Montpellier Cistus (Cistus monspeliensis)

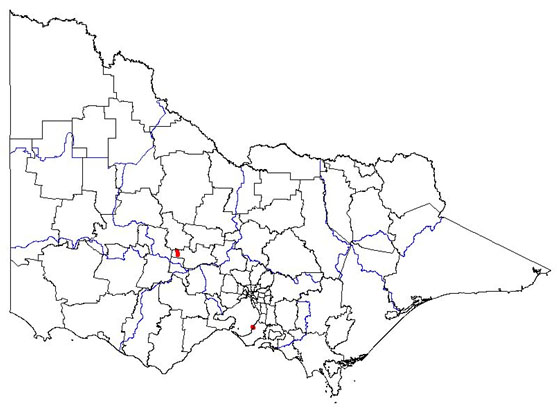

Present distribution

|  Map showing the present distribution of this weed. | ||||

| Habitat: Native to Southern Europe, Northern Africa and Western Asia. Reported invading pasture, and present in scrubland and pine plantations. | |||||

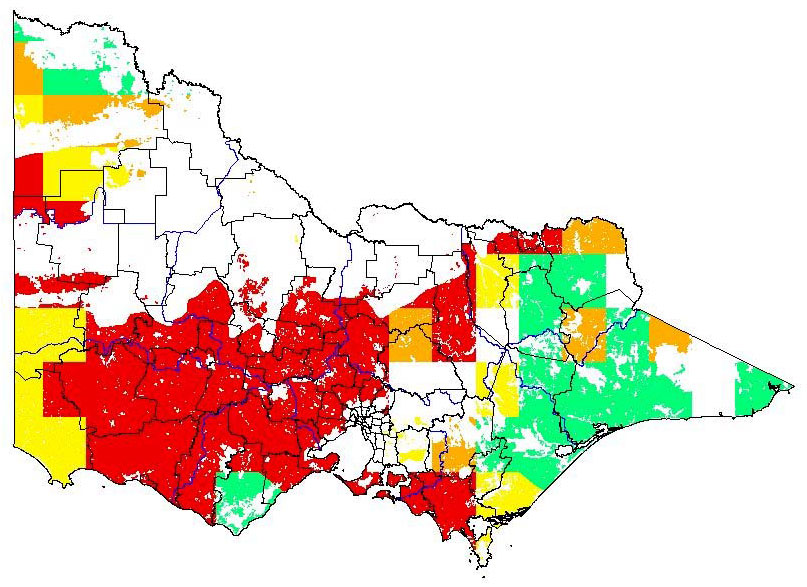

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Forest private plantation; forest public plantation; pasture dryland. Broad vegetation types Coastal scrubs and grassland; coastal grassy woodland; heathy woodland; lowland forest; heath; box ironbark forest; inland slopes and plains; sedge rich woodland; dry foothills forest; montane dry woodland; sub-alpine woodland; grassland; plains grassy woodland; valley grassy forest; herb-rich woodland; sub-alpine grassy woodland; montane grassy woodland; rainshadow woodland; mallee; mallee heath; boinka-raak; mallee woodland; wimmera / mallee woodland Colours indicate possibility of Cistus monspeliensis infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Can form dense stands, some nuisance factor (Pardini, Gispert & Dunko 2003). Other Cistus species have been linked to dermatitis and C. monspeliensis does have a complex chemical composition including extracts have been trailed for used against leukaemic cells (Oller-Lopez etal 2005). | ml | m |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | Planted as an ornamental | ml | m |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Other Cistus species have been linked to dermatitis and C. monspeliensis does have a complex chemical composition including extracts have been trailed for used against leukaemic cells (Oller-Lopez etal 2005). | l | m |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | No reports of structural damage however attempts of control have been taken at the clues cemetery, therefore must have some aesthetic issues (Clarke 2005). | ml | m |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Terrestrial species | l | m |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Terrestrial species | l | m |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | While stand present only low erosion levels have been reported however after a fire which the species needs for mass regeneration, large-scale erosion does occur (Pardini, Gispert & Dunko 2003 and Pardini, Gispert & Dunko 2004). | mh | mh |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | Competitive species direct replacement, if invades grasslands, biomass increase. Has also been linked to dieback in Pine trees biomass decrease (Pardini, Gispert & Dunko 2003 and Prota & Garau 1981). | mh | m |

| 9. Change fire regime? | As a species it requires a specific fire regime for regeneration, The moisture content of this plant has also been used as a model to predict the fire risk in Spain, therefore has a large influence on the fire regime (Castro, Tudela & Sebastia 2003). | mh | m |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC= Grassy Woodland (E); CMA= Corangamite; Bioreg= Warrnambool Plain; VH CLIMATE potential. Can become dominant leading to lower floral diversity especially in the herb layer. Major displacement of dominant sp. within a layer. | h | mh |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC= Shrubby Foothill Forest (D); CMA= Corangamite; Bioreg= Warrnambool Plain; VH CLIMATE potential. Can become dominant leading to lower floral diversity especially in the herb layer. Major displacement of dominant sp. within a layer. | h | mh |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC= Lowland Forest (LC); CMA= Corangamite; Bioreg= Victorian Volcanic Plain; VH CLIMATE potential. Can become dominant leading to lower floral diversity especially in the herb layer. Major displacement of dominant sp. within a layer. | h | mh |

| 11. Impact on structure? | Can invade and dominate shrub layer. Has been linked with degradation of soil, which can have flow through effects on all floral strata (Pardini, Gispert & Dunko 2003 and Pardini, Gispert & Dunko 2004). In addition to this It has been linked to dieback of pine species as have other species of this genus been reported to prevent the regeneration of other tree species (Prota & Garau 1981). | mh | mh |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | No specific data, however is a successful competitor. | mh | l |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | No specific data, however has been found to be poisonous to some species (Vincente Ruiz, San Andres Larrea & Capo Marti 1989). | mh | m |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | Can become dominant over other species, and if inedible due to toxic effects causes a net loss in food (Vincente Ruiz, San Andres Larrea & Capo Marti 1989). | ml | m |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | Visited by numerous insects (Clarke 2005). | mh | mh |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | Has been shown to be toxic to sheep and goats (Vincente Ruiz, San Andres Larrea & Capo Marti 1989). | ml | mh |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | Provides pollen and nectar for bees (Ortiz 1994). | ml | mh |

| 18. Provides harbour? | No specific reports of being more important than any other shrub species. | m | m |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | Can invade pasture, and has been found to be toxic therefore reducing fodder for stock (Pardini, Gispert & Dunko 2004 and Vincente Ruiz, San Andres Larrea & Capo Marti 1989). Also associated with dieback in Pinus radiata, (Forestry) (Prota & Garau 1981). | ml | mh |

| 20. Impact quality? | Toxic to sheep and goats, no specific fatalities reported, probably cause as least a loss of condition (Vincente Ruiz, San Andres Larrea & Capo Marti 1989). Also associated with dieback in Pinus radiata, (Forestry) (Prota & Garau 1981). | m | mh |

| 21. Affect land value? | No specific data, if recognised for causing stock poisoning, and not controlled would have a negative impact. | m | l |

| 22. Change land use? | If not controlled could have negative impacts on forestry (Prota & Garau 1981) and dryland pasture to rangeland grazing (Vincente Ruiz, San Andres Larrea & Capo Marti 1989), requiring control or a change in land use. | mh | m |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | Requires control for a harvest to be fulfilled (Prota & Garau 1981), also possible restriction of stock from infested areas at certain times of the year (Vincente Ruiz, San Andres Larrea & Capo Marti 1989). | mh | m |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Has been associated with dieback of Pinus radiata (Prota & Garau 1981). | mh | m |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | Like other cistus sp. mass germination occurs the winter following a fire, also a small proportion of the seed produced doesn't have dormancy imposed on them in the form of a hard seed coat, and can germinate seasonally (Quintana etal 2004 and Trabaud & Renard 1999). | mh | h |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | Light and litter cover have been found not toe effect germination, however as the species is reported only in dry scrub and open woodland there is an assumed establishment restraint (Clarke 2005 and Trabaud & Renard 1999). | mh | mh |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Requires fire for mass germination, can inhabit open woodland (Clarke 2005). | mh | mh |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Shrub | l | h |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | None described however, it does have a complex chemical composition and an impact of soil properties and biology has been reported in association with the species (Oller-Lopez etal 2005 and Pardini, Gispert & Dunko 2003). C. ladanifer has also had allelopathic properties described. | l | l |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Has been observed tolerating slashing at the Clunes cemetery (Clarke 2005). Has been found to cause poisoning in sheep and goats (Vincente Ruiz, San Andres Larrea & Capo Marti 1989), and high essential oil content may discourage other herbivory (Oller-Lopez etal 2005). | mh | mh |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Height and spread 1.25 x 1m Found to have competitive growth rate (Clemente, Rego & Correia 2005). | mh | m |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Fire kills mature plants but is a requirement for mass germination (Clemente, Rego & Correia 2005). Found to be more tolerant of saline levels than C.albidus under experimental condition (Sanchez-Blanco etal 2002). Frost can kill seedlings, however mature plants appear to be unaffected (Quintana etal 2004). Found to be more tolerant under water deficit conditions than C.albius (Sanchez-Blanco etal 2002). Only reported in dry habitats may have susceptibility to waterlogging. | mh | m |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | C. monspeliensis has been found to be highly self incompatible, requiring cross pollination for seed set (Bosch 1992). | l | h |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | Species of this genus are reputedly highly productive producing upwards of 200000 seeds in a season (Talavera, Gibbs & Herrera 1993). | h | m |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | There are two types of seed set those that can germinate within the next season and those with a dormancy imposed by a hard seed coat, which in most cases is split during the heat of a fire. These dormant seeds are believe to remain viable upwards of 10 years. | mh | m |

| 12. Reproductive period? | Stands of C. monspeliensis have been estimated to 15-years old, removing time taken to maturity gives 10+ years of reproductive potential (Pardini, Gispert & Dunko 2004). | h | mh |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | A shrub species, presumed like others of the genus, to take two years before flowing, and three years before any significant reproduction. | ml | m |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Sheep and ants have been reported as dispersal agents, however majority of dispersal believed to be through gravity (Clarke 2005, Ramos, Robles & Castro 2006 and Retana., Pico & Rodrigo 2004). | mh | mh |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | Gravity over time <500m (Clarke 2005) Ants <20m (Retana., Pico & Rodrigo 2004) Sheep with a digestion period of up to 96hrs, kilometres (Ramos, Robles & Castro 2006). | mh | m |

References

Bosch. J. (1992) Floral biology and pollinators of three co-occuring cistus species (Cistaceae). Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 109: 39-55.

Castro. F.X., Tudela. A. & Sebastia. M.T. (2003) Modeling moisture content in shrubs to predict fire risk in Catalonia (Spain). Agricultural and Forest Meteorology. 116: 49-59.

Clarke. E. (2005) ‘Wild’ Cistus L. (CISTACEAE) in Victoria- future problem weeds or benign escapees from cultivation? Muelleria. 21: 77-86.

Clemente. A.S., Rego. F.C. & Correia. O.A. (2005) Growth, water relations and photosynthesis of seedlings and resprouts after fire. Acta Oecologica. 27: 233-243.

Oller-Lopez. J.L., Rodriguez. R., Cuerva. J.M., Oltra. J.E., Bazdi. B. Dahdouh. A., Lamarti. A. & Mansour. A.I. (2005) Composition of the Essential Oils of Cistus ladaniferus and C. monspeliensis from Morrocco. Journal of Essential Oil Research. 17: 553-555

Ortiz. P.L. (1994) The Cistaceae as food resources for honey bees in SW Spain. Journal of Applied Research. 33: 136-144.

Pardini. G., Gispert. M. & Dunko. G., (2003) Runoff erosion and nutrient depletion in five Mediterranean soils of NE Spain under different land use. The Science of the Total Environment. 309: 213-224.

Pardini. G., Gispert. M. & Dunjo. G. (2004) Relative influence of wildfire on soil properties and erosion processes in different Mediterranean environments in NE Spain. Science of the Total Environment. 328: 237-246.

Prota. U. & Garau. R. (1981) Studies on pine dieback phenomena in Sardinia, with special reference to Pinus radiata D. Don. [Italian]. Studi Sassaresi, 27: 183-204.

Quintana. J.R., Cruz. A., Fernandez-Gonzalez. F., & Moreno. J.M. (2004) Time of germination and establishment success after fire of three obligate seeders in Mediterranean shrubland of central Spain. Journal of Biogeography. 31: 241-249.

Ramos. M.E., Robles. A.B. & Castro. J. (2006) Efficiency of endozoochorous seed dispersal in six dry-fruited species (Cistaceae): from seed ingestion to early seedling establishment. Plant Ecology. 185: 97-106.

Retana. J.F., Pico. X. & Rodrigo. A. (2004) Dual role of harvesting ants as seed predators and dispersers of a non-myrmechorous Mediterranean perennial herb. Oikos. 105: 377-385.

Sanchez-Blanco. M.J., Rodriguez. P., Morales. M.A., Ortuno. M.F. & Torrecillas. A. (2002) Comparative growth and water relations of Cistus albidus and Cistus monspeliensis plants during water deficit conditions and recovery. Plant Science. 162: 107-113.

Talavera. S., Gibbs. P.E. & Herrera. J. (1993) Reproductive biology of Cistus ladanifer (Cistaceae). Plant Systematics and Evolution. 186: 123-134.

Trabaud. L. & Renard. P. (1999) Do light and litter influence the recruitment of Cistus spp. stands? Israel Journal of Plant Sciences. 47: 1-9.

Torrecillas. A., Rodriguez. P. & Sanchez-Blanco. M.J. (2003) Comparison of growth, leaf water relations and gas exchange of Cistus albidus and C. monspeliensis plants irrigated with water of different NaCl salinity levels. Scientia Horticulturae. 97: 353-368.

Vincente Ruiz. M.L. de, San Andres Larrea. M.L. & Capo Marti. M.A., (1989) Toxicological study of ether extracts of Cistus monspeliensis in the mouse. [French] Revue de Medecine Veterinaire. 140: 207-211.

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) 2006, Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, viewed 28 Aug 2006,http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/

Calflora: Information on California plants for education, research and conservation. [web application]. 2006. Berkeley, California: The Calflora Database [a non-profit organization]. Available: http://www.calflora.org/ . (Accesses: 28 Aug 2006)

Clarke. E. (2005) ‘Wild’ Cistus L. (CISTACEAE) in Victoria- future problem weeds or benign escapees from cultivation? Muelleria. 21: 77-86.

Clemente. A.S., Rego. F.C. & Correia. O.A. (2005) Growth, water relations and photosynthesis of seedlings and resprouts after fire. Acta Oecologica. 27: 233-243.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2006, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed 28 Aug 2006, http://www.gbif.org/

Pardini. G., Gispert. M. & Dunko. G., (2003) Runoff erosion and nutrient depletion in five Mediterranean soils of NE Spain under different land use. The Science of the Total Environment. 309: 213-224.

Retana. J.F., Pico. X. & Rodrigo. A. (2004) Dual role of harvesting ants as seed predators and dispersers of a non-myrmechorous Mediterranean perennial herb. Oikos. 105: 377-385.

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.