Leymus (Leymus arenarius)

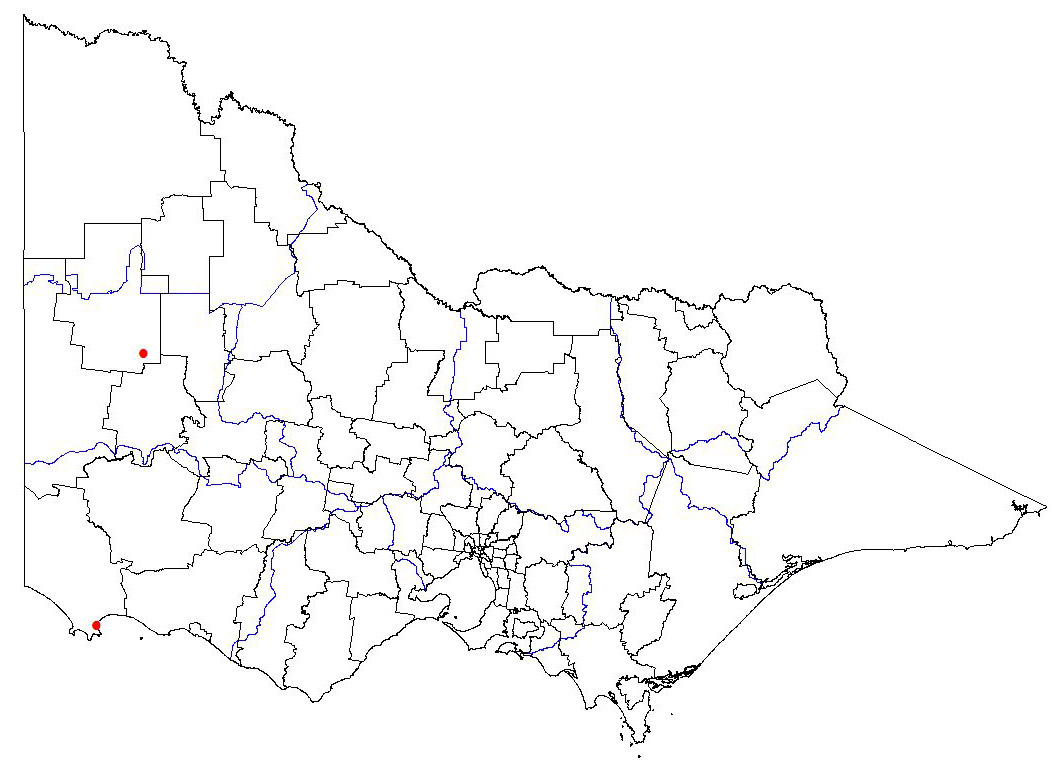

Present distribution

|  Map showing the present distribution of this weed. | ||||

| Habitat: “Leymus arenarius is primarily a coastal species” (Greipsson and Davy 1996b). “Leymus have scarcely been utilised, especially from the species in the present study, L. arenarius (L.) Hochst. and L. mollis (Trin.) Pilger. As they are native plants of the circumpolar regions, they possess some valuable characteristics such as tolerance to low temperature, freezing and ice encasement, in addition to tolerance to salinity, alkalinity and drought” (Anamthawat-Jonsson et al. 1997). “The micro environment on gravely roadsides close to the black pavement provides suitable conditions for germination of L. arenarius similar to those found in the beach sand” (Greipsson et al. 1997). Lymegrass, on the other hand, is highly adapted to marginal habitats such as eroded, low fertility, saline and alkaline soils” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). “In Finland, L. arenarius is found on the sea-shore as well as on inland sands along lakes and rivers” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). | |||||

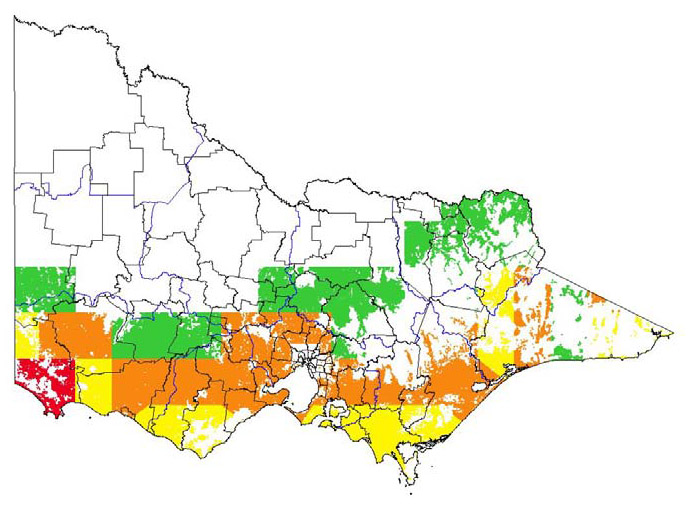

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Broadacre cropping; horticulture seasonal; pasture dryland; pasture irrigation; water Ecological Vegetation Divisions Coastal; freshwater wetland (permanent); foothills forest; high altitude wetland; saline wetland Colours indicate possibility of Leymus arenarius infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | “Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is a perennial with long rhizomes, thick culms 0.5-2m tall, spikes 12-35cm long with 12-30 nodes, spikelets usually two per node, seeds numerous” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). Elymus arenarius (syn. of Leymus arenarius) is “a robust bluish-grey perennial, forming large tufts or masses… Spreading by its extensively creeping rhizomes and by seeds, sometimes dominating large areas of dunes” (Hubbard 1968). “Densely tufted” (Brickell 1996). “In Finland, L. arenarius is found on the sea-shore as well as on inland sands along lakes and rivers” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Major impediment to access waterways or machinery. Significant works required to provide reasonable access, tracks closed or impassable. | H | M |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | “Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is a perennial with long rhizomes, thick culms 0.5-2 m tall, spikes 12-35 cm long with 12-30 nodes, spikelets usually two per node, seeds numerous” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). Elymus arenarius (syn. of Leymus arenarius) is “a robust bluish-grey perennial, forming large tufts or masses… Spreading by its extensively creeping rhizomes and by seeds, sometimes dominating large areas of dunes” (Hubbard 1968). “Densely tufted” (Brickell 1996). “In Finland, L. arenarius is found on the sea-shore as well as on inland sands along lakes and rivers” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Some recreational uses affected. | MH | M |

| 3. Injurious to people? | “L. arenarius in particular, has an accent history of human consumption for bread making, probably due to large seed size and availability of extensive natural stands” (Anamthawat-Jonsson et al. 1997). Also not described as injurious in Greipsson and Davy 1994a, 1995, 1996a, 1996b; Greipsson et al. 1997; Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995. No effect, no prickles, no injuries. | L | M |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | “Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is a perennial with long rhizomes, thick culms 0.5-2 m tall, spikes 12-35 cm long with 12-30 nodes, spikelets usually two per node, seeds numerous” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). Elymus arenarius (syn. of Leymus arenarius) is “a robust bluish-grey perennial, forming large tufts or masses… Spreading by its extensively creeping rhizomes and by seeds, sometimes dominating large areas of dunes” (Hubbard 1968). “Densely tufted” (Brickell 1996). Moderate visual effect. | ML | M |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | “Seeds of Leymus arenarius were collected from 34 locations in Finland…those temporarily reached by seawater are referred to as “littoral” (Greipsson et al. 1997). “In Finland, L. arenarius is found on the sea-shore as well as on inland sands along lakes and rivers” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Little or negligible effect on water flow. | L | M |

| 6. Impact water quality? | “Seeds of Leymus arenarius were collected from 34 locations in Finland…those temporarily reached by seawater are referred to as “littoral” (Greipsson et al. 1997). “In Finland, L. arenarius is found on the sea-shore as well as on inland sands along lakes and rivers” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). No noticeable effect on dissolved O2 or light levels. | L | M |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | “Natural stands of Leymus arenarius are harvested on a large scale in Iceland for sowing in reclamation programmes to combat unstable and eroding sands. The harvest period is short and susceptible to autumn gales and grazing…It has been used to stabilise drifting sands” (Greipsson and Davy 1995). “On the south coast of Iceland, sand stabilisation has saved several successful fishing villages from being abandoned” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Low probability of large scale soil erosion or decreases the probability of soil erosion. | L | MH |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | “The absence of safe-sites for germination could also be a reason for the decline of L. arenarius after the invasion of other species…Plants add litter and dampen temperature oscillations, and uniform temperature inhibits germination of L. arenarius…Competition with other dune-building grasses such as Ammophila arenaria and Elymus farctus may restrict its distribution in certain areas in England” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). “Seed harvested from wild populations of Leymus arenarius is sown extensively in Iceland to stabilise sandy barrens” (Greipsson and Davy 1996b). Although continuous exposure of seeds to seawater inhibits germination, sea-dispersed seeds or L. arenarius were found to colonise rapidly the newly created volcanic island Surtsey” (Greipsson et al. 1997). Biomass may increase. | L | M |

| 9. Change fire regime? | “Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is a perennial with long rhizomes, thick culms 0.5-2 m tall, spikes 12-35 cm long with 12-30 nodes, spikelets usually two per node, seeds numerous” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). Elymus arenarius (syn. of Leymus arenarius) is “a robust bluish-grey perennial, forming large tufts or masses” (Hubbard 1968). “Densely tufted” (Brickell 1996). Greatly changes the frequency and intensity of fire risk. | H | M |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC = Coastal Dune Scrub (V); CMA = Glenelg Hopkins; Bioregion = Warnambool Plain; VH CLIMATE potential. “Competition with other dune-building grasses such as Ammophila arenaria and Elymus farctus may restrict its distribution in certain areas in England…When sand deposition cease, other grass species, such as Festuca ruba, Festuca ovina and Poa spp., invade the dunes and eventually replace L. arenarius…The absence of safe-sites for germination could also be a reason for the decline of L. arenarius after the invasion of other species…Plants add litter and dampen temperature oscillations, and uniform temperature inhibits germination of L. arenarius” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). “Such a gap/depth-sensing mechanism might contribute to the observed decrease of L. arenarius in the vegetational cover in late successional stage of Icelandic sand dunes, when other species have increased their cover (Greipsson and Davy 1994a). Minor displacement of some dominant or indicator spp. within any one strata/layer (eg. ground cover, forbs, shrubs & trees). | ML | M |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC = Damp Heathland (D); CMA = Glenelg Hopkins; Bioregion = Glenelg Plain; H CLIMATE potential. “Competition with other dune-building grasses such as Ammophila arenaria and Elymus farctus may restrict its distribution in certain areas in England…When sand deposition cease, other grass species, such as Festuca ruba, Festuca ovina and Poa spp., invade the dunes and eventually replace L. arenarius…The absence of safe-sites for germination could also be a reason for the decline of L. arenarius after the invasion of other species…Plants add litter and dampen temperature oscillations, and uniform temperature inhibits germination of L. arenarius” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). “Such a gap/depth-sensing mechanism might contribute to the observed decrease of L. arenarius in the vegetational cover in late successional stage of Icelandic sand dunes, when other species have increased their cover (Greipsson and Davy 1994a). Minor displacement of some dominant or indicator spp. within any one strata/layer (eg. ground cover, forbs, shrubs & trees). | ML | M |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC = Coastal Saltmarsh (LC); CMA = West Gippsland; Bioregion = Gippsland Plain; VH CLIMATE potential. “Competition with other dune-building grasses such as Ammophila arenaria and Elymus farctus may restrict its distribution in certain areas in England…When sand deposition cease, other grass species, such as Festuca ruba, Festuca ovina and Poa spp., invade the dunes and eventually replace L. arenarius…The absence of safe-sites for germination could also be a reason for the decline of L. arenarius after the invasion of other species…Plants add litter and dampen temperature oscillations, and uniform temperature inhibits germination of L. arenarius” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). “Such a gap/depth-sensing mechanism might contribute to the observed decrease of L. arenarius in the vegetational cover in late successional stage of Icelandic sand dunes, when other species have increased their cover (Greipsson and Davy 1994a). Minor displacement of some dominant or indicator spp. within any one strata/layer (eg. ground cover, forbs, shrubs & trees). | ML | M |

| 11. Impact on structure? | “Competition with other dune-building grasses such as Ammophila arenaria and Elymus farctus may restrict its distribution in certain areas in England…When sand deposition cease, other grass species, such as Festuca ruba, Festuca ovina and Poa spp., invade the dunes and eventually replace L. arenarius…The absence of safe-sites for germination could also be a reason for the decline of L. arenarius after the invasion of other species…Plants add litter and dampen temperature oscillations, and uniform temperature inhibits germination of L. arenarius” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). “Such a gap/depth-sensing mechanism might contribute to the observed decrease of L. arenarius in the vegetational cover in late successional stage of Icelandic sand dunes, when other species have increased their cover (Greipsson and Davy 1994a). Minor or negligible effect on <20% of the floral strata/layers present; usually only affecting on of the strata. | L | M |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | No information found. | MH | L |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | No information found. | MH | L |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | No information found. | M | L |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | “Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is a perennial with long rhizomes, thick culms 0.5-2 m tall” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). Elymus arenarius (syn. of Leymus arenarius) is a grass “forming large tufts or masses… spreading by its extensively creeping rhizomes” (Hubbard 1968). “Competition with other dune-building grasses such as Ammophila arenaria and Elymus farctus may restrict its distribution in certain areas in England and rabbit grazing may be a factor affecting its abundance and distribution… Wild stands of L. arenarius are valuable for grazing for sheep... It is however, very vulnerable to grazing” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). “Lymegrass has a long history of food and non-food uses, i.e. as grains for baking and hay for animal feed” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). “Frequent strong gales disperse the seed, or it is grazed by flocks of grey lag geese” (Greipsson and Davy 1995). May provide some assistance in either food or shelter to desirable species. | MH | M |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | “Rabbit grazing may be a factor affecting its abundance and distribution… Wild stands of L. arenarius are valuable for grazing for sheep...It is however, very vulnerable to grazing” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). “Lymegrass has a long history of food and non-food uses, i.e. as grains for baking and hay for animal feed” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). Also not described as injurious to fauna in Greipsson and Davy 1994a, 1995, 1996a, 1996b; Greipsson et al. 1997; or Anamthawat-Jonsson et al. 1997. No effect. | L | M |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | “Rabbit grazing may be a factor affecting its abundance and distribution… Wild stands of L. arenarius are valuable for grazing for sheep, especially in the spring. It is however, very vulnerable to grazing” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). “Lymegrass has a long history of food and non-food uses, i.e. as grains for baking and hay for animal feed” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). Supplies food for serious pest (e.g. rabbits and foxes), but at low levels (e.g. foliage). | MH | MH |

| 18. Provides harbour? | “Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is a perennial with long rhizomes, thick culms 0.5-2 m tall” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). Elymus arenarius (syn. of Leymus arenarius) is a grass “forming large tufts or masses… Spreading by its extensively creeping rhizomes” (Hubbard 1968). “Rabbit grazing may be a factor affecting its abundance and distribution” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). May have capacity to provide harbour and permanent warrens for foxes and rabbits throughout the year. | H | M |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | “Due to this potential agricultural value, we have initiated research and breeding effort to improve lymegrass as a perennial grain crop” (Anamthawat-Jonsson et al. 1997). “Although lymegrass has a long history of food and non-food uses, i.e. as grains for baking and hay for animal feed…Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is suitable for cultivation in the northern latitudes where climatic conditions do not allow conventional cereal crops…Lymegrass, on the other hand, is highly adapted to marginal habitats such as eroded, low fertility, saline and alkaline soils” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). “The quality of flour made from seeds of L. arenarius is considered to be high… It is however, very vulnerable to grazing… Breeding between Leymus species and wheat (Triticum aestivum) has resulted in hybrids that are more resistant to viral infection” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Little or negligible affect on quantity of yield. | L | MH |

| 20. Impact quality? | “Due to this potential agricultural value, we have initiated research and breeding effort to improve lymegrass as a perennial grain crop” (Anamthawat-Jonsson et al. 1997). “Although lymegrass has a long history of food and non-food uses, i.e. as grains for baking and hay for animal feed…Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is suitable for cultivation in the northern latitudes where climatic conditions do not allow conventional cereal crops…Lymegrass, on the other hand, is highly adapted to marginal habitats such as eroded, low fertility, saline and alkaline soils” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). “The quality of flour made from seeds of L. arenarius is considered to be high… It is however, very vulnerable to grazing… Breeding between Leymus species and wheat (Triticum aestivum) has resulted in hybrids that are more resistant to viral infection” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Little or negligible affect on quality of yield. | L | MH |

| 21. Affect land value? | “Due to this potential agricultural value, we have initiated research and breeding effort to improve lymegrass as a perennial grain crop” (Anamthawat-Jonsson et al. 1997). “Although lymegrass has a long history of food and non-food uses, i.e. as grains for baking and hay for animal feed…Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is suitable for cultivation in the northern latitudes where climatic conditions do not allow conventional cereal crops…Lymegrass, on the other hand, is highly adapted to marginal habitats such as eroded, low fertility, saline and alkaline soils” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). “The quality of flour made from seeds of L. arenarius is considered to be high… It is however, very vulnerable to grazing… Breeding between Leymus species and wheat (Triticum aestivum) has resulted in hybrids that are more resistant to viral infection” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Little or none. | L | MH |

| 22. Change land use? | “Due to this potential agricultural value, we have initiated research and breeding effort to improve lymegrass as a perennial grain crop” (Anamthawat-Jonsson et al. 1997). “Although lymegrass has a long history of food and non-food uses, i.e. as grains for baking and hay for animal feed…Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is suitable for cultivation in the northern latitudes where climatic conditions do not allow conventional cereal crops…Lymegrass, on the other hand, is highly adapted to marginal habitats such as eroded, low fertility, saline and alkaline soils” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). “The quality of flour made from seeds of L. arenarius is considered to be high… It is however, very vulnerable to grazing… Breeding between Leymus species and wheat (Triticum aestivum) has resulted in hybrids that are more resistant to viral infection” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Little or no change. | L | MH |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | “Due to this potential agricultural value, we have initiated research and breeding effort to improve lymegrass as a perennial grain crop” (Anamthawat-Jonsson et al. 1997). “Although lymegrass has a long history of food and non-food uses, i.e. as grains for baking and hay for animal feed…Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is suitable for cultivation in the northern latitudes where climatic conditions do not allow conventional cereal crops…Lymegrass, on the other hand, is highly adapted to marginal habitats such as eroded, low fertility, saline and alkaline soils” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). “The quality of flour made from seeds of L. arenarius is considered to be high… It is however, very vulnerable to grazing… Breeding between Leymus species and wheat (Triticum aestivum) has resulted in hybrids that are more resistant to viral infection” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Little or none. | L | MH |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | “Ergot (Claviceps purpurea) is found on the spikes of L. arenarius especially during summers with much rainfall. Although ergotted heads are poisonous when consumed, they do have pharmaceutical uses. It is possible that fields of L. arenarius could be infected with the ergot and subsequently harvested. Ergot is used to make the drugs ergotamine, ergobasine and lysergic acid derivatives” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). “Leymus have scarcely been utilised, especially from the species in the present study, L. arenarius (L.) Hochst. and L. mollis (Trin.) Pilger. As they are native plants of the circumpolar regions, they possess some valuable characteristics such as…resistance to fungal diseases such as leaf rust and mildew” Anamthawat-Jonsson et al. 1997). Host to major and severe disease or pest of important agricultural produce. | H | MH |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | “The micro environment on gravely roadsides close to the black pavement provides suitable conditions for germination of L. arenarius similar to those found in the beach sand where high fluctuations of temperature are important for germination of seed buried at a shallow depth. (Greipsson et al. 1997). Plants add litter and dampen temperature oscillations, and uniform temperature inhibits germination of L. arenarius” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). The ‘safe site’ for germination should therefore be deep enough in sand to avoid light but sufficiently shallow to sense temperature fluctuation, where moisture conditions would probably be better than on the surface” (Greipsson and Davy 1994a). “Stratification for 14 days at 15°C was a prerequisite for nearly complete germination but stratification did not affect the initial rate of germination…Imbibition of a certain amount of water is a prerequisite for germination” (Greipsson and Davy 1996a). Requires natural seasonal disturbances such as seasonal rainfall, spring/summer temperatures for germination. | MH | H |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | The ‘safe site’ for germination should therefore be deep enough in sand to avoid light but sufficiently shallow to sense temperature fluctuation, where moisture conditions would probably be better than on the surface” (Greipsson and Davy 1994a). “Plants add litter and dampen temperature oscillations, and uniform temperature inhibits germination of L. arenarius” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Forty percent “of seedlings emerged when germinating seeds were buried with 15 cm of sand, whereas none emerged from burial under 20 cm of sand” (Greipsson and Davy 1996b). Requires more specific requirements to establish (e.g. open space or bare ground with access to light and direct rainfall). Requires more specific requirements to establish (eg. open space or bare ground with access to light and direct rainfall). | ML | MH |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | “In Finland, L. arenarius is found on the sea-shore as well as on inland sands along lakes and rivers” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Establishes in relatively intact or only minor disturbed natural ecosystems (eg. wetlands, riparian, riverine, grasslands, open woodlands) | MH | MH |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | “Leymus arenarius (L.)…is a perennial, rhizomatous dune-building grass” (Greipsson and Davy 1995). Grass. | MH | MH |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | “The absence of safe-sites for germination could also be a reason for the decline of L. arenarius after the invasion of other species…Plants add litter and dampen temperature oscillations, and uniform temperature inhibits germination of L. arenarius” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Also not described as allelopatic in Greipsson and Davy 1994a, 1995, 1996a, 1996b; Greipsson et al. 1997; Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995; or Anamthawat-Jonsson et al. 1997. None. | L | L |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | “Rabbit grazing may be a factor affecting its abundance and distribution…Best results [for establishment on reclamation sites] are obtained if plants are fertilised and protected from livestock grazing for several years… Wild stands of L. arenarius are valuable for grazing for sheep, especially in the spring. It is however, very vulnerable to grazing” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). “Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is a perennial with long rhizomes…[and] seeds numerous” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). Consumed and recovers slowly. Reproduction strongly inhibited by herbivory but still capable of vegetative propagule production (by rhizomes or tubers); weed may still persist. | ML | MH |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | No information found. | M | L |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | As they are native plants of the circumpolar regions, they possess some valuable characteristics such as tolerance to low temperature, freezing and ice encasement, in addition to tolerance to salinity, alkalinity and drought” (Anamthawat-Jonsson et al. 1997). Those temporarily reached by seawater are referred to as “littoral” (Greipsson et al. 1997). Lymegrass, on the other hand, is highly adapted to marginal habitats such as eroded, low fertility, saline and alkaline soils” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). These traits could increase the use of cereals if incorporated into hybrids, especially in cold temperate areas or where soils are affected by high salinity” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Highly resistant to frost and waterlogging, highly tolerant to salinity and drought. Unknown to fire. Highly resistant to at least two of drought, frost, fire, waterlogging, and salinity not susceptible to more than one (cannot by drought or waterlogging). | H | MH |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | “Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is a perennial with long rhizomes…[and] seeds numerous” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). “Seed dispersal along roadsides is aided by mowers and traffic” (Greipsson et al. 1997). Both vegetative and sexual reproduction (vegetative may be via cultivation, but not propagation). | H | MH |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | “Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is a perennial with long rhizomes, thick culms 0.5-2 m tall, spikes 12-35 cm long with 12-30 nodes, spikelets usually two per node, seeds numerous” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). Large numbers (200-300) of seeds per spike and cold tolerance are found in L. arenarius” (Greipsson and Davy 1994b). Elymus arenarius (syn. of Leymus arenarius) is “a robust bluish-grey perennial, forming large tufts or masses” (Hubbard 1968). “Densely tufted” (Brickell 1996). May produce four or more flowering stems as it is a tufted grass; 300 seeds/spike x 4 spikes=1,200. Plus rhizomes. 1000-2000 propagules. | MH | M |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | “The inhibition of germination by salinity was an osmotically enforced dormancy effect rather than a lethal, toxic one…Clarke (1964) found that pre-soaking caryopses (with and without glumes) in water increased eventual germination and suggested that water-soluble inhibitors may be involved in seed dormancy; Harris (1982) obtained similar results” (Greipsson and Davy 1994a). “Seed buried (presumably by sand accretion) at such a depth may therefore remain dormant and contribute to the seed bank” (Greipsson and Davy 1994a). “Seeds of L. arenarius have been reported to exhibit a strong dormancy…Light has previously been found to affect seed germination adversely; geminating seeds have poor prospects for surviving the harsh micro climate on the surface of sands and therefore light inhibition can prevent untimely germination” (Greipsson and Davy 1996a). “Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is a perennial with long rhizomes…[and] seeds numerous” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). This species is known to exhibit dormancy but it is unknown how long it can remain in the seed bank. Greater than 25% of seeds survive 5 years, or vegetatively reproduces. | L | M |

| 12. Reproductive period? | “Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is a perennial” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). Mature plant may produce viable propagules for 3-10 years. | MH | ML |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | “Leymus arenarius (L.)…is a perennial, rhizomatous dune-building grass” (Greipsson and Davy 1995). “Lymegrass (L. arenarius; L. mollis) is a perennial with long rhizomes, thick culms 0.5-2 m tall, spikes 12-35 cm long with 12-30 nodes, spikelets usually two per node, seeds numerous” (Anamthawat-Jonsson 1995). May produce propagules between 1-2 years after germination, or vegetative propagules become separate individuals between 1-2 years. | MH | M |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | “Frequent strong gales disperse the seed, or it is grazed by flocks of grey lag geese” (Greipsson and Davy 1995). Very light, wind dispersed seeds, or bird dispersed seeds, or has edible fruit that is readily eaten by highly mobile animals. | H | MH |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | “Although continuous exposure of seeds to seawater inhibits germination, sea-dispersed seeds or L. arenarius were found to colonise rapidly the newly created volcanic island Surtsey” (Greipsson et al. 1997). “Frequent strong gales disperse the seed, or it is grazed by flocks of grey lag geese” (Greipsson and Davy 1995). Very likely that at least one propagule will disperse greater than one kilometre. | H | H |

References

Anamthawat-Jonsson K. (1995) Wide-hybrids between wheat and lymegrass: breeding and agricultural potential. Icel. Agr. Sci. 9:101-113. Available at:

http://www.landbunadur.is/landbunadur/wgsamvef.nsf/8bbba2777ac88c4000256a89000a2ddb/13305063e376dedf00256b0400402078/$FILE/gr-bu10-kaj.PDF (verified

26/05/2010).

Anamthawat-Jonsson K, Bodvarsdottir S.K, Bragason B.T,Gudmundsson J, Martin P.K, and Koebner R.M.D. (1997) Wide hybridization between wheat (Triticum L.) and lymegrass (Leymus Hochst.) Euphytica. 93: 293-300. Available at: http://www.springerlink.com/content/x5173730228n0762/fulltext.pdf (verified 17/05/2010).

Brickell C. (Ed.) (1996) A-Z Encyclopedia of Garden Plants. The Royal Horticultural Society. Covent Garden Books, London.

Greipsson S, Ahokas H, and Vahamiko S. (1997) A rapid adaptation to low salinity of inland-colonizing populations of the littoral grass Leymus arenarius. Int. J. Platn Sci. 158(1): 73-78. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/pss/2475131 (verified 17/05/2010).

Greipsson S. and Davy A.J. (1994a) Germination of Leymus arenarius and its significance for land reclamation in Iceland. Annals of Botany. 73, 393-401. Available at:

http://aob.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/73/4/393 (verified 26/05/2010).

Greipsson S. and Davy A.J. (1994b) Leymus arenarius. Characteristics and uses of a dune-building grass. Ice. Agr. Sci. 8: 41-50. Available at:

http://www.landbunadur.is/landbunadur/wgsamvef.nsf/8bbba2777ac88c4000256a89000a2ddb/939d8549cf43014200256dfe00495414/$FILE/gr-bu8-sg.PDF (verified

17/05/2010).

Greipsson S. and Davy A.J. (1995) Seed mass and germination behaviours in populations of the dune-building grass Leymus arenarius. Annals of Botany. 76: 493-501. Available at: http://aob.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/76/5/493 (verified 17/05/2010).

Greipsson S. and Davy A.J. (1996a) Aspects of seed germination in the dune-building grass Leymus arenarius. Icel. Agr. Sci. 10:209-217. Available at:

http://www.landbunadur.is/landbunadur/wgsamvef.nsf/0/1d601ad17ec03bfc00256dea003dc9da/$FILE/gr-bu10-sg.PDF (verified 26/05/2010).

Greipsson S. and Davy A.J. (1996b) Sand accretion and salinity as constraints on the establishment of Leymus arenarius for land reclamation in Iceland. Annals of Botany. 78:611- 618. Available at: http://aob.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/78/5/611 (verified 17/05/2010).

Hubbard C.E. (1968) Grasses: A guide to their structure, identification, uses and distribution in the British Isles. Revised edn. Penguin Books; Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England.

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) (2010) Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, Available at

http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/ (verified 01/06/2010).

Department of the Environment and Heritage (Commonwealth of Australia). (1993 – On-going) Australian Plant Name Index (APNI) http://www.cpbr.gov.au/apni/index.html

(verified 11/05/2010).

Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) (2006) Flora information system [CD-ROM], Biodiversity and Natural Resources Section, Viridans Pty Ltd, Bentleigh.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) (2008) Global biodiversity information facility, Available at http://www.gbif.org/ (verified 05/05/2010).

Integrated Taxonomic Information System. (2009) Available at http://www.itis.gov/ (verified 11/05/2010).

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) (2010) w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, Available at http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html (verified 05/05/2010).

United States Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Research Service, National Genetic Resources Program. Germplasm Resources Information Network - (GRIN) [Online

Database]. Taxonomy Query. (2007) Available at http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/taxgenform.pl (verified 11/05/2010).

Walsh N and Stajsic V. (2007) A Census of the Vascular Plants of Victoria. 8th Edn. Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne.

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.