Sage leaved rockrose (Cistus salviifolius)

Present distribution

|  Map showing the present distribution of this weed. | ||||

| Habitat: Native to Southern Europe, Northern Africa and Western Asia. Reported from coastal, to arid and mountain areas, in fire prone forest, scrubland and invading in grassland. | |||||

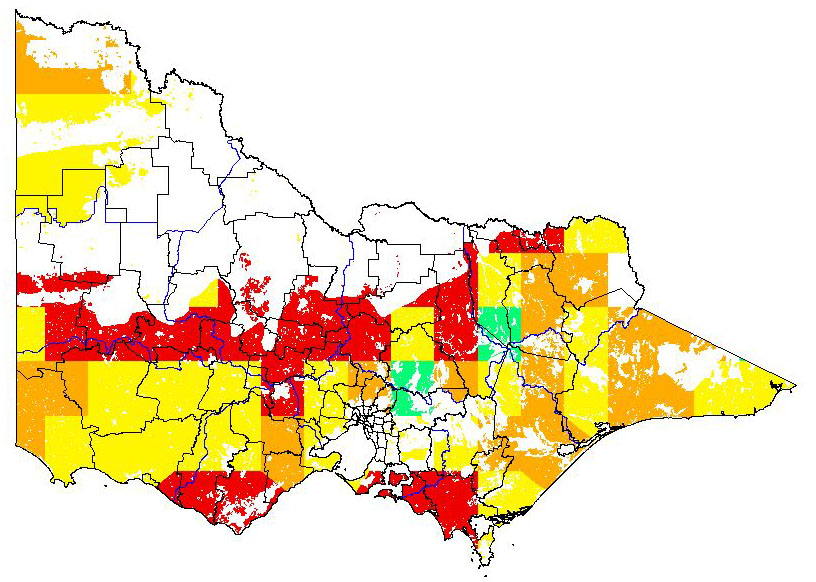

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Forest private plantation; forest public plantation; pasture dryland. Broad vegetation types Coastal scrubs and grassland; coastal grassy woodland; heathy woodland; lowland forest; heath; box ironbark forest; inland slopes and plains; sedge rich woodland; dry foothills forest; montane dry woodland; sub-alpine woodland; grassland; plains grassy woodland; valley grassy forest; herb-rich woodland; sub-alpine grassy woodland; montane grassy woodland; rainshadow woodland; mallee; mallee heath; boinka-raak; mallee woodland; wimmera / mallee woodland Colours indicate possibility of Cistus salviifoliu infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Can form dense stands, some nuisance factor. | ml | m |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | planted as an ornamental | ml | m |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Species of the genus linked with dermatitis and has caused illness if consumed in large amounts by animals, yet unknown full effect of chemical composition however only appears mildly toxic. | ml | m |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | No structural damage reported, attempts of control reported at the Clunes cemetery, therefore must have some aesthetic issues (Clarke 2005). | ml | m |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | terrestrial species | l | m |

| 6. Impact water quality? | terrestrial species | l | m |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | Has been used for erosion control, however its need for fire for regeneration would leave the soil exposed for a time (Guven 1985). | ml | m |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | A successful competitor. | ml | m |

| 9. Change fire regime? | Found to be only moderately flammable in comparison with other Mediterranean species (Dimitrakopoulos 2001), however its requirement of fire for regeneration and pre-drought leaf fall may alter Australian fire condition (Thanos & Georghiou 1988). | ml | m |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC= Plains Savannah (E); CMA= Wimmera; Bioreg= Lowan Mallee; VH CLIMATE potential. Can become dominant leading to lower floral diversity especially in the herb layer. Major displacement of dominant sp. within a layer. | mh | mh |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC= Semi-arid Woodland (D); CMA= Wimmera; Bioreg= Lowan Mallee; VH CLIMATE potential. Can become dominant leading to lower floral diversity especially in the herb layer. Major displacement of dominant sp. within a layer. | mh | mh |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC= Heathy Woodland (LC); CMA= Wimmera; Bioreg= Lowan Mallee; VH CLIMATE potential. Can become dominant leading to lower floral diversity especially in the herb layer. Major displacement of dominant sp. within a layer. | mh | mh |

| 11. Impact on structure? | Has prevented the natural regeneration of cork oak (Sebei etal 2001), can form dense scrub immediately after fire, reducing floral diversity especially in the first few years after fire (Tavsanoglu, Kaynas & Gurkan 2002). | mh | mh |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | No specific data, however if able to prevent the regeneration of a tree species and reduce the overall floral diversity could easily have some impact. | mh | ml |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | No specific data, however has been reputedly been linked with illness’ and disorders in sheep and cattle when forced to be a major component of the diet (Bruno-Soares, Abreu & Soler 2004 and Lima etal 2003). | mh | m |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | If large part of diet has been linked with illness and death in sheep and cattle. And in competing with other species reduces potential natural sources of food and shelter (Bruno-Soares, Abreu & Soler 2004 and Lima etal 2003). | m | m |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | Flowers visited by numerous insects (Clarke 2005). | mh | m |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | If large part of diet has been linked with illness and death in sheep and cattle (Bruno-Soares, Abreu & Soler 2004 and Lima etal 2003). | ml | mh |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | Is eaten by goats and deer but not preferred and flowers a nectar source for bees (Clarke 2005, Gomez Castro etal 1989 and Maillard & Casanova 1994). | ml | m |

| 18. Provides harbour? | No more than any other shrub species. | m | m |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | Has been linked with death of cattle and illness in other stock species (Bruno-Soares, Abreu & Soler 2004 and Lima etal 2003). | mh | mh |

| 20. Impact quality? | Can cause illness and weight loss in stock (Bruno-Soares, Abreu & Soler 2004 and Lima etal 2003). | ml | mh |

| 21. Affect land value? | No specific data, can be controlled. | l | l |

| 22. Change land use? | Can be controlled, illness in cattle also contributed to lack of other feed, not a suitable browse species during drought periods (Bruno-Soares, Abreu & Soler 2004 and Lima etal 2003). | ml | m |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | If cause illness may increase veterinary costs, also the cost of control. | mh | m |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Not specified. | l | m |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | Majority of seed produced has an induced dormancy due to a hard shell coat and germinate after fire, however an estimated 25% of seed produced can germinate the following winter (Thanos & Georghiou 1988). | mh | h |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | It has been shown that there are no light restrictions on the germination of cistus seeds (Thanos & Georghiou 1988), however they are inhabitants of dry scrub and open woodland and colonists after fire suggesting that seedlings can only establish under moderate to no cover (Clarke 2005). | mh | mh |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Require fire for mass germination, Inhabit open woodland (Clarke 2005). | mh | mh |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Small shrub (Clarke 2005). | l | mh |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | None described however does have a complex chemical composition and C. ladanifer has been shown to have allelopathic properties. | l | l |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Can be eaten by goats and deer but not preferred (Gomez Castro etal 1989 and Maillard & Casanova 1994). | mh | mh |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Has been chosen for use for erosion control over other slower growing shrub species (Guven 1985). | mh | m |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Fire kills the plant but is a requirement for mass germination and effective regeneration of the species (Thanos & Georghiou 1988). Semi-deciduous having leaf fall pre-drought conditions allows the plant to successfully deal with water stress (Thanos & Georghiou 1988) . Described as being tolerant of winter stress of northern Spain, presume this includes frost tolerance (Garcia-Plazaola, Hernandez & Becerril 2000). Described only in dry sites, possible susceptibility to waterlogging. | mh | mh |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | Produces seed, but is self-incompatible (Herrera 1992). | l | h |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | Not directly specified however species of this genus have been reported to produce between 3000 to 200000 seeds per annum (Talavera, Gibbs & Herrera 1993). | h | m |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | Approximately 25% of seeds produces will germinate the next winter, however the rest have a hard seed coat, which requires fire or some other form of scarification for germination, till then they remain dormant, approximately 10+years ((Ferrandis etal 1999 and Thanos & Georghiou 1988). | mh | m |

| 12. Reproductive period? | Maturity in this genus is reach at approximately 2-3 years and live upwards of 15 years therefore 10+ years of reproduction. | h | m |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | Shrub not reported flowering before the second year. | ml | m |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | May potentially be transported externally on animals, however thought largely by water and gravity (Clarke 2005 and Farley & McNeilly 2000). | ml | m |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | Not thought to regularly be dispersed more than the immediate surroundings of the maternal plant (Farley & McNeilly 2000). | ml | m |

References

Bruno-Soares. A. M., Abreu. J. M. & Soler. F. (2004) Preliminary in vitro studies of Cistus salvifolius leaves in relation to metabolic disorders in sheep.. Acamovic. T. Stewart. C.S. & Pennycott. T.W. (Eds) Poisonous plants and related toxins. CABI Publishing. Wallingford. UK.

Clarke. E. (2005) ‘Wild’ Cistus L. (CISTACEAE) in Victoria- future problem weeds or benign escapees from cultivation? Muelleria. 21: 77-86.

Dimitrakopoulos A.P. (2001) A statistical classification of Mediterranean species based on their flammability components. International Journal of Wildland Fire. 10: 113-118.

Farley. R.A. & McNeilly. T. (2000) Diversity and divergence in Cistus salvifolius (L.) populations from contrasting habitats. Hereditas. 132: 183-192.

Ferrandis. P., Martinez-Sanchez. J.J., Agudo. A., Cano. A.L., Gallar. J.J. & Herranz. J.M. (1999) Presence of Cistus species (Cistaceae) in the soil seed bank os a grassland in the rana formation of Cabaneros National Park. [Spanish] Investigation Agraria, Sistemas y Recursos Forestales. 8: 361-376.

Garcia-Plazaola. J.L., Hernandez. A. & Becerril. J.M. (2000) Photoprotective responses to winter stress in evergreen Mediterranean ecosystems. Plant Biology. 2: 530-535.

Gomez Castro. A.G., Sanchez Rodriguez. M., Peinado Lucena. E., Mata Moreno. C., Domenech Garcia. V. & Megias Rivas. D. (1989) Intake of Cistus by milking goats grazing in semiextensive conditions. [Spanish] Revista Pastos. 18-19: 1-2, 29-43.

Guven. M.A. (1985) Landscape reclamation affairs in highway slope stabilisation and determination of suitable plants for this purpose in Aegean region. Ege Universitesi ziraat Fakultesi Dergisi. 22: 117-129.

Herrera. J. (1992) Flower variation and breeding systems in the Cistaceae. Plant systematics and evolution. 179: 245-255.

Lima. M.s. Peleteiro. M.C., Malta. M., Paris. A.B. & Hjerpe. C.A. (2003) Urinary tract disease, weight loss and death possibly related to winter browsing of a shrubby plant (Cistus salviifolius) in three herds of Portuguese beef cattle. Bovine Practitioner. 37: 162-178.

Maillard. D. & Casanova. J.B. (1994) Palatability of trees, shrubs and brushes to Corsican red deer. [French] Mammalia. 58: 371-381.

Sebei. H., Albouchi. A., Rapp. M. & El-Aouni. M.H. ( 2001) Evaluation of aboveground and below ground biomass in a sequence of degraded Cytisus sp. cork oak forests in Kroumirie. Tunisia. [French]. Annals of forest Science. 58: 175-191.

Talavera. S., Gibbs. P.E. & Herrera. J. (1993) Reproductive biology of Cistus ladanifer (Cistaceae). Plant Systematics and Evolution. 186: 123-134.

Tavsanoglu. C., Kaynas. B.Y. & Gurkan. B. (2002) Plant Species Diversity in a post-fire successional gradient in Marmaris National Park, Turkey. Forest fire research and wildland fire safety: Proceedings of IV International Conference on Forest Fire Research. Viegas. D.X. (Ed)

Thanos. C.A. & Georghiou. K. (1988) Ecophysiology of Fire-stimulated seed germination in Cistus incanus ssp. Creticus (L.) Heywood and C. salvifolius L. Plant, Cell and Environment. 11: 841-849.

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) 2006, Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, viewed, 28 Aug. 2006, http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/

Borghetti. M., Magnani. F., Fabrizio. A. & Saracino. A. (2004) Facing drought in a Mediterranean post-fire community: tissue water relations in species with different life traits. Acta Oecologica. 25: 67-72.

Calflora: Information on California plants for education, research and conservation. [web application]. 2006. Berkeley, California: The Calflora Database [a non-profit organization]. Available: http://www.calflora.org/ . (Accesses: 28 Aug 2006)

Clarke. E. (2005) ‘Wild’ Cistus L. (CISTACEAE) in Victoria- future problem weeds or benign escapees from cultivation? Muelleria. 21: 77-86.

Farley. R.A. & McNeilly. T. (2000) Diversity and divergence in Cistus salvifolius (L.) populations from contrasting habitats. Hereditas. 132: 183-192.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2006, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed 28 Aug 2006, http://www.gbif.org/

Moretti. M., Conedera. M., Moresi. R. & Guisan. A. (2006) Modelling the influence of change in fire regime on the local distribution of a Mediterranean pyrophytic plant species (Cistus salviifolius) at its northern range limit. Journal of Biogeography. 33: 1492-1502.

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.