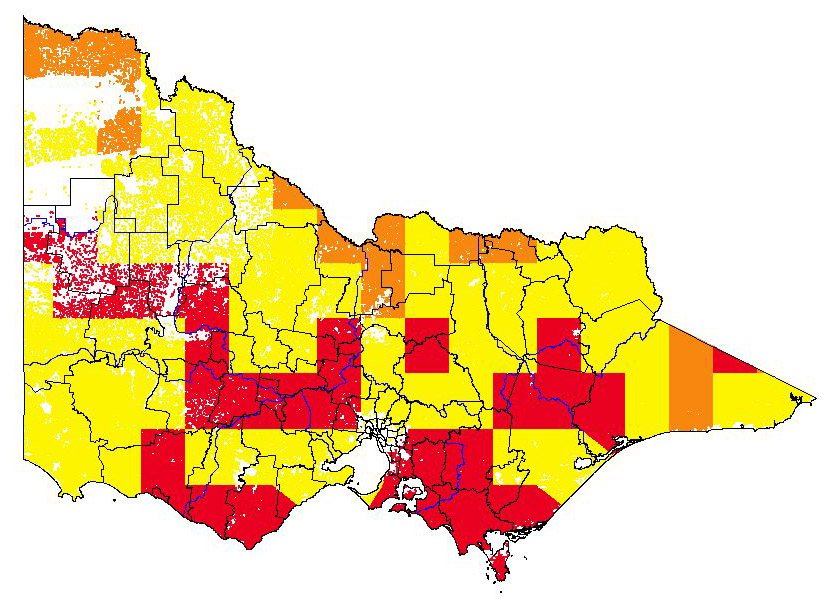

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Forestry; horticulture perennial; horticulture seasonal; pasture dryland; pasture irrigation Ecological Vegetation Divisions Grassy/heathy dry forest; lowland forest; foothills forest; forby forest; damp forest; riparian; wet forest; rainforest; high altitude shrubland/woodland; granitic hillslopes; western plains woodland; basalt grassland; alluvial plains grassland; semi-arid woodland; alluvial plains woodland; riverine woodland/forest Colours indicate possibility of Galium mollugo infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Sprawling perennial; stems to 30 cm long, longer amongst tall vegetation (Webb et al. 1988). The foliage of this plant lacks any stiff or clinging hairs (Hilty 2010). Individual plants 25−120 cm tall. Woody rhizomes are branching and articulate, spreading horizontally. Stems emerge from a crown-like clump 20−60 cm diameter. Sometimes the dominant vegetation along river flats. Vigorous, mature plants can extend over an area of 1 m or more in diameter (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Individual plants can grow 1 to 3 feet tall and spread to 3 feet or more in diameter (Seiter 2003). Occurs on margins of watercourses (Ortega-Olivencia and Devesa 2003). High nuisance value. People and/or vehicles access with difficulty. | MH | H |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | The foliage of this plant lacks any stiff or clinging hairs (Hilty 2010). A sprawling perennial (Webb et al. 1988); individual plants can grow 1 to 3 feet tall and spread to 3 feet or more in diameter (Seiter 2003); sometimes the dominant vegetation along river flats (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003) and margins of watercourses (Ortega-Olivencia and Devesa 2003). Some recreational activities affected. | MH | H |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Bedstraw contains a number of toxic compounds (Ottauquechee NRCD 2002). G. mollugo contains anthraquinone compounds that have systemic toxicity to mammals, and may result in skin irritation or sensitization (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). The foliage of this plant lacks any stiff or clinging hairs (Hilty 2010). Mildly toxic; may cause some physiological issues at certain times of the year. | ML | MH |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | A sprawling perennial (Webb et al. 1988); individual plants can grow 1 to 3 feet tall and spread to 3 feet or more in diameter (Seiter 2003); sometimes the dominant vegetation along river flats (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Moderate visual effect. | ML | H |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Vigorous, mature plants can extend over an area of 1 m or more in diameter; sometimes the dominant vegetation along river flats (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003) and margins of watercourses (Ortega-Olivencia and Devesa 2003), although principally terrestrial, occurring in habitats including areas along railroads and roadsides, thickets, woodland borders, and various waste places (Hilty 2010). Little or negligible effect on water flow. | L | H |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Sometimes the dominant vegetation along river flats (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003) and margins of watercourses (Ortega-Olivencia and Devesa 2003), although principally terrestrial, occurring in habitats including areas along railroads and roadsides, thickets, woodland borders, and various waste places (Hilty 2010). No noticeable effect on dissolved O2 or light levels. | L | H |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | Long-lived perennial; individual plants 25−120 cm tall with strong, much-branched taproot to 50 cm depth. Woody rhizomes are branching and articulate, spreading horizontally to produce new stems and roots at their nodes. The root system is dense. Stems emerge from a crown-like clump 20−60 cm diameter (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Principally terrestrial, occurring in habitats including areas along railroads and roadsides, thickets, woodland borders, and various waste places (Hilty 2010). Occurs in disturbed areas (Jepson 1995–2009). Considering the depth and density of the rhizomatous root system of this long-lived perennial, G. mollugo would possibly decrease rather than increase soil erosion. Low probability of large scale soil movement or decreases the probability of soil erosion. | L | H |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | In areas where G. mollugo sprawls or stems become longer amongst tall vegetation (Webb et al. 1988) or becomes matted and climbs over adjacent vegetation (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003), the overall biomass could possibly decrease. However, where G. mollugo occurs in pastures (Ortega-Olivencia and Devesa 2003; Ottauquechee 2002; Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003), forage crops (Seiter 2003), hayfields and waste areas (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003) it is likely to increase biomass. Biomass slightly decreased. | MH | H |

| 9. Change fire regime? | Although G. mollugo grows to 120 cm, the stems are slender and soft (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003), and therefore unlikely to increased fire risk. No specific mention in literature of change in fire frequency or intensity caused by G. mollugo. Small or negligible effect on fire risk. | L | L |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC = Riparian Shrubland (E); CMA = Goulburn Broken; Bioregion = Central Victorian Uplands; VH CLIMATE potential. In the absence of support from adjacent vegetation, G. mollugo has a tendency to sprawl, but stems become longer amongst tall vegetation (Webb et al. 1988) or otherwise the plant becomes matted and climbs over adjacent vegetation (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Very little displacement of any indigenous species. Sparse/ scattered infestations. | ML | MH |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC = Shrubby Foothill Forest (D); CMA = Corangamite; Bioregion = Warrnambool Plain; VH CLIMATE potential. In the absence of support from adjacent vegetation, G. mollugo has a tendency to sprawl, but stems become longer amongst tall vegetation (Webb et al. 1988) or otherwise the plant becomes matted and climbs over adjacent vegetation (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Very little displacement of any indigenous species. Sparse/ scattered infestations. | ML | MH |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC = Heathy Dry Forest (LC); CMA = East Gippsland; Bioregion = Highlands- Southern Fall; VH CLIMATE potential. In the absence of support from adjacent vegetation, G. mollugo has a tendency to sprawl, but stems become longer amongst tall vegetation (Webb et al. 1988) or otherwise the plant becomes matted and climbs over adjacent vegetation (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Very little displacement of any indigenous species. Sparse/ scattered infestations. | ML | MH |

| 11. Impact on structure? | In the absence of support from adjacent vegetation, G. mollugo has a tendency to sprawl, but stems become longer amongst tall vegetation (Webb et al. 1988) or otherwise the plant becomes matted and climbs over adjacent vegetation (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Minor effect on 20-60% of the floral strata. | ML | MH |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | Impact on threatened flora has not yet been determined. | MH | L |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | Impact on threatened flora has not yet been determined. | MH | L |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | Impact on threatened fauna has not yet been determined. | M | L |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | Livestock typically avoid G. mollugo (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003; Parakh and Schreiber 1960; Seiter 2003). Otherwise, little information is available about this species' relationship to birds and mammalian herbivores (Hilty 2010). Provides very little support to desirable species. | H | H |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | The foliage of this plant lacks any stiff or clinging hairs (Hilty 2010). Bedstraw contains a number of toxic compounds (Ottauquechee NRCD 2002). G. mollugo contains anthraquinone compounds that have systemic toxicity to mammals, and may result in skin irritation or sensitization (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Livestock typically avoid eating G. mollugo (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003; Parakh and Schreiber 1960; Seiter 2003). Toxic and/or causes allergies. | H | H |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | G. mollugo is recorded as being a food source for wild rabbits. Also known to be a host or secondary food source for various European plant pests (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). G. mollugo is attractive to parasitoids without providing an accessible food source (Wäckers 2004). The small amount of nectar in the flowers attracts various kinds of flies, including Soldier flies, Bee flies, Syrphid flies (which also feed on the pollen), Muscid flies, Crane flies, and Dung flies. It is possible that small bees also visit the flowers, but they are probably less common. The foliage of Galium spp. is eaten by the caterpillars of several moths (Hilty 2010). Germination of seeds from white-tailed deer faeces (Myers et al. 2004). Livestock typically avoid eating this plant (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003; Parakh and Schreiber 1960). Supplies food for serious pest, but at low levels. | H | H |

| 18. Provides harbour? | Occurs on margins of watercourses (Ortega-Olivencia and Devesa 2003). Sprawling perennial (Webb et al. 1988) with ascending or procumbent stems to 150 cm long (Jeanes 1999). Long-lived perennial; individual plants 25−120 cm tall; stems emerge from a crown-like clump 20−60 cm diameter; sometimes the dominant vegetation along river flats (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Individual plants can grow 0.35 to 1 m tall and spread to 1 m or more in diameter (Seiter 2003). Capacity to harbour rabbits or foxes at low densities or as overnight cover. | MH | H |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | Livestock typically avoid this plant, such that it becomes firmly established and highly competitive in pasture areas, displacing more palatable forage crops (Parakh and Schreiber 1960). Galium mollugo has become a problem weed in many forage crops. It can significantly reduce yields of forage grasses such as timothy or orchard grass as well as forage legumes such as red clover and yellow sweet clover (Seiter 2003). Highly competitive in pasture areas where 10−80% of land area may become infested, sometimes [for timothy] eliminating 80−90% of the grass sword (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Serious impacts on quantity. | H | H |

| 20. Impact quality? | Seeds get dispersed via water, in the fleece of sheep and as a contaminant of crop seeds (Seiter 2003). Quality of pasture is potentially impacted because livestock typically avoid this plant, allowing it to displace more palatable forage crops. Highly competitive in pasture areas where 10−80% of land area may become infested (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Serious impacts on quantity (e.g. >20% reduction. | H | H |

| 21. Affect land value? | This weed proliferates, even in established forage crop stands. Once established, smooth bedstraw is a tough weed to manage (Seiter 2003). G. mollugo is considered an effective invasive species because of its ability to colonise and proliferate in areas such as established meadows where most invaders do not survive. Livestock typically avoid this plant, such that it becomes firmly established and highly competitive in pasture areas where 10−80% of land area may become infested, sometimes [for timothy] eliminating 80−90% of the grass sword (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Major significance > 10%. | H | H |

| 22. Change land use? | G. mollugo is considered an effective invasive species because of its ability to colonise and proliferate in areas such as established meadows where most invaders do not survive. Livestock typically avoid this plant, such that it becomes firmly established and highly competitive in pasture areas where 10−80% of land area may become infested, sometimes [for timothy] eliminating 80−90% of the grass sword (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Livestock typically avoid this plant, such that it becomes firmly established and highly competitive in pasture areas, displacing more palatable forage crops (Parakh and Schreiber 1960). Galium mollugo has become a problem weed in many forage crops. It can significantly reduce yields of forage grasses such as timothy or orchard grass as well as forage legumes such as red clover and yellow sweet clover. Once established, smooth bedstraw is a tough weed to manage (Seiter 2003). Downgrading of the priority of landuse to one with less agricultural return. | MH | H |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | Seeds are found in the fleece of sheep and as a contaminant of crop seeds (Seiter 2003). This weed proliferates even in established forage crop stands (Seiter 2003), and is highly competitive in pasture areas where 10−80% of land area may become infested (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Minor increase in cost of harvesting. | M | H |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | G. mollugo is known to be a host or secondary food source for various European plant pests, including Pear aphids, cherry aphids, and various species of the genus Formica which transmit the trematode Dicrocoelium lanceatum to grazing livestock (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). G. mollugo is attractive to parasitoids without providing an accessible food source (Wäckers 2004). The small amount of nectar in the flowers attracts various kinds of flies, including Soldier flies, Bee flies, Syrphid flies (which also feed on the pollen), Muscid flies, Crane flies, and Dung flies. It is possible that small bees also visit the flowers, but they are probably less common. The foliage of Galium spp. is eaten by the caterpillars of several moths (Hilty 2010). Host to major and severe disease or pest of important agricultural produce. | M | H |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | G. mollugo reproduces vegetatively and by seed; woody rhizomes spread horizontally, producing new stems and roots at the nodes (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). The closely related G. aparine, produces two populations per year. The ability of a winter populations to produce large seeds that germinate early and have two germination peaks per year could make populations of G. aparine a serious problem in cropping systems (Mennan and Ngouajio 2006). For Galium tricornutum in Australia, germination was inhibited by light; when seeds were transferred to complete darkness they germinated readily. Germination was also promoted by cold-stratification at 5° C (Chauhan et al. 2006). Opportunistic germinator, can germinate or set root at any time whenever water is available. | H | H |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | This plant can be found growing in light shade to full sun in more or less mesic conditions. It becomes larger in fertile loam, but can grow in other kinds of soil (Hilty 2010). G. mollugo has maximum shade tolerance (Hamilton and Bell 2004). This plant prefers light (sandy), medium (loamy) and heavy (clay) soils; acid, neutral and basic (alkaline) soils; can grow in dry or moist soil; semi-shade (light woodland) (Plants Future 1996−2008). Can tolerate low fertility, low pH, but also thrives in well-managed fields because of its adaptation to a wide range of environmental conditions (Seiter 2003). Can establish under moderate canopy/litter cover. | MH | MH |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Habitats include areas along railroads and roadsides, thickets, woodland borders, and various waste places. Hedge Bedstraw is currently found in areas with a history of disturbance (Hilty 2010). G. mollugo is found in pastures, meadows, the margins of water courses, walls, hedges, and holm oak, chestnut, and beech woods, showing no edaphic preferences (Ortega-Olivencia and Devesa 2003). This weed proliferates even in established forage crop stands (Seiter 2003). G. mollugo is considered an effective invasive species because of its ability to colonise and proliferate in areas such as established meadows where most invaders do not survive (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Establishes in relatively intact or only minor disturbed natural ecosystems, or in well established pastures. | H | H |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Sprawling perennial with stout rootstock; stems to 30 cm long, longer amongst tall vegetation (Webb et al. 1988). Perennial with ascending or procumbent stems to 150 cm long (Jeanes 1999). Long-lived perennial; individual plants 25−120 cm tall with strong, much-branched taproot to 50 cm depth. Woody rhizomes are branching and articulate, spreading horizontally to produce new stems and roots at their nodes. The root system is dense. Stems emerge from a crown-like clump 20−60 cm diameter (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Individual plants can grow 0.35 to 1 m tall and spread to 1 m or more in diameter (Seiter 2003). Geophyte, climber or creeper. | ML | H |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | Galium mollugo in dilutions of 1:1 to 1:100 of plant material to water inhibited germination of wheat and radish, and dilutions of 1:10 to 1:500 retarded growth of seedlings of sunflower by 10 to 100%. Development of onion bulbs and roots was also markedly inhibited by similar extracts (Rice 1984). Bedstraw species, including G. mollugo, contain many compounds including mollugin, some of which have allelopathic, fungalistic or repellent effects (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). G. mollugo contains several allelochemicals, and express allelopathic inhibitory activity on onion, radish, sunflower and wheat (Qasem and Foy 2001). Major allelopathic properties inhibiting all other plants | H | H |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Livestock typically avoid this plant, such that it becomes firmly established and highly competitive in pasture areas, displacing more palatable forage crops (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). In pastures, animals may graze Smooth Bedstraw if is young and tender, but once Bedstraw matures, it will be less palatable (Ottauquechee NRCD 2002). Livestock usually prefer forage grasses over bedstraw. Consequently, grazing reduces the bedstraw’s competition, which allows it to spread. If mowed soon after the first flowering, plants may flower a second time in August (Seiter 2003). Bedstraw in pastures is usually avoided by grazing animals, thus enabling it to reproduce and disseminate seed (Parakh and Schreiber 1960) Favoured by heavy grazing pressure as not preferred food of grazing animals. | H | H |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Under favourable conditions, growth and clonal expansion can occur rapidly. Stems are at first erect but soon become matted and climb over adjacent vegetation (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Perennial plant growing to 1.2 m by 0.6 m at a medium rate (Plants Future 1996−2008). Moderately rapid growth that will equal competitive species of the same life form. | MH | MH |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | G. mollugo does not grow well in saline soils; low germination under a range of salinity concentrations; field trials showed none of the seedlings emerging in plots with higher salinities survived the first year. Tolerates drought. Grows in central New York with mean annual temperature of 8.5°C (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Galium is frost hardy (Page and Olds 1998). G. mollugo is found growing at the margins of water courses (Ortega-Olivencia and Devesa 2003). Highly resistant to at least two of drought, frost, fire, waterlogging or salinity; not susceptible to more than one. | H | MH |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | G. mollugo reproduces vegetatively and by seed; woody rhizomes spread horizontally, producing new stems and roots at the nodes. Introgressive hybridization between G. mollugo and G. verum can result in aggressive weedy plants (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Smooth bedstraw produces many seeds and, once established, can then spread from rhizomes (Seiter 2003). The root system is rhizomatous and can produce numerous vegetative offsets (Hilty 2010). The plant is self-fertile (Plants Future 1996−2008). Both sexual and vegetative reproduction. | H | H |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | Due to the large number of decumbent stems, plants can often spread over an area of 1 m or more. “… one of 18 stems from a single plant produced 2283 seeds.” (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Smooth bedstraw is a prolific seed producer (Ottauquechee NRCD 2002). Smooth Bedstraw plants produce many seeds, which remain viable for about a year (Seiter 2003). The root system is rhizomatous and can produce numerous vegetative offsets (Hilty 2010). Greater than 2000. | H | MH |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | Smooth Bedstraw plants produce many seeds, which remain viable for about a year (Seiter 2003). G. mollugo seeds possess little or no innate dormancy, and do not persist in the soil for more than a year (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Greater than 25% of seeds survive 5 years OR reproduces vegetatively. | L | H |

| 12. Reproductive period? | G. mollugo is a long-lived perennial that reproduces vegetatively and by seed; woody rhizomes spread horizontally, producing new stems and roots at the nodes (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Similar to many other Galium species, G. mollugo is a long-lived perennial (Parakh and Schreiber 1960). Mature plant produces viable propagules for 3−10 years. | MH | H |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | Under favourable conditions, growth and clonal expansion can occur rapidly (Mersereau and DiTommaso 2003). Produces propagules between 1−2 years after germination or vegetative propagules become separate individuals after 1−2 years. | MH | H |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Smooth bedstraw can be spread quickly by animals and equipment (Ottauquechee NRCD 2002). Seeds get dispersed via birds, sheep, water, and contaminated crop seeds (Seiter 2003). Seeds of G. mollugo germinated from fresh dung samples of cattle, donkey, horse, sheep and rabbit (Hoffmann et al. 2005). Seeds of G. mollugo have germinated from the faeces of white-tailed deer (Myers et al. 2004). Seeds dispersed by birds or is readily eaten by highly mobile animals. | H | H |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | Smooth bedstraw can be spread quickly by animals and equipment (Ottauquechee NRCD 2002). Seeds get dispersed via birds, sheep, water, and contaminated crop seeds (Seiter 2003). Seeds of G. mollugo germinated from fresh dung samples of cattle, donkey, horse, sheep and rabbit (Hoffmann et al. 2005). Very likely that at least one propagule will disperse greater than one kilometre. | H | H |

References

Chauhan BS, Gurjeet Gill G and Preston C. (2006) Factors affecting seed germination of threehorn bedstraw (Galium tricornutum) in Australia. Weed Science 54(3):471−477. Available at http://pinnacle.allenpress.com/doi/abs/10.1614/WS-05-176R1.1 (verified April 2010).

Hamilton SW and Bell NA (2004) Annual and Perennial Flower Shade Gardening in Tennessee. Department of Ornamental Horticulture and Landscape Design, University of Tennessee. Available at http://www.utextension.utk.edu/publications/pbfiles/pb1585.pdf (verified April 2010).

Hilty J. (2010) Illinois Wildflowers, Weedy Wildflowers of Illinois, Galium mollugo page. Available at http://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/weeds/plants/hedge_bedstraw.htm (verified April 2010).

Hoffmann M, Cosyns E and Lamoot I. (2005) Large herbivores in coastal dune management: do grazers do what they are supposed to do? In Proceedings ‘Dunes and Estuaries 2005’ – International Conference on Nature Restoration Practices in European Coastal Habitats. Herrier J.-L., J. Mees, A. Salman, J. Seys, H. Van Nieuwenhuyse and I. Dobbelaere (Eds) p. 249−267. Available at https://biblio.ugent.be/input/download?func=downloadFile&fileOId=581252&recordOId=381376 (verified April 2010).

Jeanes JA. (1999) Rubiaceae, Galium. In. Walsh NG and Entwistle TJ. Flora of Victoria. Vol. IV. pp. 618–619.

Jepson (1995–2009) Jepson Flora Project, Jepson Interchange, Galium mollugo page. Available at http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/cgi-bin/get_JM_treatment.pl?6927,6934,6994 (verified 12 May 2010).

Mennan H and Ngouajio M. (2006) Seasonal cycles in germination and seedling emergence of summer and winter populations of catchweed bedstraw (Galium aparine) and wild mustard (Brassica kaber). Weed Science 54(1): 114−120. Available at http://pinnacle.allenpress.com/doi/abs/10.1614/WS-05-107R1.1 (verified April 2010).

Mersereau D and DiTommaso A. (2003) The biology of Canadian weeds. 121. Galium mollugo L. Canadian Journal of Plant Science 83: 453–466. Available at

http://www.css.cornell.edu/weedeco/Galium%20mollugo%20CJPl.Sci.pdf (verified 18 May 2010).

Myers JA, Vellend M, Gardescu S and Marks PL. (2004) Seed dispersal by white-tailed deer: implications for long-distance dispersal, invasion, and migration of plants in eastern North America. Oecologia 139: 35–44. Available at http://www.nceas.ucsb.edu/~vellend/Myers_Vellend_etal_Oecologia_2004.pdf (verified April 2010).

Ortega-Olivencia A and Devesa JA (2003) Two new species of Galium (Rubiaceae) from the Iberian Peninsula. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 143: 177−187. Available at http://852224059504902715-a-1802744773732722657-s-sites.googlegroups.com/site/digitdevesa/AE002684OCR.pdf?attachauth=ANoY7cov6-DTWNTAt15oIxgb8CDWiVvrN80o4OYiunyDLYSrwoJOsS2eyaI0ZNJhHqeoDHUtOJcttj4oiBpIeaOT42DREwBDtfa61N3pU5eDMwBDFHw1yhU9e4N6W5r2oq9GPITZNiqUdlN3ifWCIgyxrQAU_ufBH2Zw87xFpmgJnKM193zouP3Fy_0XYR--M0OwtHCecit&attredirects=0 (verified April 2010).

Ottauquechee NRCD (2002) Ottauquechee Natural Resources Conservation District, Galium mollugo (Smooth Bedstraw) Fact Sheet. Available at

http://vacd.org/onrcd/Bedstraw_factsheet.pdf (verified April 2010).

Page S and Olds M. (1998) Botanica: The illustrated A−Z of over 10,000 garden plants. Galium section. Random House, Sydney.

Plants Future (1996−2008) Plants for a Future. Galium mollugo page. Available at http://www.pfaf.org/database/plants.php?Galium+mollugo (verified April 2010).

Parakh JS and Schreiber MM. (1960) Control of Bedstraw (Galium mollugo) with Alpha-Phenoxypropionic Acid Derivatives. Weeds 8(1): 94−106.

Quasem JR and Foy CL. (2001) Weed allelopathy; its ecological impacts and future prospects. Journal of Crop Production 4(2): 43−119.

Rice EL. (1984) Allelopathy 2nd Edition. Academic Press, Sydney.

Seiter S. (2003) Managing Smooth Bedstraw in Forage Crops. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture University of New Hampshire, Cooperative Extension. Available at

http://extension.unh.edu/resources/files/Resource000032_Rep32.pdf (verified April 2010).

Wäckers FL. (2004) Assessing the suitability of flowering herbs as parasitoid food sources: flower attractiveness and nectar accessibility. 29 (3): 307−314 Available at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6WBP-49PYMBC1&_user=141304&_coverDate=03%2F31%2F2004&_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_acct=C000011678&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=141304&md5=dc7db1231fa45b9ba7ad2b8464b0e472 (verified April 2010).

Webb CJ, Sykes WR and Garnock-Jones PJ. (1988) Rubiaceae, Galium mollugo. Flora of New Zealand, Vol. IV, Naturalised Pteridophytes, Gymnosperms, Dicotyledons. Botany Division, DSIR, Christchurch, New Zealand. p. 1146.

Global present distribution data references

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) (2010) Global biodiversity information facility, Available at http://www.gbif.org/ (verified 16 March 2010).

Integrated Taxonomic Information System. (2010) Available at http://www.itis.gov/ (verified 16 Mar 2010).

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) (2010) w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, Available at http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html (verified 9 March 2010).

Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne. (2003) Census of Vascular Plants of Victoria. Available at http://www.rbg.vic.gov.au/research_and_conservation/plant_information/viclist (verified 16 March 2010).

United States Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Research Service, National Genetic Resources Program. Germplasm Resources Information Network - (GRIN) [Online Database]. Taxonomy Query. (2009) Available at http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/taxgenform.pl (verified 16 Mar 2010).

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.