Descurainia (Descurainia sophia)

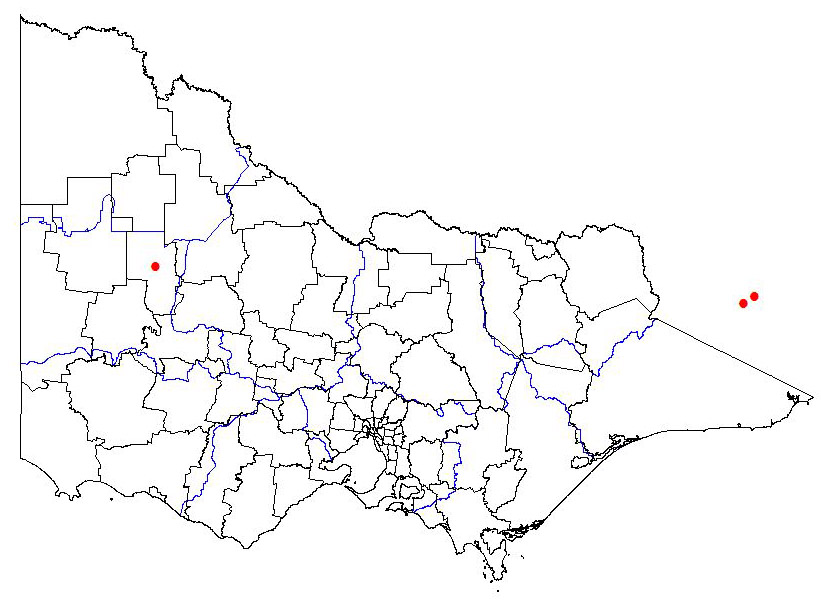

Present distribution

|  Map showing the present distribution of this weed. | ||||

| Habitat: “Flixweed … inhabits agricultural land and other disturbed areas. … throughout California to about 8500 feet (2600 m) … roadsides, fields, vineyards, orchards, agronomic crop fields, gardens, disturbed desert areas, canyon bottoms, and disturbed, unmanaged places. …” (University of California Online 2010) | |||||

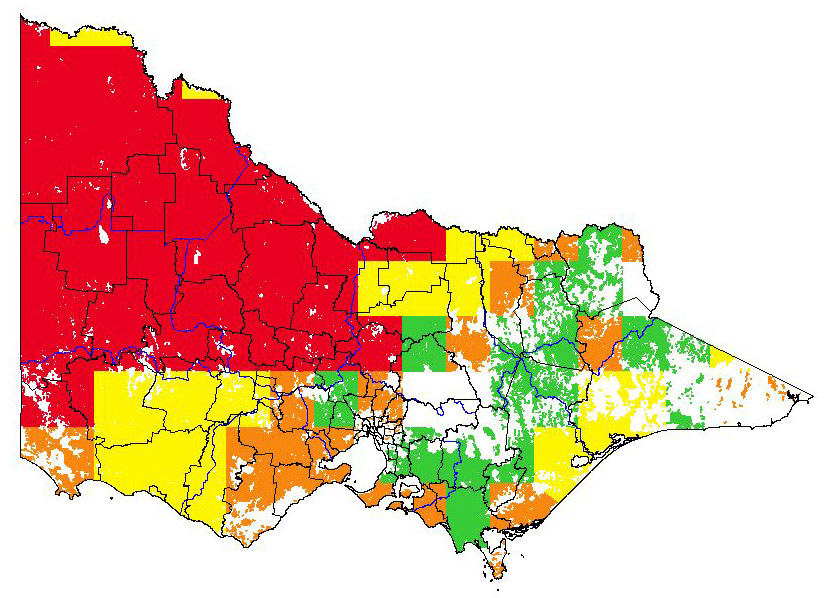

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Broadacre cropping; horticulture perennial; horticulture seasonal; pasture dryland; pasture irrigation Ecological Vegetation Divisions Foothills forest; high altitude shrubland/woodland; alpine treeless; granitic hillslopes; rocky outcrop shrubland; western plains woodland; basalt grassland; alluvial plains grassland; semi-arid woodland; alluvial plains woodland; ironbark/box; chenopod shrubland; chenopod mallee; hummock-grass mallee; lowan mallee; broombush whipstick Colours indicate possibility of Descurainia sophia infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Erect stems are 0.3 – 1 m tall (MAFRI 2010; University of California Online 2010). Therefore, if weed in dense enough growth, impede pedestrian access. | ML | ML |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | Erect stems are 0.3 – 1 m tall (MAFRI 2010; University of California Online 2010). Therefore, if weed in dense enough growth, some recreational uses would be affected. | MH | ML |

| 3. Injurious to people? | D. sophia used by Native Americans for a wide range of uses. These include: toothache remedy, dermatological aid, veterinary aid, fodder, beverage, in bread & cakes, ice cream, soup, a winter use food (staple, dried food), a preservative, and a fertiliser (University of Michigan 2010). D. sophia used in Syria to treat medical ailments, such as; bronchitis, cough, dysentery, fever, vermifuge (Dr Duke’s Ethnobotany website 2010). No adverse affects listed amongst ethnobotanical uses. | L | ML |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | None listed in literature reviewed. | L | L |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Weed of arid and semi-arid regions; does not like wet conditions. Therefore water issues unlikely. | L | L |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Weed of arid and semi-arid regions; does not like wet conditions. Therefore water issues unlikely. | L | L |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | None listed in literature reviewed. | L | L |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | Dense monocultures of weed incursions not mentioned in literature reviewed | L | L |

| 9. Change fire regime? | None listed in literature reviewed. | L | L |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC = Plains Grassy Woodland (E); CMA = Glenelg Hopkins; Bioregion = Dundas Tablelands; VH CLIMATE potential. D. sophia is described as “highly competitive to desirable plant species” (MAFRI 2010). “Overwintered rosettes are strong competitors … spring-emerging flixweed seedlings do not compete as well, especially in heavy crop stands.” (Government of Alberta 2010). Major displacement of some dominant spp. within a strata/layer (or some dominant spp. within different layers). | MH | M |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC = Riparian Chenopod Woodland (D); CMA = Mallee; Bioregion = Lowan Mallee; VH CLIMATE potential. D. sophia is described as “highly competitive to desirable plant species” (MAFRI 2010). “Overwintered rosettes are strong competitors … spring-emerging flixweed seedlings do not compete as well, especially in heavy crop stands.” (Government of Alberta 2010). Major displacement of some dominant spp. within a strata/layer (or some dominant spp. within different layers). | MH | M |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC = Sandstone Ridge Shrubland (LC); CMA = Wimmera; Bioregion = Goldfields; VH CLIMATE potential. D. sophia is described as “highly competitive to desirable plant species” (MAFRI 2010). “Overwintered rosettes are strong competitors … spring-emerging flixweed seedlings do not compete as well, especially in heavy crop stands.” (Government of Alberta 2010). Major displacement of some dominant spp. within a strata/layer (or some dominant spp. within different layers). | MH | M |

| 11. Impact on structure? | D. sophia is described as “highly competitive to desirable plant species” (MAFRI 2010). “Overwintered rosettes are strong competitors … spring-emerging flixweed seedlings do not compete as well, especially in heavy crop stands.” (Government of Alberta 2010). Minor effect on >60% of the layers or major effect on < 60% of the floral strata. | MH | M |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | None listed in literature reviewed. | L | L |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | None listed in literature reviewed. However, as “flixweed can be fatally toxic to cattle when the flowering plants are consumed in quantity (University of California Online 2010); and “… all parts of the plant have been found to be somewhat toxic to livestock, especially horses and cattle (sheep and goats are more tolerant)…” (Hilty 2003 – 2010); D. sophia MAY be toxic to some threatened fauna. | L | L |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | None listed in literature reviewed. However, as “flixweed can be fatally toxic to cattle when the flowering plants are consumed in quantity (University of California Online 2010); and “… all parts of the plant have been found to be somewhat toxic to livestock, especially horses and cattle (sheep and goats are more tolerant)…” (Hilty 2003 – 2010); D. sophia MAY be toxic to some threatened fauna. | L | L |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera) has a food preference for D. sophia (Sarfraz et al. 2010). Eggs deposited on, and pupae ate, D. sophia (ibid.). Eggs of Ceutorhynchus subpubescens LeConte (Coleoptera) laid into the apical stem regions of D. sophia (Dosdall et al. 2007). D. sophia is described as a “spring food source for flea beetles” (MAFRI 2010). “… nectar and pollen … attract flower flies … catepillars of the butterflies Pieris rapae (Cabbage White), Pontia protodice (Checkered White), and Anthocharis midea (Falcate Orangetip) feed on the foliage.” (Hilty 2003 – 2010) … seedpods are eaten by various species of quail and the foliage is eaten sparingly by bighorn sheep, elk, and mule deer…” (ibid.). MAY provide alternate food source for indigenous fauna. | MH | M |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | “Flixweed can be fatally toxic to cattle when the flowering plants are consumed in quantity (University of California Online 2010). “… all parts of the plant have been found to be somewhat toxic to livestock, especially horses and cattle (sheep and goats are more tolerant)…” (Hilty 2003 – 2010). Toxic. | H | ML |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera) has a food preference for D. sophia (Sarfraz et al. 2010). Eggs deposited on, and pupae ate, D. sophia (ibid.). Eggs of Ceutorhynchus subpubescens LeConte (Coleoptera) laid into the apical stem regions of D. sophia (Dosdall et al. 2007). D. sophia is described as a “spring food source for flea beetles” (MAFRI 2010). “… nectar and pollen … attract flower flies … catepillars of the butterflies Pieris rapae (Cabbage White), Pontia protodice (Checkered White), and Anthocharis midea (Falcate Orangetip) feed on the foliage.” (Hilty 2003 – 2010) … seedpods are eaten by various species of quail and the foliage is eaten sparingly by bighorn sheep, elk, and mule deer…” (ibid.). MAY provide food for minor pest species. | ML | M |

| 18. Provides harbor? | Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera) has a food preference for D. sophia (Sarfraz et al. 2010). Eggs deposited on, and pupae ate, D. sophia (ibid.). Eggs of Ceutorhynchus subpubescens LeConte (Coleoptera) laid into the apical stem regions of D. sophia (Dosdall et al. 2007) Contarinia nasturtii (swede midge) (Diptera) were reported as laying eggs on D. sophia, but not feeding off it (Hallett 2007). MAY provide harbour for minor pest animal. | ML | M |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | “Flixweed is one of the three most troublesome annual dicot weeds in Chinese wheat fields …” (Cui et al. 2008). “Flixweed is known to reduce wheat yield in China” (Shi and Che 1993 In: Cui et al. 2008). D. sophia “May reduce the yield of economically important plant species by competition” (MAFRI 2010). “Flixweed can be fatally toxic to cattle when the flowering plants are consumed in quantity (University of California Online 2010). | H | H |

| 20. Impact quality? | “Flixweed is one of the three most troublesome annual dicot weeds in Chinese wheat fields …” (Cui et al. 2008). D. sophia is a “… source of impurity in cereal and forage seed” (MAFRI 2010). “Seed has been found as an impurity in cereal and forage crops …” (Organic Weeds UK 2007). | MH | H |

| 21. Affect land value? | “Flixweed is one of the three most troublesome annual dicot weeds in Chinese wheat fields …” (Cui et al. 2008). “Flixweed is known to reduce wheat yield in China” (Shi and Che 1993 In: Cui et al. 2008). D. sophia “May reduce the yield of economically important plant species by competition. A source of impurity in cereal and forage seed” (MAFRI 2010). “Flixweed can be fatally toxic to cattle when the flowering plants are consumed in quantity (University of California Online 2010). | M | M |

| 22. Change land use? | “Flixweed is one of the three most troublesome annual dicot weeds in Chinese wheat fields …” (Cui et al. 2008). “Flixweed is known to reduce wheat yield in China” (Shi and Che 1993 In: Cui et al. 2008). D. sophia “May reduce the yield of economically important plant species by competition. A source of impurity in cereal and forage seed” (MAFRI 2010). “Flixweed can be fatally toxic to cattle when the flowering plants are consumed in quantity (University of California Online 2010). | ML | M |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | “Flixweed is one of the three most troublesome annual dicot weeds in Chinese wheat fields …” (Cui et al. 2008). “Flixweed is known to reduce wheat yield in China.” (Shi and Che 1993 In: Cui et al. 2008) “Seed has been found as an impurity in cereal and forage crops …” (Organic Weeds UK 2007). | M | H |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera) has a food preference for D. sophia (Sarfraz et al. 2010). Eggs deposited on, and pupae ate, D. sophia (ibid.). Eggs of Ceutorhynchus subpubescens LeConte (Coleoptera) laid into the apical stem regions of D. sophia (Dosdall et al. 2007) Contarinia nasturtii (swede midge) (Diptera) were reported as laying eggs on D. sophia, but not feeding off it (Hallett 2007). | M | M |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | “Seed germination only occurs in the light … in spring and autumn …” (Organic Weeds UK 2007). “Nitrate promotes germination …” (ibid.) Requires natural seasonal disturbances such as seasonal rainfall, spring/summer temperatures for germination | MH | ML |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | “… flourishes in full sun, mesic to dry conditions … any kind of soil’ (Hilty 2003 – 2010) [ie. not wet conditions]. Requires more specific requirements to establish (eg. open space or bare ground with access to light and direct rainfall). | ML | ML |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | “Flixweed … inhabits agricultural land and other disturbed areas. … roadsides, fields, vineyards, orchards, agronomic crop fields, gardens, disturbed desert areas, canyon bottoms, and disturbed, unmanaged places” (University of California Online 2010). “… scrub, grassland, woodland …” (Cal-IPC 2006) “… Where found: Disturbed, cultivated or waste ground …” (Kershaw et al. 1998) “… growing in waste places, fields, roadsides and other disturbed sites.” (Whitson et al. 1992) D. sophia “prefers disturbed areas …” (Hilty 2003 – 2010). Establishes in highly disturbed natural ecosystems (eg. roadsides, wildlife corridors, or areas which have a greater impact by humans such as tourist areas or campsites) or in overgrazed pastures/poorly growing or patchy crops. | ML | M |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | “Flixweed … [is an] annual dicot …” (Cui et al. 2008) annual herb (Kershaw et al. 1998) “…annual or biennial …” (University of California Online 2010). | L | H |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | None mentioned in literature reviewed. | L | L |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Although grazing by various herbivores was mentioned throughout the reviewed literature, it was regularly referred to as light grazing. Thus, it does not seem that grazing of D. sophia is heavy enough to warrant pressure on its populations. Consumed but non-preferred or consumed but recovers quickly; capable of flowering /seed production under moderate herbivory pressure. | MH | L |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | D. sophia is described as a “vigorous plant” (MAFRI 2010). Rapid growth rate that will exceed most other species of the same life form. | H | L |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Found in arid areas (Randall 2002). “… flourishes in … mesic to dry conditions …’ (Hilty 2003 – 2010) [ie. not wet conditions]. May be tolerant of one stress, susceptible to at least two. | L | MH |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | Reproduces by seed (University of California Online 2010). “… spreads by seeds …” (Whitson et al. 1992) “…seeds are small enough to be blown about by the wind … seeds become sticky when wet, and may be carried about in the feathers of birds, fur of animals, or shoes of humans…” (Hilty 2003 – 2010). Sexual. | L | MH |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | “… average seed number per plant … 6,000 – 75,650. A large plant can produce 700,000 seeds …” (Organic Weeds UK 2007). Bond et al. cite the following: “… under optimal conditions … it produces 4,000 to 7,500 seeds per plant (Mahn 1988)”; “… Average seed number per plant … 75,650 (Rich 1991)”; “… 6,000 …” (Stevens 1957); “… average seed number per plant in ruderal situations … 52,636 (Pawlowski et al. 1967). …” “There are roughly ten to twenty seeds per pod …” (University of California Online 2010). “… 1 row of … more than 20 seeds …” (Kershaw et al. 1998). Greater than 2,000. | H | H |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | 2 – 5% seed viable after 9.7 years after burial (Conn et al. 2006). “… Seeds can survive in the soil for more than three years.” (Government of Alberta 2010). Greater than 25% of seeds survive 5-10 years in the soil, or lower viability but survive 10-20 years. | ML | H |

| 12. Reproductive period? | “Flixweed … [is an] annual or biennial (University of California Online 2010), therefore the annuals must set seed within one year, whilst the biennials seed for a couple of years. Mature plant produces viable propagules for only 1–2 years. | ML | M |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | “Flixweed … [is an] annual or biennial (University of California Online 2010), therefore the annuals must set seed within one year, whilst the biennials seed for a couple of years. Reaches maturity and produces viable propagules in under a year. | H | M |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Seeds “… become sticky when moistened …” (University of California Online 2010). “…abundant seed, which can be spread by soil or water movement, and by clinging to animals, humans and vehicle tires …” (Cal-IPC 2006-’10). Very light, wind dispersed seeds, or bird dispersed seeds. | H | M |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | As the “seeds are small enough to be blown about by the wind …” (Hilty 2003 – 2010), combined by the numerous means of dispersal, it is very likely that at least one seed disperses greater than one kilometre. | H | ML |

References

Bond W, Davies G, and Turner R. (2007) The Biology and Non-chemical Control of Flixweed (Descurainia sophia (L.) Webb ex Prantl.). The Organic Organisation. Available at http://www.gardenorganic.org.uk/organicweeds/downloads/descurainia%20sophia.pdf (verified 24 June 2010).

California Invasive Plant Council (Cal-IPC). (2006) California Invasive Plant Inventory. Cal_IPC, Berkeley. Also available at www.cal-ipc.org (verified 24 June, 2010).

California Invasive Plant Council (Cal-IPC). (2006 – ’10) Descurainia sophia webpage. Available at http://www.cal-ipc.org/ip/management/plant_profiles/Descurainia_sophia.php (verified 24 June 2010).

Conn JS, Beattie KL, and Blanchard A. (2006) “Seed Viability and Dormancy of 17 Weed Species After 19.7 Years of Burial in Alaska.” In: Weed Science. 54:464 – 470.

Cui HL, Zhang CX, Zhang HJ, Liu X, Liu Y, Wang GQ, Huang HJ, and Wei SH. (2008) “Confirmation of Flixweed (Descurainia sophia) Resistance to Tribenuron in China.” In: Weed Science. 56: 775 – 779.

Dosdall LM, Ulmer BJ, and Bouchard P. (2007) “Life History, Larval Morphology, and Nearctic Distribution of Ceutorhynchus subpubescens (Coleoptera: Curculionidae).” In: Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 100 (2): 178 – 186.

Dr Duke’s Ethnobotany Website. (2010) Ethnobotanical Uses of Descurainia Sophia (BRASSICACEAE) page. Available at http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgibin/duke/ethnobot.pl?ethnobot.taxon=Descurainia%20sophia

Government of Alberta. (2010) Agriculture and Rural Development. Flixweed webpage. Available at http://www1.agric.gov.ab.ca/$department/deptdocs.nsf/all/prm2589 (verified 24 June 2010).

Hallett RH. (2007) “Host Plant Susceptibility to the Swede Midge (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae).” In: Journal of Economic Entomology. 100 (4): 1335 – 1343.

Hilty J. (2003 – 2010) Weedy Wildflowers of Illinois. Flixweed webpage. Available at http://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/weeds/plants/flixweed.htm (verified 24 June 2010).

Kershaw L, MacKinnon A, and Pojar J. (1998) Plants of the Rocky Mountains. Lone Pine Publishing, Edmonton and Auburn.

Mahn EG. (1988) “Changes in the Structure of Weed Communities Affected by Agro-chemicals – What Role Does Nitrogen Play?” In: Ecological Bulletins. 39: 71 – 73.

Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives (MAFRI). (2010) Flixweed webpage. Available at http://www.gov.mb.ca/agriculture/crops/weeds/fab52s00 (verified 11 May,

2010).

Organic Weeds UK. (2007) Organic Weed Management. Flixweed webpage. Available at http://www.gardenorganic.org.uk/organicweeds/weed_information/weed.php?id=57 (verified 24 June 2010).

Pawlowski F, Kapeluszny J, Kolasa A, and Lecyk Z. (1967) “Fertility of some Species of Ruderal Weeds.” In: Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie – Sklodowska Lublin-Polonia. 22 (15): 221 – 231.

Randall R. (2002) A Global Compendium of Weeds. RG and FJ Richardson, Melbourne.

Rich TCG. (1991) “Crucifers of Great Britain and Ireland.” In: BSBI Handbook No. 6. Botanical Society of the British Isles.

Sarfraz RM, Dosdall LM, and Keddie BA. (2010) “Performance of the Specialist Herbivore Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) on Brassicaceae and non-Brassicaceae Species.” In: Canadian Entomology. 142: 24 – 35.

Shi CX and Che JY. (1993) “Studies on Wheat Yield Loss Caused by Flixweed (Descurainia sophia).” In: Shaanxi Journal of Agricultural Science. 3: 21 – 23. [in Chinese]

Stevens OA. (1957) “Weights of Seeds and Numbers per Plant.” In: Weeds. 5: 46 – 55.

University of California Online. (2010) How To Manage Pests: Flixweed webpage. Available at http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/WEEDS/flixweed.html (verified 11 May,

2010).

University of Michigan. (2010) Native American Ethnobotany. Descurainia sophia webpage. University of Michigan. Available at http://herb.umd.umich.edu/herb/search.pl

(verified 02 June 2010).

Walsh N and Stajsic V. (2007) A Census of the Vascular Plants of Victoria. 8th Edn. Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne.

Whitson TD (Editor), Burrill LC, Dewey SA, Cudney DW, Nelson BE, Lee RD, and Parker R. (1992) Weeds of the West. Revised Edition. The Western Society of Weed Science, Newark.

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) (2010) Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, Available at

http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/ (verified 11 May, 2010).

Calflora: Information on California plants for education, research and conservation. [web application]. (2010) Berkeley, California: The Calflora Database [a non-profit

organization]. Available at http://www.calflora.org/ (verified 11 May, 2010).

Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) (2006) Flora information system [CD-ROM], Biodiversity and Natural Resources Section, Viridans Pty Ltd, Bentleigh.

Department of the Environment and Heritage (Commonwealth of Australia). (1993 – On-going) Australian Plant Name Index (APNI) http://www.cpbr.gov.au/apni/index.html (verified 11 May, 2010).

EIS: Environmental Information System (2006) Parks Victoria.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) (2010) Global biodiversity information facility, Available at http://www.gbif.org/ (verified 11 May, 2010).

Integrated Taxonomic Information System. (2010) Available at http://www.itis.gov/ (verified 11 May, 2010).

IPMS: Integrated Pest Management System (2006) Department of Primary Industries.

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) (2010) w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, Available at http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html (verified 11 May, 2010).

National Biodiversity Network (2004) NBN Gateway, National Biodiversity Network, UK, Available at http://www.searchnbn.net/index_homepage/index.jsp (verified 11 May,

2010).

United States Department of Agriculture. (2009) Agricultural Research Service, National Genetic Resources Program. Germplasm Resources Information Network - (GRIN) [Online Database]. Taxonomy Query. Available at http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/taxgenform.pl (verified 11 May, 2010).

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.