Invasive Plants Glossary

Agricultural Weeds

Agricultural weeds threaten crops, horticulture and pasture production, and can be toxic to humans and stock. They may be declared noxious weeds. It has been estimated, for example, that Ragwort costs Victorian dairy industry $1.6 million/annum in lost milk production due to milk tainting when eaten by stock (McClaren, 1996). Saffron thistle, as another example, covers areas of central and north-eastern Victoria - and was estimated to have covered approximately 4.2 million hectares in 1990 (Lane et al, 1990). It competes with, restricts or eliminates pasture species on low fertility soils thereby reducing carrying capacity.

| The purple flowers of Paterson's Curse are evident from the air in pastures near Melbourne. Once established Paterson's Curse can compete strongly with pasture species. It also contains an accumulative poison which may cause chronic liver damage to stock although they will usually avoid it if other green feed is available. |

Declared Noxious Weeds

Declared noxious weeds (DNW) in Victoria are plants that have been proclaimed under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 which requires landholders to control and eradicate these weeds. These plants cause environmental or economic harm or have the potential to cause such harm. There are four categories of noxious weeds defined under the CALP Act 1994: State Prohibited, Regionally Prohibited, Regionally Controlled and Regionally Restricted.

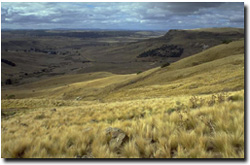

| Serrated Tussock is a Declared Noxious Weed in Victoria and results in severe reductions in paddock carrying capacities. The plant is indigestible to stock. The picture shows part of the Parwan catchment to the northwest of Melbourne - which has been heavily infested with Serrated Tussock. |  |

Environmental Weeds

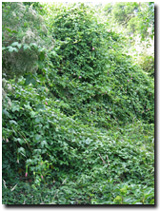

Environmental weeds are weeds that threaten natural ecosytems (e.g. reduce biodiversity). They are capable of invading native plant communities and out-competing native species - resulting in a reduction of plant diversity and loss of habitat for native fauna. Along roadsides, for example, grassy weeds can threaten native grassland remnants that provide important habitat for endangered native species. Phalaris (also known as Toowoomba Canary Grass), for example, is a major problem on roadsides where it can overwhelm native vegetation to the detriment of endangered native bird species such as the Grey-crowned Babbler (Pomatastomus temporali) (Robinson et al, 1997). Willow trees along stream sides and waterways can eliminate native vegetation, change water flows, increase bank erosion, and destroy habitat for native species. In forests, vines (such as Bridal Creeper) smother native plants, resulting in a loss of understorey vegetation (ENRC 1998).

Environmental weeds can also be declared noxious weeds (e.g. Blackberry and Boneseed). However, a number of serious environmental weeds are not included in the Schedules of the Catchment and Land Protection Act. Weeds of natural ecosystems can also be other native species that are not local (indigenous) to an area but have potential to damage the local plant community (eg., Sweet Pittosporum).

| Photo on Left: Banana passionfruit is an environmental weed that is capable of smothering native vegetation with its dense growth of leafy vines and preventing recruitment. Banana passionfruit originated from Andean valleys in South America. Photo on Right: The banana passionfruit has an attractive flower and has been grown as an ornamental creeper in gardens. However, it's fruit can be easily dispersed (by birds, humans or possums). |  |

Local Priority Weeds

These are weeds that are widespread within a Catchment Management Authority (CMA) region, but management of infestations is undertaken at a local level where control is deemed appropriate. Such management efforts are strongly supported through community involvement (e.g. Landcare). (Note: this status only has relevance within a CMA region and has no legal standing).

Mapping Potential Distribution of Weeds

Maps of the potential distribution of weed species in Victoria on this website have been developed as part of the 'Pest Plants Invasiveness Assessment' led by John Weiss (former DPI, Frankston). For further details refer to the downloadable report on this site.

Information on Australian and overseas distributions were imported into a climate matching program, CLIMATE®, to predict potential distribution in Australia. Using the localities where a species occurs overseas and within Australia, the potential climatic range of any species can be overlaid upon Australia's climatic regions. The map below, for example, illustrate the climatic regions most suitable for Spartina in Victoria.

Potential distribution of Spartina anglica (left) and S. x townsendii (right) in Victoria, according to climatic parameters. (Areas in red indicate a 80%+ match with the preferred climate of the plant species, yellow 70%, orange 60% and green 50%). |

The 16 climatic parameters that are used to determine potential distribution can be grouped into temperature or rainfall parameters.

Aquatic weeds are modelled for potential climatic range slightly differently than terrestrial species. Rainfall is obviously not a major criterion for determining the potential range of aquatic species, especially submergents, although it may play a key role in triggering certain biological properties (e.g. freshwater flood events appear to stimulate flowering in Spartina) (Strong pers. comm.). Thus rainfall parameters are excluded when predicting the climatic range. Water temperature is generally more moderate and has fewer fluctuations than air temperature and provides a more accurate prediction for modelling aquatic species. However, the required data is usually unknown. Therefore, modelling the climatic range of aquatic species has included eight air temperature parameters that provide at least some indication of potential range. The process is, consequently, more uncertain and likely to overestimate the species’ actual potential range.

Dialogue box from CLIMATE® showing the climatic parameters used in terrestrial weed modelling.

The eight rainfall parameters are not included when modelling the potential climatic range of aquatic weeds.

The climatic overlays are then used to determine the potential range of the plant species by linking or intersecting them with susceptible land uses and broad vegetation types (BVTs) or wetlands using a Geographic Information System (GIS) program. This refines the potential distribution maps produced using the climate matching program, as plants are limited by other factors, such as disturbance regimes associated with land uses. The resulting maps illustrate the potential range of Spartina in Victoria.

Potential distribution of Spartina anglica (left) and S. x townsendii (right) in Victoria, according to climatic parameters, susceptible land uses and BVTs.

Areas in red indicate a very high probability that Spartina could establish in watercourses and wetlands within this region, yellow a high, and orange a medium probability of establishment.

Potential distribution of Spartina anglica and S. x townsendii in Eastern Victoria, according to climatic parameters, susceptible land uses and BVTs.

The potential distribution maps are estimates and are only as reliable as the data they are based on. As more records are collected on where the plants occur, the predictions will become more accurate. It is expected, consequently, that there are potential distribution maps that do not yet fully represent existing or potential distribution. Also, for some species there may be insufficient data to undertake potential distribution mapping. For instance, only a small number of current distribution records were found for Salix x rubens; too few to produce a meaningful potential distribution map. For these species, a provisional coarse climate map is produced but the next stage of matching onto susceptible land types is not completed.

The present distribution of weeds is generally under represented in the databases used (i.e. herbarium records, Wild Plants of Victoria (Viridans 1999), and to a lesser extent IPMS/PMIS), with the exception of priority weeds such as Serrated tussock (Nassella trichotoma). Conversely, the modelled potential distribution of weeds is likely to be overestimated. This occurs as the broad scale (i.e. 1:250 000) of the statewide databases used, merges minor differences into the larger BVTs or land uses for each grid. Micro habitats within a vegetation or land use type maybe unsuitable for the particular weed species, and micro habitats outside the identified susceptible land use or vegetation type may be suitable but not recognised (eg. roadsides, small riparian or vegetation corridors). More detailed map layers, such as Ecological Vegetation Classes (EVCs), will produce better quality predictions.

The many weeds recorded as occurring along roadsides presents another major limitation when predicting potential distribution. Victoria has over 170 000 kilometres of roads, however to include all these roads within the image would not be suitable, as it would be too cluttered and meaningless. Thus, some potential distribution images may not include the occurrence of weeds within a region, if they only occur along roadsides. For example, Horehound (Marrubium vulgare) can occur along roadsides within cropping regions, but is unable to withstand cultivation. Similarly, some riparian weeds may occur along small rivers, streams and water channels, but are not included in the riparian or riverine vegetation classes of the BVT GIS layer, as they are too small or scattered to be detected, and so don’t appear on the predicted potential distribution maps.

The above limitations highlight the need for suitable actions to be undertaken.

Where information on a weeds present distribution is known but not recorded, records need to be updated to ensure management and monitoring are effectively undertaken. An accurate comparison of a weeds present distribution with its potential distribution allows managers to make decisions on the course of actions to take. The ratio of present and potential distribution provides an indication as to what stage the weed is at. Another way of expressing this is the relative position of the species on its invasion graph.

Invasion graph indicating stages of expansion of a new species into a habitat. (Adapted from Groves (1992) and Hobbs (1991)).

Weeds that have reached or nearly reached the full limits of their distribution, are not a major concern in terms of potential spread and impacts. Whereas, weeds currently occupying a small area of their potential range, or in the ‘lag or sleeper’ phase, should become a management priority. Indeed, a powerful weapon against weed invasions arising from existing infestations is early intervention. Early intervention not only achieves better in government/land manager investment, but also reduces costs of control and impact on the triple bottom line (social, environmental and agricultural values).

Regionally Controlled Weeds

Declared Noxious weeds that are widespread and established in a region (e.g. blackberry, ragwort). To prevent their spread, continuing control measures are required. Landholders have the responsibility to take all reasonable steps to control and prevent the spread of these weeds on their land and roadsides that adjoin their land. Landholders are responsible for controlling the growth and spread of these weeds on their land and the adjoining half width of the roadside (except where Vic Roads has responsibility for Declared Roads under the Transport Act 1983).

Regionally Prohibited Weeds

Declared Noxious weeds that are not widely distributed across Victoria, but are capable of spreading further (e.g. cape tulip). It is reasonable to expect that they can be eradicated from a region. Private landholders are responsible for control on private land but not on roadsides adjoining their property, which are the responsibility of Vic Roads, municipalities, or DEPI, depending on the class of road.

Restricted Weeds

Declared Noxious weeds that must not be sold or traded in Victoria. This category of Declared Noxious Weeds includes plants that are a serious threat to primary production, Crown Land, the environment or community health in another State (or Territory) of Australia - and that have the potential to spread into and within Victoria - posing an unacceptable threat

State Prohibited Weeds

These weeds either do not yet occur in Victoria but pose a significant threat if they invade, or are present, and do pose a serious threat and that it is reasonable to expect that they can be eradicated from Victoria. Control of these weeds is the responsibility of the Department of Environment and Primary Industries wherever they occur throughout Victoria.

Undeclared Weeds

These weeds are not classified under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994, but are recognised as a serious threat to agriculture and the environment.

References

ENRC (1998). Report on Weeds in Victoria. Environment and Natural Resources Committee. Parliament of Victoria.

Lane, D., Ritches, D. and Combellack, H. (1980). ‘A Survey of the Distribution of Noxious Weeds of Victoria’. Unpublished Report. Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Unpublished Report. Keith Turnbull Research Institute

McClaren, D. (1996). ‘Economics of Some Important Weeds/Insect pests to Victoria and Australia’. Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Unpublished Report. Keith Turnbull Research Institute.

Robinson, D., Davidson, I., and Tsaros, C. (1997). Conservation plan for the Grey-crowned Babbler in Victoria. Royal Australian Ornithologists Union and Department of Natural Resources and Environment.