Esperato grass (Achnatherum tenacissima)

Present distribution

|  This weed is not known to be naturalised in Victoria | ||||

| Habitat: Native to semi-arid areas in southwestern Europe, north Africa and western Asia. Found in alpha steppes and grasslands where it can tolerate light shade (Haase et al 1995). | |||||

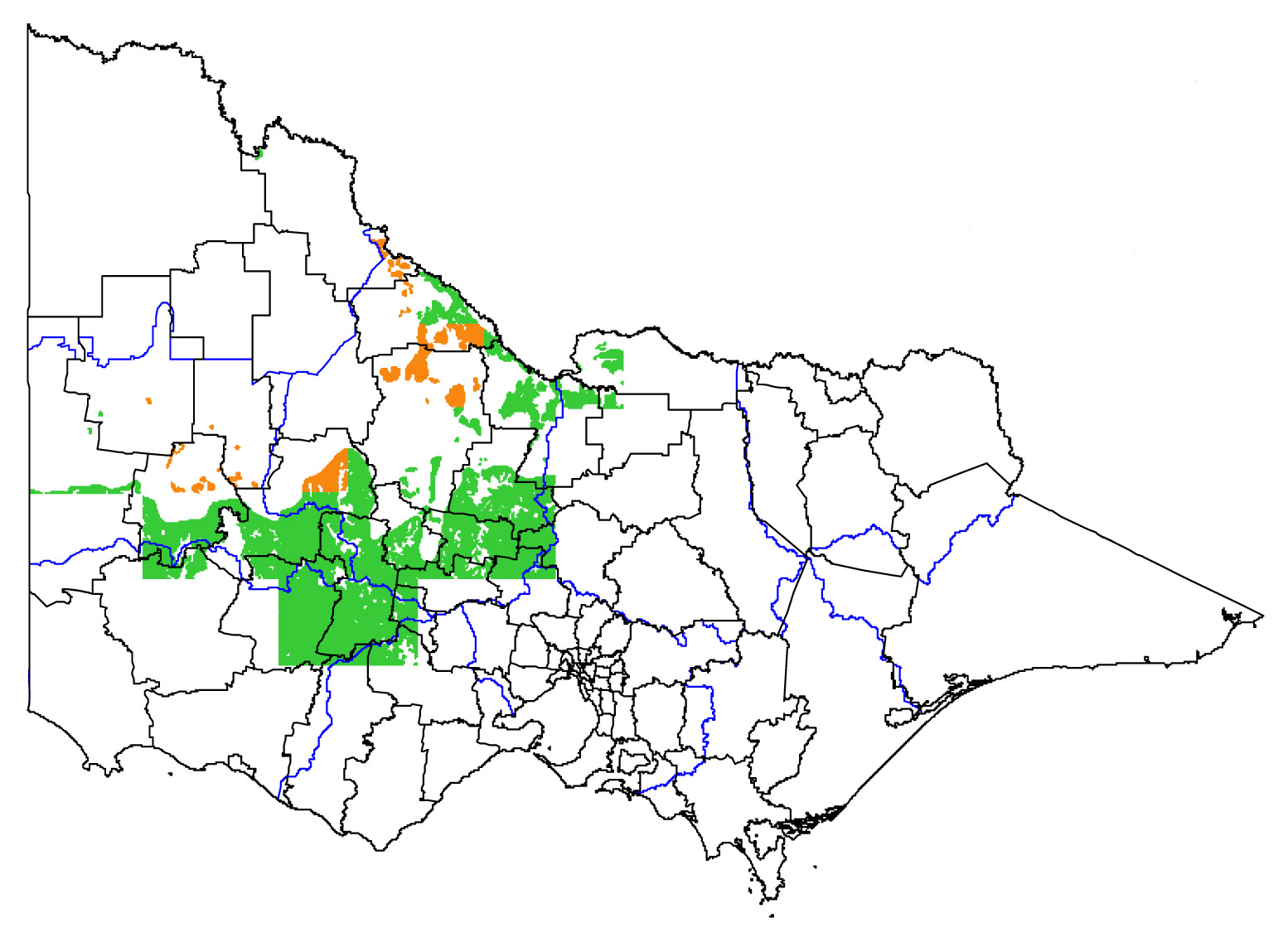

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Pasture dryland; pasture irrigated Broad vegetation types Coastal scrubs and grassland; coastal grassy woodland; montane dry woodland; grassland; plains grassy woodland; montane grassy woodland. Colours indicate possibility of Achnatherum tenacissima infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Perennial tussock grass growing to 1m (Haase et al 1995). Grows in grasslands. Minimum or negligible impact on human access. | L | H |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | Weed not documented to impact upon tourism. | L | MH |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Esparto fibres are widely used in Mediterranean countries for rope, mat and basket manufacture. In these instances ‘esparto fibres have been described as a cause of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in stucco makers’ .. ‘the dust derived from esparto fibres can induce occupational asthma in an exposed subject’ (Baz et al 1999). However, in its natural environment, weed not known to affect people. | L | MH |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | Weed not documented to impact upon cultural sites. | L | MH |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Terrestrial species (Haase et al 1995). | L | H |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Terrestrial species (Haase et al 1995). | L | H |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | Experiments carried out showed that where A. tenacissima is growing, surface runoff and erosion is negligible but quite high in the bare areas surrounding the tussock (Cerda 1997). Often used in the ‘protection against soil erosion’ (Gasque & Garcia-Fayos 2003). Low probability of large scale soil movement. | L | H |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | Aerial biomass increases with altitude with dense formations above 1100m (Lloveras et al 2006). Grows in grasslands and bare areas. Biomass may increase. | L | H |

| 9. Change fire regime? | Perennial tussock grass growing to 1m (Haase et al 1995). Grows in grasslands so may contribute to a minor change in the frequency and / or intensity of fire. | ML | H |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC=Plains grassland (BCS =E) CMA=Corangamite; Bioreg=Victorian volcanic plain; CLIMATE potential=L. At 900m occurs in scattered populations but above 1100m populations become dense formations (Lloveras et al 2006). May lead to a minor displacement of some dominant species within the lower strata. | ||

| (b) medium value EVC | This weed is unlikely to occur in medium value EVCs in Victoria. | ||

| (c) low value EVC | This weed is unlikely to occur in medium value EVCs in Victoria. | L | MH |

| 11. Impact on structure? | At 900m occurs in scattered populations but above 1100m populations become dense formations (Lloveras et al 2006). In Spain it was found that cover is high on moderate slopes and that the cover of other typical Mediterranean species was negatively correlated (Alados et al 2006). At times, the plant may have a major effect on the lower strata. | MH | H |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | This species is not documented as posing an additional risk to threatened flora. | MH | L |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | This species is not documented as posing an additional risk to threatened fauna. | MH | L |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | Not documented as having an effect on non-threatened fauna species. | L | MH |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | Weed not known to provide benefits or facilitate the establishment of indigenous fauna. | H | MH |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | Not documented as being injurious to fauna. | L | MH |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | Not documented as a food source to pests. | L | MH |

| 18. Provides harbour? | Not documented as providing harbour to pest species. | L | MH |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | Not a weed of agriculture (Holm et al 1979). | L | MH |

| 20. Impact quality? | Not a weed of cropping. | L | MH |

| 21. Affect land value? | Weed not known to affect value of land. | L | MH |

| 22. Change land use? | Weed not known to cause a change in priority of land use. | L | MH |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | Not a weed of cropping. | L | MH |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Weed not a known host or vector for disease of agriculture. | L | MH |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | ‘The germination season in natural populations occurs from autumn to early spring, always depending on the amount of precipitation’ (Gasque & Garcia-Fayos 2003). Requires natural seasonal conditions for germination. | MH | H |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | In Spain has been found amongst smaller shrubs (Alados et al 2005). Can be grown in a lightly shaded position (PFAF 2004). Can establish under a moderate canopy. | MH | H |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | In Spain it dominates wide areas of semi-arid areas. Found in alpha steppes and grassland (Pugnaire & Haase 1996). Establishes in relatively intact ecosystems. | MH | H |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Perennial tussock grass (Haase et al 1995). Life form – grass | MH | H |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | None described. | L | MH |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Overgrazing contributes to reducing A. tenacissima (Lloveras et al 2006). Also worth noting that post-dispersal predation by granivorous ants may significantly limit recruitment of A> tenacissima (Haase et al 1995). Reproduction strongly inhibited by herbivory but still capable of vegetative production. | ML | H |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Has opportunistic growth compared to Lygeum spartum, another tussock grass (Pugnaire & Haase 1996). Moderately rapid growth. | MH | H |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Can cope with drought and erratic rainfall (Pugnaire & Haase 1996). Three years after fire, the high degree of cover of A. tenacissima was similar to that of unburned areas (Martinez-Sanchez et al 1997). Not frost tender and can tolerate temperatures down to between -5 and -10C. Can tolerate strong winds but not maritime exposure (PFAF 2004). Highly resistant to drought and fire. Tolerant of frost. Maybe susceptible to waterlogging and salinity. | MH | H |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | In Spain a study showed ‘high allocation to sexual reproduction, although S. tenacissima is a clonal plant which normally reproduces vegetatively by tillering’ (Haase et al 1995). Both vegetative and sexual reproduction. | H | H |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | ‘Exceptionally heavy flowering and fruiting was observed in the semi-arid perennial tussock grass Stipa tenacissima L.’ Plant can have up to 167 spikes per tussock with an average of 234 flowers per spike of which 87.5% may produce fruits Haase et al 1995). Plant may produce greater than 2000 propagules per flowering event. | H | H |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | Can maintain germinability for two or three years however ‘germination percentage decreased substantially and significantly from 50% to less than 15% after 28 months’ (Gasque & Garcia-Fayos 2003). Seeds survive less than 5 years. | L | H |

| 12. Reproductive period? | Perennial grass (Haase et al 1995). Would produce viable propagules for greater than 2 years but insufficient information to determine whether it would produce viable propagules for greater than 10 years or form self-sustaining dense monocultures. | MH | H |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | Insufficient information to determine time to reach reproductive maturity. | M | L |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | ‘Most seeds fall within 1 - 3 m of the parent plants .. The sharp callus and stiff bristles are probably also a means for occasional long distance dispersal by animals’. Also eaten by birds. (Haase et al 1995). Mainly spread by gravity but can also be spread by attaching to humans or animals. | ML | H |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | ‘Most seeds fall within 1 - 3 m of the parent plants’ (Haase et al 1995). Very unlikely to disperse more than 200m and most will be less than 20m. | L | H |

References

Alados, C.L., Gotor, P., Ballester, P., Navas, D., Escos, J.M., Navarro, T. & Cabezudo, B. 2005, ‘Association between competition and facilitation processes and vegetation spatial patterns in alpha steppes’ Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, vol. 87, pp. 103-113.

Baz, G., Hinojosa, M., Quirce, S. & Cuveas, M. 1999, ‘Occupational asthma caused by esparto grass (Stipa tenacissima) fibers’, Allergy, vol. 54, p86.

Cerda, A. 1997, ‘The effect of patchy distribution of Stipa tenacissima L. on runoff and erosion’, Journal of Arid Environments, vol. 36, no.1, pp. 37-51.

Clayton, W.D., Harman, K.T. & Williamson, H. (2002 onwards). World grass species: descriptions, identification, and information, viewed 11 Sep 2006,

http://www.kew.org/data/grasses–db.html

Gasque, M. & Garcia-Fayos, P. 2003, ‘Seed dormancy and longevity in Stipa tenacissima L. (Poaceae)’, Plant Ecology, vol. 168, pp. 279-290.

Haase, P., Pugnaire, I. & Incoll, L.D. 1995, ‘Seed production and dispersal in the semi-arid tussock grass Stipa tenacissima L. during masting’, Journal of Arid Environments, vol. 31, pp. 55-65.

Holm, L., Pancho, J.V., Herberger, J.P. & Plucknett, D.L. 1979, A geographical atlas of world weeds, John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Lloveras, J., Gonzalez-Rodriguez, A., Vazquez-Yanez, O., Pineiro, J., Santamaria, O., Olea, L. & Poblaciones, M.J. ‘Aerial biomass assessment of Stipa tenacissima in forest ecosystems’, Sociedad Espanola para el Estudio de los Pastos, pp. 601-603, CAB Abstracts.

Martinez-Sanchez, J.J., Herranz, J.M., Guerra, J. & Trabaud, L. 1997, ‘Influence of fire on plant regeneration in a Stipa tenacissima L. community in the Sierra Larga mountain range’, Israel Journal of Plant Sciences, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 309-316, CAB Abstracts.

Plants for a Future (PFAF) 2004, Stipa tenacissima, Plants for a future database, viewed 11 Sep 2006, http://www.ibiblio.org/pfaf/D_search.html

Pugnaire, F.I. & Haase, P. 1996, ‘Comparative physiology and growth of two perennial tussock grass species in a semi-arid environment’, Annals of Botany, vol. 77, no. 1, pp. 81-86, CAB Abstracts.

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.