Lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta)

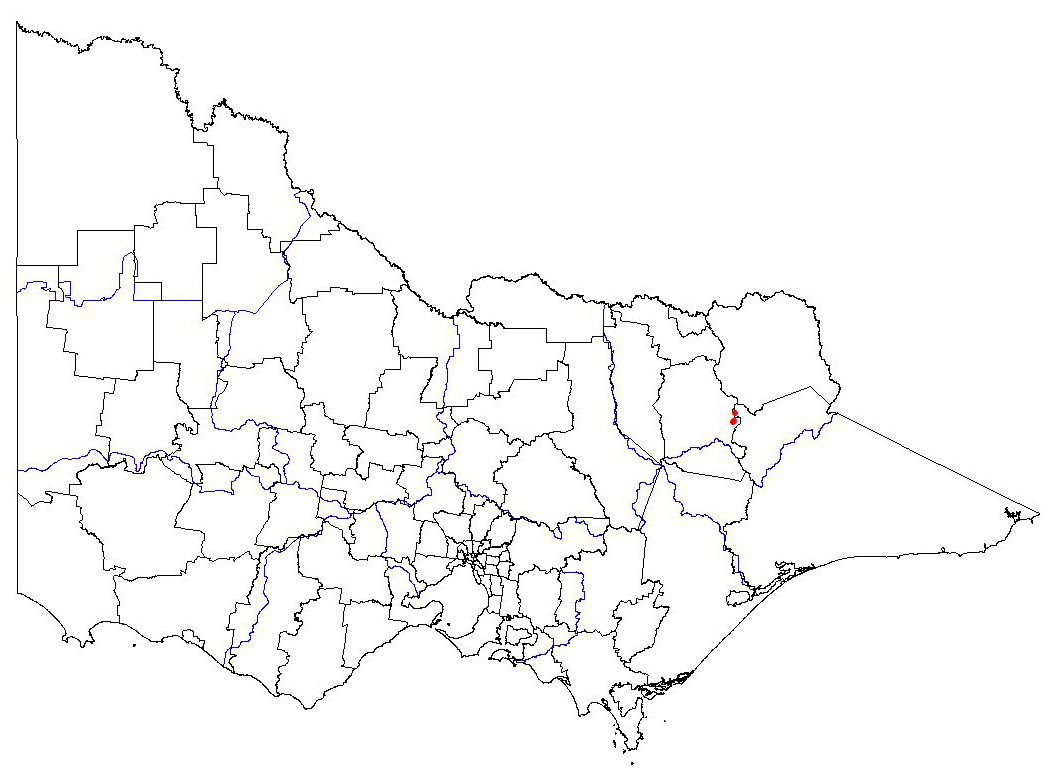

Present distribution

|  Map showing the present distribution of this weed. | ||||

| Habitat: Invades meadows, disturbed sites (Lotan & Perry 1983), tussock grassland, scrubland, open forests (Weber 2003). Grows in subalpine forest (Fall 1997) coastal mossy bogs, sand dunes, barrens, near shore in swampland, coastal ranges (Spencer 1995). Soils – infertile, widely varying characteristics, usually moist (Lotan & Perry 1983), decomposed granite (Vander Wall 2003). Tolerant to fire (Weber 2003), waterlogging (Coutts 1982), drought, frost (Lotan & Perry 1983). Intolerant to salinity (Hill 1999). | |||||

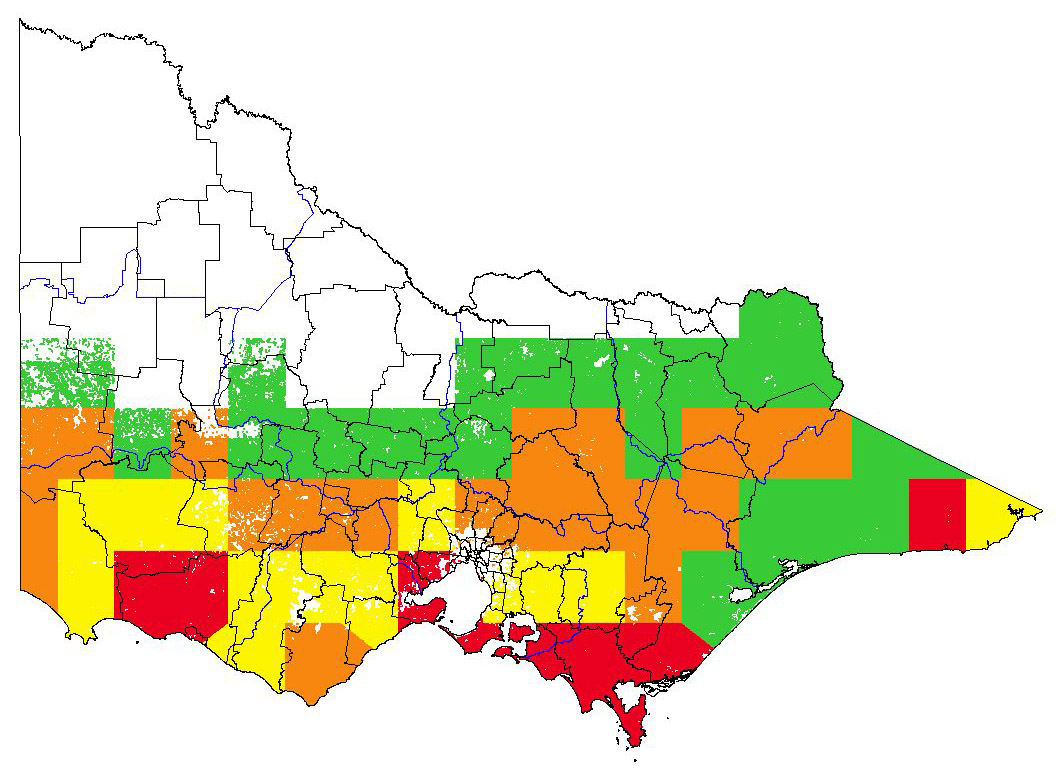

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Forestry; pasture dryland; pasture irrigation Ecological Vegetation Divisions Coastal; heathland; grassy/heathy dry forest; swampy scrub; freshwater wetland (permanent); treed swampy wetland; lowland forest; foothills forest; forby forest; damp forest; riparian; wet forest; high altitude shrubland/woodland; high altitude wetland; alpine treeless; granitic hillslopes; rocky outcrop shrubland; western plains woodland; basalt grassland; alluvial plains grassland; semiarid woodland; alluvial plains woodland; ironbark/box; riverine woodland/forest; freshwater wetland (ephemeral) Colours indicate possibility of Pinus contorta infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | 10-25 m tall (Spencer 1995) and “often exists in extensive, pure stands” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Major impediment to access waterways or machinery. Significant works required to provide reasonable access, tracks closed or impassable. | H | MH |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | “Invades and transforms native tussock grassland in New Zealand into species poor woodland and forest” (Weber 2003). Grows to 10-25 m tall (Spencer 1995) and “often exists in extensive, pure stands” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Major impact on recreation. Weeds obvious to most visitors, with visitor response complaints AND a major reduction in visitors. | H | MH |

| 3. Injurious to people? | No evidence to suggest injurious properties (Lotan & Perry 1983; Spencer 1995). No effect, no prickles, no injuries. | L | MH |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | “Invades and transforms native tussock grassland in New Zealand into species poor woodland and forest” (Weber 2003). Grows to 10-25 m tall (Spencer 1995) and “often exists in extensive, pure stands” (Lotan, & Perry 1983). Moderate visual effect. | ML | MH |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Terrestrial (Lotan & Perry 1983). Little or negligible affect on water flow. | L | MH |

| 6. Impact water quality? | “Lodgepole pine forests have a high value as watershed protectors... water quality from these stands is excellent. Most damage associated with logging is from road construction... shown to use about 50 percent more soil water during a summer than adjacent clearcuts” (Lotan & Perry 1983). No noticeable effect on dissolved oxygen OR light levels. | L | MH |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | “Invades and transforms native tussock grassland in New Zealand into species poor woodland and forest” (Weber 2003) and “has an amazing potential for invasion of meadows and disturbed sites” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Low probability of large scale soil movement; or decreases the probability of soil erosion. | L | MH |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | “Invades and transforms native tussock grassland in New Zealand into species poor woodland and forest” (Weber 2003). Biomass may increase. | L | MH |

| 9. Change fire regime? | “Invades and transforms native tussock grassland in New Zealand into species poor woodland and forest” (Weber 2003). Greatly changes the frequency and/or intensity of fire risk | H | MH |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC = Riparian Scrub (V); CMA = West Gippsland; Bioregion = Gippsland Plain; VH CLIMATE potential. Monoculture within a specific layer; displaces all species within a strata/layer. | H | H |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC = Sand Heathland (R); CMA = Port Phillip and Westernport; Bioregion = Gippsland Plain; VH CLIMATE potential. Monoculture within a specific layer; displaces all species within a strata/layer. | H | H |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC = Wet Heathland (LC); CMA = West Gippsland; Bioregion = Wilsons Promontory; VH CLIMATE potential. Monoculture within a specific layer; displaces all species within a strata/layer. | H | H |

| 11. Impact on structure? | “In some cases, lodgepole pines form what are apparently climax stands” (Lotan & Perry 1983). “Fires lead to a mass release of seeds, and the tree regenerates in extremely dense stands after fire, preventing the recruitment and growth of native plants” (Weber 2003). “In dense stands, virtually no understory vegetation grows” (Lotan & Perry 1983) and “in Sweden and other parts of northern Europe, there is concern that the widely planted North American conifer Pinus contorta (well known invader in several other parts of the world) will invade neighbouring landscapes dominated by native conifers” (Richardson & Rejmánek 2004), Invades “grass- and scrubland, open forests”…and “native tussock grassland in New Zealand [and transforms] into species poor woodland and forest” (Weber 2003). Major effects on all layers. Forms monoculture; no other strata/layers present. | H | H |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | “In dense stands, virtually no understory vegetation grows” and “as a result of fire, lodgepole pine often exists in extensive, pure stands with little or no seed source of associated species” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Likely to impact on threatened flora, however the effect on Bioregional Priority 1A and VROT species is as yet unknown. | MH | L |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | “In dense stands, virtually no understory vegetation grows” and “biotic diversity is generally low in dense, mature lodgepole pine stands.” Also “has an amazing potential for invasion of meadows and disturbed sites” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Likely to impact on threatened fauna, however the effect on Bioregional Priority and VROT species is as yet unknown. | MH | L |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | “In dense stands, virtually no understory vegetation grows” and “as a result of fire, lodgepole pine often exists in extensive, pure stands with little or no seed source of associated species.” Also “has an amazing potential for invasion of meadows and disturbed sites” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Habitat changed dramatically, leading to the possible extinction of non-threatened fauna. | H | MH |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | Although it is an “important food item for several species of small mammals and birds” such as squirrels, chipmunks, mice and voles, “biotic diversity is generally low in dense, mature lodgepole pine stands” (Lotan, Perry 1983). May provide some assistance in either food or shelter to desirable species. | MH | MH |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | No evidence to suggest injurious properties (Lotan, Perry 1983; Spencer 1995). No effect. | L | MH |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | “suffers attack from a variety of pest species, the three most important being the pine beauty moth, Panolis flammea, the European sawfly, Neoiprion sertifer and the larch bud moth, Zeiraphera diniana” in Britain (Trewhella et al. 2000). Supplies food for one or more minor pest spp | ML | H |

| 18. Provides harbor? | “In dense stands, virtually no understory vegetation grows” and “biotic diversity is generally low in dense, mature lodgepole pine stands” (Lotan & Perry 1983). No harbour for pest species. | MH | MH |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | Not listed as an agricultural weed (Randall 2007). However it “invades and transforms native tussock grassland in New Zealand into species poor woodland and forest” (Weber 2003) and “has an amazing potential for invasion of meadows and disturbed sites... In dense stands, virtually no understory vegetation grows... in general only a small proportion of the understory species in lodgepole pine stands are palatable” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Likely to invade pastures, however impact on the quantity or yield of produce is unknown. | M | L |

| 20. Impact quality? | Not listed as an agricultural weed (Randall 2007). However it “invades and transforms native tussock grassland in New Zealand into species poor woodland and forest” (Weber 2003) and “has an amazing potential for invasion of meadows and disturbed sites... In dense stands, virtually no understory vegetation grows... in general only a small proportion of the understory species in lodgepole pine stands are palatable” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Likely to invade pastures, however impact on the quality or yield is unknown. | M | L |

| 21. Affect land value? | Not listed as an agricultural weed (Randall 2007). However it “invades and transforms native tussock grassland in New Zealand into species poor woodland and forest” (Weber 2003) and “has an amazing potential for invasion of meadows and disturbed sites... In dense stands, virtually no understory vegetation grows... in general only a small proportion of the understory species in lodgepole pine stands are palatable” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Likely to invade pastures, however impact on land value is unknown. | M | L |

| 22. Change land use? | “Specific control methods for this species are not available... cutting trees may lead to seed release and requires follow-up programmes to treat seedlings” (Weber 2003). Therefore as “in dense stands, virtually no understory vegetation grows” (Lotan & Perry 1983). It may lead to downgrading of the priority land use, to one with less agricultural return. | MH | M |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | Not listed as an agricultural weed (Randall 2007). However it “invades and transforms native tussock grassland in New Zealand into species poor woodland and forest” (Weber 2003) and “has an amazing potential for invasion of meadows and disturbed sites... In dense stands, virtually no understory vegetation grows... in general only a small proportion of the understory species in lodgepole pine stands are palatable” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Likely to invade pastures, however impact on cost of harvesting is unknown. | M | L |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Mountain pine beetles, dwarf mistletoe (Lotan, Perry 1983). Lodgepole pine is a host species for sirex woodwasp (Sirex noctilio), which “has proven to be devastating to many commercial pine plantations, as well as natural forests, with mortality rates as high as 80%” (ISSG 2007), however this “is no longer regarded as a major threat to plantations due to improved stand management and biological controls” (van de Hoef 2003). Provides host to common pests, or diseases. | M | M |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | “Pinus contorta var. latifolia Engelm. do not open spontaneously after maturation. These serotinous cones remain closed until they are heated, usually by a forest fire” (Johnson & Gutsell 1993). However “for fresh seeds no cold stratification is necessary to induce germination” and “moisture and temperature are the two climatic factors most affecting seed germination” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Requires natural seasonal disturbances such as seasonal rainfall, spring/summer temperatures for germination. | MH | H |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | “establishment depends on disturbances, and seedlings are sensitive to shading and competition” (Weber 2003). Requires more specific requirements to establish. | ML | MH |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | “Invaded habitats: Grass- and scrubland, open forests... Invades and transforms native tussock grassland in New Zealand into species poor woodland and forest” (Weber 2003). “Has an amazing potential for invasion of meadows and disturbed sites” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Establishes in relatively intact OR only minor disturbed natural ecosystems. | MH | MH |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Evergreen tree (Weber 2003). Other. | L | MH |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | Leaf litter is listed as having a “moderate” allelopathic effect, “Pinus litter has an inhibiting effect on its own seed germination and seedling growth. Old growth pine stands slow in growth rates partially due to an auto-toxic effect” (Coder 1998). And in “dense stands, virtually no understory vegetation grows” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Allelopathic properties seriously affecting some plants. | MH | MH |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | “suffers attack from a variety of pest species, the three most important being the pine beauty moth, Panolis flammea, the European sawfly, Neoiprion sertifer and the larch bud moth, Zeiraphera diniana” in Britain (Trewhella et al. 2000). “Birds, voles and mice clip young germinants, but probably do not cause extensive losses” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Preferred food of herbivores (insects). Eliminated by moderate herbivory or reproduction entirely prevented. | L | MH |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | “Young, well-spaced lodgepole pine commonly outgrows its associates” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Rapid growth rate will exceed most other species of the same life form. | H | H |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | “Fires lead to a mass release of seeds, and the tree regenerates in extremely dense stands after fire, preventing the recruitment and growth of native plants” (Weber 2003). “The relative tolerance to waterlogging of the woody roots of lodgepole pine suggests that secondary growth might remain unhindered by localised waterlogging in the field” however some root dieback did occur” (Coutts 1982). Also “tolerant of high water tables or even flooding. At one site... trees that are flooded for a minimum of 47 days during the summer have larger diameters than adjacent unflooded trees, probably because of reduced competition on the flooded site.” Grows in areas where summer temperature may drop well below freezing and is “intermediate in its water needs” however it also “appears to compete well for water and occurs where other species may be excluded because of drought... On Zigzag soils in the Oregon Cascades, what are very droughty and infertile, lodgepole pine is the only tree species able to grow” (Lotan, Perry 1983). Listed as “absent from saline sites” (Hill 1999). Tolerant to fire, waterlogging, drought, frost. Intolerant to salinity. | H | MH |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | Sexual, both self and cross pollinated (Lotan & Perry 1983) | ML | MH |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | “Bear an abundance of serotinous cones containing viable seed. These unopened cones remain on the trees up to 40 years and may provide most of the seed for regenerating burned or logged areas... when the closed-cone habit prevails, the species has the ability to store seed from year to year, accumulating literally millions of seed per acre” (Lotan & Jensen 1970). Up to 9,000 cones have been counted on one tree (Lotan & Perry 1983). Above 2000 | H | MH |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | “Closed cones persist and accumulate on trees for decades” (Weber 2003). Few seeds still viable after 6 years (Lotan & Perry 1983). Greater than 25% of seeds can survive over 20 years. | H | MH |

| 12. Reproductive period? | “Pinus contorta can form stable communities for at least the length of one generation (approximately 100 years)” (Fall 1997). “Pure stands in and around Yellowstone National Park contains 300- and 400-year-old trees” (Lotan & Perry 1983). Mature plant produces viable propagules for 10 years or more, OR species forms a self-sustaining monoculture. | H | MH |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | “Short juvenile period (<10 year)” (Richardson, Rejmánek 2004). Greater than 5 years to reach sexual maturity. | L | H |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | “Produce winged seeds that are initially wind-dispersed but are gathered by rodents and cached in the soil” (Vander Wall 2003). Very light, wind dispersed seeds, OR has edible fruit that is readily eaten by highly mobile animals. | H | H |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | “Produce winged seeds that are initially wind-dispersed but are gathered by rodents and cached in the soil” (Vander Wall 2003) . Very likely that at least one propagule will disperse greater than one kilometre. | H | H |

References

Ashkannejhad S, Horton TR (2006) Ectomycorrhizal ecology under primary succession on coastal sand dunes: interactions involving Pinus contorta, suilloid fungi and deer. New Phytologist 169, 345-354.

Coder KD (1998) Potential allelopathy in different tree species. The University of Georgia Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources Extension. Available at http://warnell.forestry.uga.edu/service/library/for99-003/for99-003.pdf (verified 23 June 2009).

Coutts MP (1982) The tolerance of tree roots to waterlogging: V. growth of woody roots of sitka spruce and lodgepole pine in waterlogged soil. New Phytologist 90, 467-476.

Fall PL (1997) Fire history and composition of the subalpine forest of western Colorado during the Holocene. Journal of Biogeography 24, 309-325.

Hill MO, Mountford JO, Roy DB, Bunce RGH (1999) ECOFACT 2a technical annex – Ellenberg’s indicator values for British plants. NERC – Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, UK. Available at http://www.ceh.ac.uk/products/publications/documents/ECOFACT2a.pdf (verified 23 June 2009).

ISSG (2007) Global invasive species database. National Biological Information Infrastructure and IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group. Available at http://www.issg.org/database/species/ecology.asp?si=1211&fr=1&sts= (verified 23 June 2009).

Johnson EA, Gutsell SL (1993) Heat budget and fire behaviour associated with the opening of serotinous cones in two Pinus species. Journal of Vegetation Science 4, 745-750.

Lotan JE, Jensen CE (1970) Estimating seed stored in serotinous cones of lodgepole pine. Research Paper INT-83. United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Ogden, Utah. Research Paper INT-83.

Lotan JE, Perry DA (1983) Ecology and regeneration of lodgepole pine. Agricultural handbook No. 606. United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Washington, D.C.

Randall R (2007) Global compendium of weeds. Available at http://www.hear.org/gcw/species/pinus_contorta/ (verified 23 June 2009).

Richardson DM, Rejmánek M (2004) Conifers as invasive aliens: a global survey and predictive framework. Diversity and Distributions 10, 321-331.

Spencer D (2001) Conifers in the dry country. Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, Canberra. Available at https://rirdc.infoservices.com.au/items/01-146 (verified 10 June 2009).

Spencer R (Ed.) (1995) Horticultural Flora of South-Eastern Australia Volume 1. Ferns, Conifers and their Allies. UNSW Press.

Trewhella KE, Leather SR, Day KR (2000) Variation in the suitability of Pinus contorta (lodgepole pine) to feeding by three pine defoliators, Panolis flammea, Neodiprion sertifer and Zeiraphera diniana. Journal of Applied Entomology 124, 11-17.

Van de Hoef L (2003) Radiata pine for farm forestry. Department of Primary Industries, Victoria. Available at http://www.dpi.vic.gov.au/dpi/nreninf.nsf/childdocs/-1C62D26CD3AF6FE44A2568B300051289-0A38C6F4DA19A236CA256BC80005ACBD-5F35DFAFEA9EE75E4A256DEA00276C0FF64E4AF8E2F12AAECA256BCF000BBDE5?open (verified 23 June 2009).

Vander Wall SB (2003) Effects of seed size of wind-dispersed pine (Pinus) on secondary seed dispersal and the caching behaviour of rodents. Oikos 100, 25-34.

Weber E (2003) Invasive Plant Species of the World: A Reference Guide to Environmental Weeds. CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) (2009) Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, Available at http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/ (verified 22 June 2009).

Australian Plant Name Index (APNI) http://www.cpbr.gov.au/cgi-bin/apni (verified 16 June 2009).

Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) (2006) Flora information system [CD-ROM], Biodiversity and Natural Resources Section, Viridans Pty Ltd, Bentleigh.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) (2009) Global biodiversity information facility, Available at http://www.gbif.org/ (verified 22 June 2009).

Integrated Taxonomic Information System. (2009) Available at http://www.itis.gov/ (verified 16 June 2009).

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) (2009) w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, Available at http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html (verified 16 June 2009).

United States Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Research Service, National Genetic Resources Program. Germplasm Resources Information Network - (GRIN) [Online Database]. Taxonomy Query. (2009) Available at http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/taxgenform.pl (verified 16 June 2009).

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.