Kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobata)

Present distribution

|  This weed is not known to be naturalised in Victoria | ||||

| Habitat: Native to China, Kudzu is a climber reported in scrub, forest especially on margins and in gaps, woodland, riparian vegetation, timber plantations, pasture, roadsides, disturbed and waste places (Forseth & Innis 2004; Miller & Edwards 1983; Mitich 2000; Van Der Maesen 1985; Weber 2003). It has been reported to grow at altitudes of 2000m however it is more frequent at lower elevations (Van Der Maesen 1985) | |||||

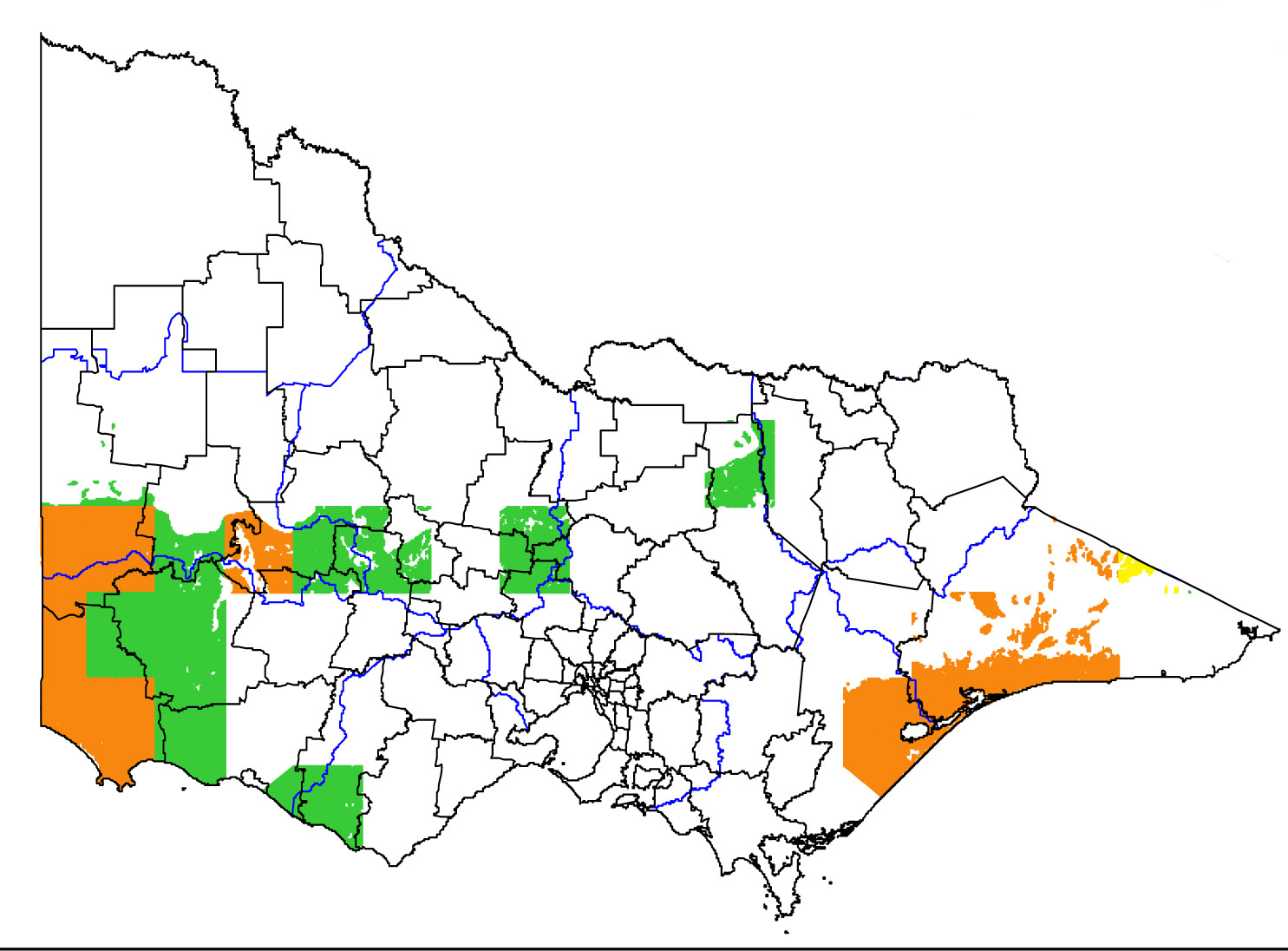

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Forest private plantation; forest public plantation; horticulture; pasture dryland; pasture irrigation Broad vegetation types Coastal scrubs and grassland; coastal grassy woodland; heathy woodland; lowland forest; inland slopes woodland; sedge rich woodland; grassland; plains grassy woodland; valley grassy forest; herb-rich woodland; montane grassy woodland; riverine grassy woodland; riparian forest Colours indicate possibility of Pueraria montana var. lobata infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | If it doesn’t have anything to grow over it is restricted to the ground, however its ability to cover trees to abandoned cars and other obstacles would result in any actions to create access through to be taken cautiously (Mitich 2000). In addition to this its need for total eradication to maintain any sense of control would make this plant a major impediment (Forseth & Innis 2004). | h | mh |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | In the US invasion by Kudzu in Chickamaugam Chattanooga and Vicksburg National Military Park has altered the landscape decreasing the historic value of the park (Forseth & Innis 2004). | mh | mh |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Kudzu is used in Chinese medicine and is being investigated for beneficial properties (Keung & Vallee 1998; Miller & Edwards 1983). Reported to have barbed hairs which can cause irritation (PFAF 2007). Little else is reported about this irriation therefore to be only a mild irritant. | ml | ml |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | Kudzu has been reported to periodically interrupt power supplies as it can topple powerlines, short-out powerlines and damage equipment (Forseth & Innis 2004; Mitich 2000). When it grows over railway lines it can potentially causing slippages and derailments (Forseth & Innis 2004). Kudzu has also been reported to grow over and cover barns, abandoned cars and houses (Mitich 2000). | h | h |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Doesn’t do well in waterlogged soils (Mitich 2000). Therefore there is a low potential for the species impeding water flow. | l | m |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Doesn’t do well in waterlogged soils (Mitich 2000). Therefore there is a low potential for the species impeding water flow. | l | m |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | Has a well developed root system and has been used historically for erosion control (Forseth & Innis 2004). Kudzu does however die back in winter (Mitich 2000). This could leave the soil surface exposed to erosion, however this is not viewed as large scale erosion, and the root system of kudzu would therefore prevent large scale erosion. | l | mh |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | The growth of Kudzu would cause a net increase in biomass, however its ability to smother shrubs and trees, until under the weight of the kudzu they fall would result in an overall decrease in biomass (Forseth & Innis 2004). | h | mh |

| 9. Change fire regime? | As Kudzu dies back in winter, in the US it is said to increase the fire hazard for timber plantations during winter, it is also said to provide a fire ladder increasing the chances of a crown fire (Forseth & Innis 2004; Harrington, Rader-Dixon & Taylor 2003). This coupled with the alterations in biomass could result in a moderate change in both fire intensity and timing, however there isn’t any data on this species in Australian vegetation. | mh | mh |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC= Plains Grassy Woodland (E); CMA= East Gippsland; Bioreg= Gippsland Plain; M CLIMATE potential. Kudzu is smother other species including trees and form monocultures, the only species reported to be able to co-exist with kudzu are spring ephemeral understorey species, which can store up reserves before being shaded out by the kudzu in spring (Forseth & Innis 2004). Even with a medium CLIMATE match it is still believed that kudzu will be capable of forming a monoculture as it has done in areas of New York which is in the northern extreme of the species range in the US (Frankel 1989). | h | h |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC= Riparian Shrubland (R); CMA= East Gippsland; Bioreg= East Gippsland Lowlands; M CLIMATE potential. Kudzu is smother other species including trees and form monocultures, the only species reported to be able to co-exist with kudzu are spring ephemeral understorey species, which can store up reserves before being shaded out by the kudzu in spring (Forseth & Innis 2004). Even with a medium CLIMATE match it is still believed that kudzu will be capable of forming a monoculture as it has done in areas of New York which is in the northern extreme of the species range in the US (Frankel 1989). | h | h |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC= Heathy Woodland (LC); CMA= East Gippsland; Bioreg= Gippsland Plain; M CLIMATE potential. Kudzu is smother other species including trees and form monocultures, the only species reported to be able to co-exist with kudzu are spring ephemeral understorey species, which can store up reserves before being shaded out by the kudzu in spring (Forseth & Innis 2004). Even with a medium CLIMATE match it is still believed that kudzu will be capable of forming a monoculture as it has done in areas of New York which is in the northern extreme of the species range in the US (Frankel 1989). | h | h |

| 11. Impact on structure? | Kudzu is smother other species including trees and form monocultures, the only species reported to be able to co-exist with kudzu are spring ephemeral understorey species, which can store up reserves before being shaded out by the kudzu in spring (Forseth & Innis 2004). Even with a medium to low CLIMATE match it is still believed that kudzu will be capable of forming a monoculture as it has done in areas of New York which is in the northern extreme of the species range in the US (Frankel 1989). If it doesn’t form a complete monoculture it is believed it will have a major effect on all layers. | h | mh |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | Invasion by Kudzu has been identified as a threatening process to Trillium reliquum and endangered plant species in the US (Heckel 2004). While it has not been identified as a threat to any Australian species its nature of smothering all before it would have a significant impact threatened species. | mh | mh |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | No specific information, however sever alteration of the habitat and biodiversity of the flora is likely to have some impact upon any threatened fauna (Forseth & Innis 2004). | mh | l |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | There is no data on the species impact on fauna species. Kudzu may have significant changes however to habitat structure and floral diversity which would impact upon food supply could have a significant impact on fauna (Forseth & Innis 2004). | h | m |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | The leaves are edible and the flowers may be visited by a suite of species (Hipps 1994). It is not known to what extent any Australian species will use this plant. | m | l |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | No evidence of this. | m | l |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | Reported to be eaten by deer and rabbits (Hipps 1994). It is not known however to what extent rabbits utilise the species. | mh | m |

| 18. Provides harbor? | Tangled mess can cover abandoned cars and buildings (Mitich 2000). Therefore there is a high potential for kudzu to provide shelter in some form to any species. | h | m |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | Comparable in nutritive value with crop species such as alfalfa and has been used a s a fodder source in the past, however as it has it produces lower yields and is difficult to harvest it’s use in this fashion has been phased out (Hipps 1994). In the US losses in forestry productivity have been estimated to as much as $500,000,000 per year (Forseth & Innis 2004). When invading pasture, it would produce lower yields but could still be managed, where as in forestry production the plants ability to smother and kill trees has been found to have significant impact on yield. | H | H |

| 20. Impact quality? | Found not to effect milk or meat (Corley, Woldeghebriel & Murphy 1997). It is unknown if competition with kudzu effects the quality of the timber which is available to be harvested. | m | l |

| 21. Affect land value? | No specific data, however its impact on the US timber industry may indicate potential future impacts. | m | l |

| 22. Change land use? | Invasion by this species does have a significant impact upon forestry operations (Forseth & Innis 2004). It is unknown to what extent this species would have on the type of land used taking place on invaded land. | m | l |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | One of the reasons it was abandoned as a fodder crop in the US is that the vines interfered with the harvesting equipment (Miller & Edwards 1983). As it has the potential to increase the risk of fire during winter in forestry situations extra labour would be expected to be needed to mitigate this (Harrington, Rader-Dixon & Taylor 2003) . | m | m |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Can be effected by Halo blight (Pseudomonas syringae pathovar phaseolicola) a fungus which can effect beans (Hipps 1994). | m | h |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | Seeds have been found to germinate under a broad range of temperature, pH, osmotic stress and depth in soil conditions representative of conditions found in North Carolina between spring and autumn, however without scarification between 7 and 17% of seeds germinated where as with scarification up to 100% germination was observed (Susko, Mueller & Spears 1999; Susko, Mueller & Spears 2001). Therefore there is a seasonal component to germination and while the majority of seeds need an additional event such as fire, some are capable of germination under seasonal conditions. | m | mh |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | There is somewhat conflicting data on the shade tolerance of this species, Tsugawa, Tange & Mizuta (1985) found that seedlings would grow under 83% shade, however the development of the root system was found to be effected. Where as Carter & Teramura (1988) found the species poorly adapted as an understorey species and only one planted individual survived four months once being planted out under canopy. These two observations show that while the species is capable of growing under shade, the growth is hampered in such a way that establishment is unlikely as with a compromised root system the plant may not have stored sufficient reserves to over-winter. Generally the consensus of this species is that it grows in forest margins or in gaps (Burrows 1989; Cronk & Fuller 1995; Henderson 1995; Tsugawa et al 1992; Weber 2003). | ml | mh |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Reported to invade open woodland, pasture and riparian habitats (Burrows 1989; Miller & Edwards 1983; Mitich 2000; Weber 2003). | mh | h |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Leguminous vine (Susko, Mueller & Spears 2001). | mh | h |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | The leaves of this species have been found to contain substances that suppress the germination and reduce the growth rate of lettuce, it is unknown however to what extent these substances have on plants under field conditions (Kato-Noguchi 2003). | m | h |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Has been historically used as a fodder crop and continual over grazing for a two year period has been found to potentially eliminate the species, however under natural levels of herbivory from deer or rabbits etc it is able to grow faster than its eaten (Hipps 1994). | mh | h |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Seedlings compete poorly in comparison with other aggressive weeds, however once established vines can grow between 10-30m per season and up to 30cm a day and are able to smother 35 metre tall trees (Mitich 2000). | mh | h |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Has a well developed root system which makes it drought tolerant and able to be used as an emergency fodder source (Miller & Edwards 1983). Tolerant of heavy metals (Brown, Brown & Allen 2001). Young stems are sensitive to frost and in temperate climates, frosts cause established plants to die back in autumn however they are able to then regrow from the root system in spring (Mitich 2000). Fire can kill young plants, however well established plants will regrow from the roots and fire can also encourage germination (Hipps 1994). Reported to grow poorly in waterlogged soil (Mitich 2000). Unknown tolerance of salinity. | mh | mh |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | Able to reproduce sexually and vegetatively, flowers however are only produced on vertically growing vines exposed to direct sunlight (Forseth & Innis 2004; Mitich 2000). | h | h |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | Vegetatively the species can produce a new plant at each node, nodes are reported to occur at approximate intervals of 30cm and vines have been reported growing 10-30m in a season, with each plant producing multiple vines, therefore vegetative reproduction could account for more than 50 new plants per season (Hipps 1994; Mitich 2000). The species capacity for sexual reproduction is not specifically known. In the US seed production is said to be infrequent and often not viable, this has not however been quatitified (Susko, Mueller & Spears 1999; Mitich 2000). Has been reported to flower in Australia unknown fruiting capacity (Van Der Maesen 1985). Flowers and fruits are produced only on vertically growing vines exposed to direct sunlight (Mitich 2000). | m | l |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | Unknown; it is however a legume species with a dormancy inducing seed coat and therefore probable for the seeds to remain viable for a number of years (Forseth & Innis 2004). | m | l |

| 12. Reproductive period? | Grows over existing vegetation forming a monoculture (Forseth & Innis 2004). | h | h |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | New crowns can vegetatively spread within there first year and rooted nodes can become separate within the first year of rooting as the above ground biomass dies back over winter (Mitich 2000; Tsugawa, Hori & Sasek 1995). It is not known when the plant can start flowering. | h | h |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Seeds are reported to be dispersed by birds and mammals (Weber 2003). Specific species are not mentioned however. | h | mh |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | Specific dispersal distances are not reported, Hipps (1994) states that the seeds are not easily spread by birds and other animals. | m | l |

References

Brown P.A., Brown J.M. & Allen S.J., 2001, The application of kudzu as a medium for the absorption of heavy metals from dilute aqueous waste streams. Bioresource Technology. 78: 195-201.

Burrows J.E., 1989, Kudzu vine – a new plant invader of South Africa. Veld & Flora. 75: 116-117.

Carter G.A. & Teramura A.H., 1988, Vine photosynthesis and relationships to climbing mechanics in a forest understorey. American Journal of Botany. 75: 1011-1018.

Corley .R.N., Woldeghebriel A. & Murphy M.R., 1997, Evaluation of the nutritive value of kudzu (Pueraria lobata) as a feed for ruminants. Animal Feed Science

Technology. 68: 183-188.

Cronk Q.C.B. & Fuller J.L., 1995, Plant Invaders. The threat to natural ecosystems. Chapman & Hall. London. 1995.

Forseth I.N. & Innis A.F., 2004, Kudzu (Pueraria montana): History, Physiology, and Ecology combine to make a major ecosystem threat. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 23: 401-413.

Harrington T.B., Rader-Dixon L.T. & Taylor J.W., 2003, Kudzu (Pueraria montana) community response to herbicides, burning, and high-density loblolly pine. Weed Science. 51: 965-974.

Heckel C.D., 2004, Impacts of exotic invasive vines on the ecology and reproduction of the endangered Trillium reliquum. Masters Thesis. Georgia Southern University.

Henderson L., 1995, Plant Invaders of Southern Africa: Plant Protection Research Institute Handbook No 5. Agricultural Research Council.

Hipps C.B., 1994, Kudzu. Horticulture. 72: 36-39.

Kato-Noguchi H., 2003, Allelopathic substances in Pueraria thunbergiana. Phytochemistry. 63: 577-580.

Keung W.M. & Vallee B.L., 1998, Kudzu root: An Ancient Chinese source of modern antidipsotropic agents. Phytochemistry. 47: 499-506.

Miller J.H. & Edwards B., 1983, Kudzu: Where did it come from? And how can we stop it? Southern Journal of Applied Forestry. 7: 165-169.

Mitich L.W., 2000, Intriguing world of weeds. Kudzu [Pueraria lobata (Willd.) Ohwi]. Weed Technology. 14: 231-235.

PFAF: Plants for a Future. Edible, medicinal and useful plants for a healthier world. viewed 29 Mar 2007, http://pfaf.org/

Susko D.J., Mueller J.P. & Spears J.F., 1999, Influence of environmental factors on germination and emergence of Pueraria lobata. Weed Science. 47: 585-588.

Susko D.J., Mueller J.P. & Spears J.F., 2001, An evaluation of methods for breaking seed dormancy in Kudzu (Pueraria lobata). Canadian Journal of Botany. 79: 197- 203.

Tsugawa H., Hori Y. & Sasek T.W., 1995, Spatial distribution of parent stumps and rooted nodes just after the first overwintering of Kudzu (Pueraria lobata Ohwi) stands differing in spacing. Science reports of faculty of agriculture, Kobe University. 21: 121-124.

Tsugawa H., Shimizu T., Sasek T.W. & Nishikawa K., 1992, The climbing strategy of Kudzu-vine (Pueraria lobata Ohwi) I. Comparisons of branching behaviour, and dry matter and leaf area production between staked and non-staked Kudzu plants. Science reports of faculty of agriculture, Kobe University. 20: 1-6.

Tsugawa H., Tange M. & Mizuta Y., 1985, Influence of shade treatment on leaf and branch emergence, and dry matter production of Kudzu vine seedlings (Pueraria lobata Ohwi). Science reports of faculty of agriculture, Kobe University. 16: 359-367.

Van Der Maesen L.J.G., 1985, Revision of the genus Pueraria DC. With some notes on Teyleria Backer. Agricultural University Wageningen.

Weber E. 2003, Invasive plant species of the world: a reference guide to environmental weeds, CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) 2007, Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, viewed 15 Feb 2007, http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2007, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed 1 Mar 2007, http://www.gbif.org/

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) 2007, w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, viewed 23 Feb 2007, http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.