Geraldton carnation weed (Euphorbia terracina)

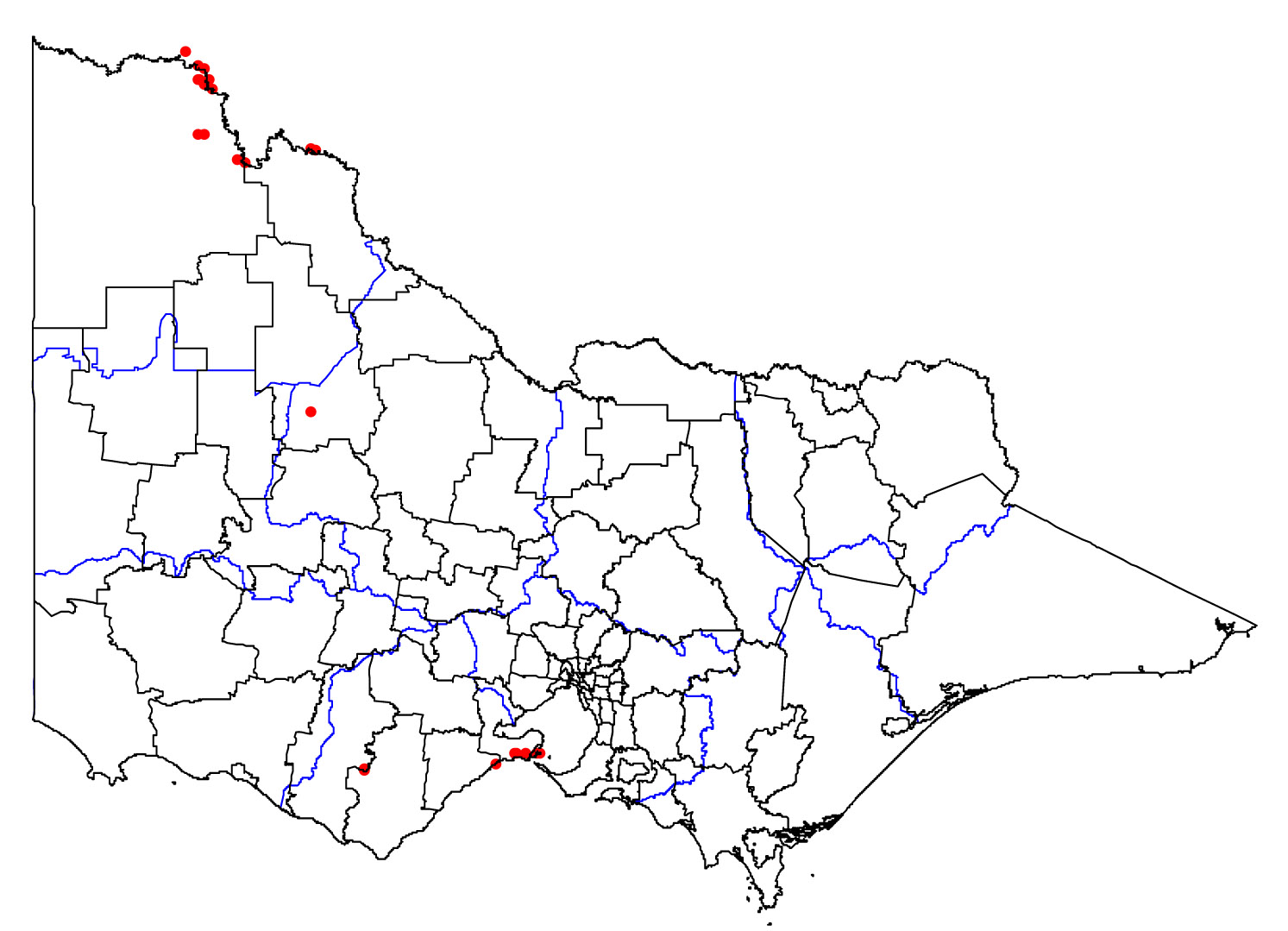

Present distribution

|  Map showing the present distribution of this weed. | ||||

| Habitat: Native to the Mediterranean region (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) “from the Canary Islands in the Atlantic, around the Mediterranean Sea coast and islands, on the north of the Red Sea coast and Black Sea to Georgia” (Keighery & Keighery, 2000). In its native range it occurs in waste places, on sandy flats and lower slopes (Reed, 1977); coastal areas and dunes (Keighery & Keighery, 2000). It is a weed of wasteland, paths and firebreaks (Keighery & Keighery, 2000); pasture, roadsides, coastal areas, bushland and disturbed sites in NSW, Vic, SA & WA (Richardson, 2006); coastal heath & tuart woodlands (Hussey et al, 1997); coastal dune and limestone heath, acacia shrubland, banksia woodland, ephemeral wetlands (Keighery & Keighery, 2000); closed tall scrub, low open & closed heath, closed Acacia shrub mallee (Town of Cambridge, 2006), and grows in well-drained sandy soils, particularly sand dunes (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) to 100ft (Meikle, 1985). Once thought to be weedy only in Australia (Keighery & Keighery, 2000), it has also been found in the USA in disturbed coastal sage scrub…open woodland-type vegetation and grassland (Calflora, 2006); swamps (WAH, 2006); saltmarsh, riparian areas and oak woodlands (DiTomaso, 2005). | |||||

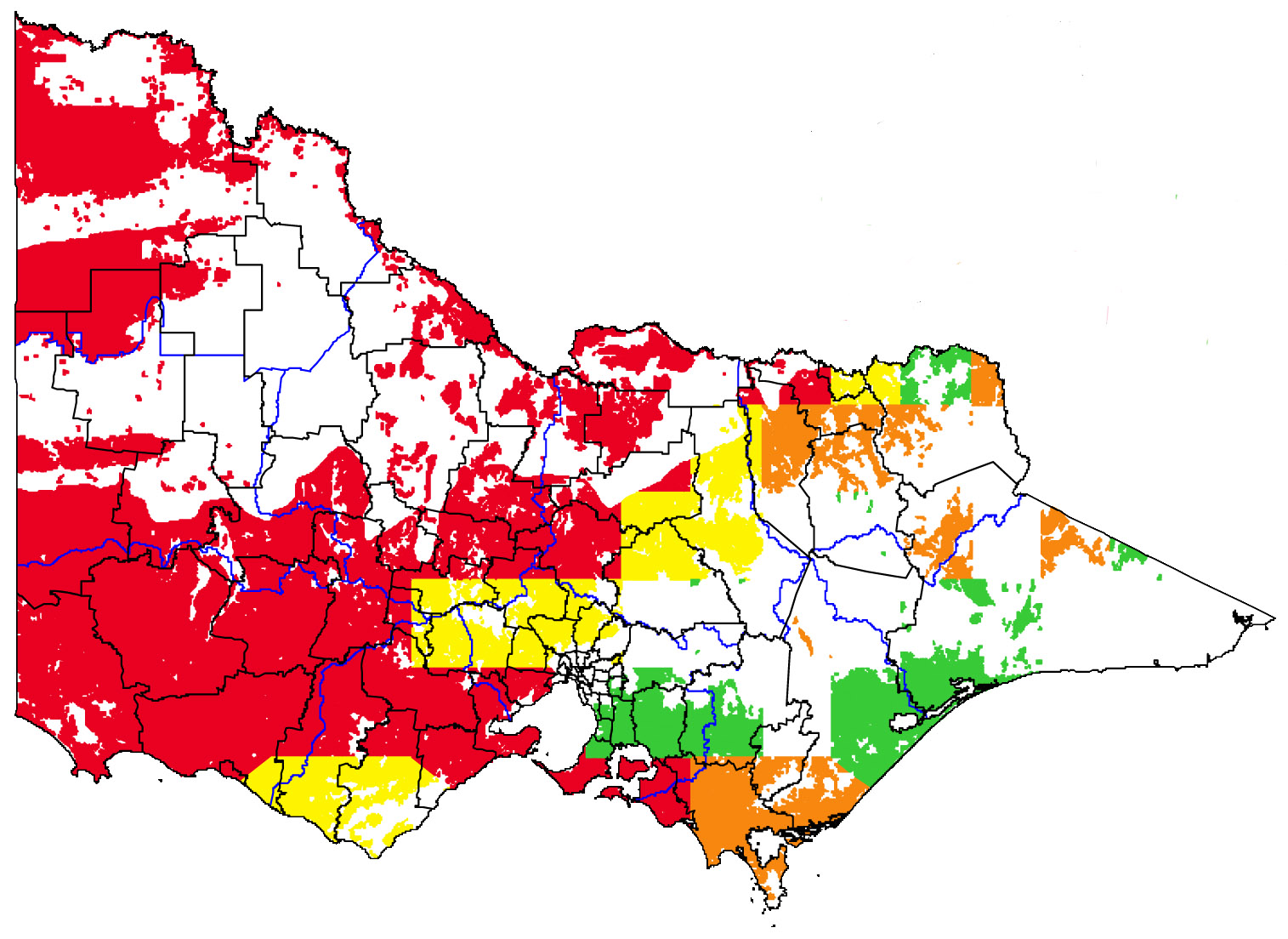

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Horticulture; pasture dryland; pasture irrigation Broad vegetation types Coastal scrubs and grassland; coastal grassy woodland; heathy woodland; heath; swamp scrub; inland slopes woodland; sedge rich woodland; grassland; plains grassy woodland; herb-rich woodland; riverine grassy woodland; riparian forest; rainshadow woodland; mallee; mallee heath; boinka-raak; mallee woodland; wimmera / mallee woodland Colours indicate possibility of Euphorbia terracina infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Can form dense monocultures (Brigham, 2005), but only grows to 1 m high (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) and has succulent stems (Keighery & Keighery, 2000). Not likely to impede individual access. | L | MH |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | “A very obvious weed…with a yellow hue that changes the look of the landscape” (Dempster, 2000). Minor effects to aesthetics | ML | MH |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Sap is highly caustic and can cause painful inflammations, temporary blindness, or permanent vision loss (Randall & Brooks, 2000). This plant can cause serious injuries to people throughout the year. | H | MH |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | This perennial herb (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) may have been introduced as an ornamental (Keighery & Keighery, 2000). It is not likely to have any structural effect and, as a possible ornamental plant, little effect on aesthetics either. | L | MH |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Whilst this species is known to invade ephemeral wetlands (Keighery & Keighery, 2000), swamps (Western Australian Herbarium, 2006), saltmarsh and riparian areas (DiTomaso, 2003), it is unlikely to affect the flow of waterways. | L | MH |

| 6. Impact water quality? | As a perennial herb, growing to about 1m high (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) this plant is unlikely to impact on water quality as it is not tall enough to shade waterways significantly. Its summer leaf loss is unlikely to fall into waterways in large enough concentrations to impact on water quality. | L | MH |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | This perennial herb (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) is unlikely to leave bare patches of soil open to erosion. | L | MH |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | Where this perennial herb (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) displaces grasses and herbs this plant is likely to cause an increase in biomass, however, “in summer most leaves are lost and many of the stems die back to the base,” (Keighery & Keighery, 2000), reducing the carbon stored by this plant. The result is probably a direct replacement of biomass. | ML | MH |

| 9. Change fire regime? | This plant is capable of displacing indigenous herbs and grasses (Town of Cambridge, 2006) and its succulent foliage that is summer-deciduous (Keighery & Keighery, 2000) may reduce the incidence and intensity of ground fires. As trees and shrubs persist, this effect would be moderate. | MH | M |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC= Semi Arid woodland (V); CMA=Mallee; Bioreg= Murray Mallee; CLIMATE potential=VH. Dense infestations in Australia of up to 85% canopy cover appear to seriously degrade herb/grass layer, but indigenous shrubs and trees persist (Town of Cambridge, 2006), however, in the US, this species can form monocultures that exclude all native vegetation (Brigham, 2005). Able to displace all herb/grass species. | H | MH |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC= Semi Arid woodland (D); CMA=Mallee; Bioreg= Lowan Mallee; CLIMATE potential=VH. Dense infestations in Australia of up to 85% canopy cover appear to seriously degrade herb/grass layer, but indigenous shrubs and trees persist (Town of Cambridge, 2006), however, in the US, this species can form monocultures that exclude all native vegetation (Brigham, 2005). Able to displace all herb/grass species. | H | MH |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC= Dunefield heathland (LC); CMA=Mallee; Bioreg=Lowan Mallee; CLIMATE potential=VH. Dense infestations in Australia of up to 85% canopy cover appear to seriously degrade herb/grass layer, but indigenous shrubs and trees persist (Town of Cambridge, 2006), however, in the US, this species can form monocultures that exclude all native vegetation (Brigham, 2005). Able to displace all herb/grass species. | H | MH |

| 11. Impact on structure? | “Forms dense thickets [to 1m high] which out compete native species for space, light and nutrients” (Randall & Brooks, 2000) and form dense monocultures that exclude all native vegetation in the US (Brigham, 2005). Dense infestations in Australia of up to 85% canopy cover appear to seriously degrade herb/grass layer, but indigenous shrubs and trees persist (Town of Cambridge, 2006). This species is capable of having a major impact on the herb/grass layer, but the monocultures of the US are unlikely to refer to trees and tall shrubs. | MH | MH |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | Threatens calcareous communities in southern Western Australia (Keighery & Keighery, 2000), however no specific information was found for Victorian flora. | MH | L |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | No information found. | MH | L |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | Dense thickets of E. terracina seriously degrading herbs and grasses (Randall & Brooks, 2000; Town of Cambridge, 2006) could reduce the food available to grazing fauna. | ML | M |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | This unpalatable weed (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) is “poisonous if eaten in large quantities” and “has no value as fodder” (Orchard & O’Neil, 1957). Whilst this information relates to stock, it is unlikely to provide benefit to indigenous fauna either. | H | MH |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | This unpalatable weed (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) is “poisonous if eaten in large quantities.” It may also be poisonous to indigenous fauna species when in leaf, however the “toxic sap deters native herbivores, like kangaroos” (Keighery & Keighery, 2000). May be poisonous if eaten. | MH | MH |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | This unpalatable weed (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) is “poisonous if eaten in large quantities” and “has no value as fodder” (Orchard & O’Neil, 1957). Whilst this information relates to stock, it is unlikely to provide benefit to pest fauna either. | L | MH |

| 18. Provides harbor? | “Provide little habitat value due to their toxic milky sap” (Brigham, 2005). | L | MH |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | Whilst Smith (2000) states that E. terracina “poses very little threat to agricultural land,” it is elsewhere described as a “common and serious weed of grazing lands” (Hussey et al, 1997). It “can be a serious competitor with pasture plants and is also toxic to stock,” contributing to stock losses. It is also unpalatable (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) and “has no value as fodder” (Orchard & O’Neil, 1957) so could have a major impact on stock yields. As it “does not persist on frequently cultivated soils” (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) it is not likely to be a weed of crops. | MH | MH |

| 20. Impact quality? | Whilst this plant may reduce quantity with stock losses, it is not likely to be a weed of crops (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001) and is not noted for causing loss of quality in livestock. | L | MH |

| 21. Affect land value? | There is no evidence that the presence of this plant affects land value. | L | L |

| 22. Change land use? | Control is possible with cultivation, but on light sandy soils, sowing to perennial pasture is a more soil-suitable solution (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001). Control options allow land use to continue unchanged. | L | MH |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | Older references only recorded successful control with heavily mown and grazed lucerne (O’Neil, 1959), which were considered to be “not economically practicable” (Clarke, 1939). Parsons & Cuthbertson (2001) suggest that simply sowing to perennial pasture as a solution. This may increase the cost of harvest slightly. | M | MH |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Not noted as a host for agricultural diseases. | L | M |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | Parsons & Cuthbertson (2001) state that “seeds germinate in late summer and autumn,” however, Dixon (2000) has observed germination occurring at any time of the year in damp land areas. Can germinate any time that water is available. | H | MH |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | Can adapt to, and does well in shade and high light (Brigham, 2004), however, no information was found about seedlings specifically. | M | L |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | “Entry into bushland seems to be via disturbance by grazing or fire, however, once established within a bushland anrea…can aggressively expand into natural bushland [and is able to] invade relatively undisturbed coastal heath” (Keighery & Keighery, 2000). Potential to invade healthy bushland (Randall & Brooks, 2000). Has invaded coast scrub areas “that do not appear to be disturbed” (DiTomaso, 2005). Establishes in relatively intact ecosystems. | MH | MH |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Shrub-like herb (Randall & Brooks, 2000). | L | MH |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | Whilst similar to leafy spurge, which does appear to have allelopathic properties (DiTomaso, 2005), no evidence was found for allelopathy in this species, however, there is not a lot of information about the biology of this plant. | M | L |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Grazing was used to aid control of seedlings in South Australia (O’Neil, 1959), however it is “unpalatable and stock do not usually eat older plants” (Orchard & O’Neil, 1957). The “toxic sap [also] deters native herbivores, like kangaroos” (Keighery & Keighery, 2000). Consumed but not preferred. | MH | MH |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Rapid (Randall & Brooks, 2000). | H | MH |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Likely killed by fire (Randall & Brooks, 2000). Observed “growing on sandy rises in low rainfall country” (O’Neil, 1959); toxic qualities increase during drought (Orchard & O’Neil, 1957); grows on sand dunes; from sea level to 100ft (Meikle, 1985). Found in ephemeral wetlands (Keighery & Keighery, 2000); swamps (WAH, 2006) and saltmarsh (DiTomaso, 2005). Likely to be highly tolerant of salinity, waterlogging and of drought. Not tolerant of fire. Tolerance of frost unknown. | MH | MH |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | Does not spread vegetatively, seeds only (Randall & Brooks, 2000); spread by seed (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001). “Outbreeding but capable of self-pollination” (Keighery & Keighery, 2000). Sexual reproduction- self and cross fertile. | ML | MH |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | Prolific (Randall & Brooks, 2000). No further information found. | M | L |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | 3-5 years (Randall & Brooks, 2000). | L | MH |

| 12. Reproductive period? | Short-lived (D Keighery & Keighery, 2000) biennial or perennial (Reed, 1977) that forms dense monocultures (Brigham, 2005). | H | MH |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | Seedlings emerge in winter and flower in spring (Randall & Brooks, 2000); seeds germinate in late summer and autumn, grow during winter, and commence flowering in spring (Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001), producing seed in less than one year. | H | MH |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Explosive fruit burst distributes seed several metres, water and animals can also transport seed (Randall & Brooks, 2000; Parsons & Cuthbertson, 2001). Possibly dispersed by birds in Australia (Keighery & Keighery, 2000). Feral doves have been observed eating the seed (Betts, 2000), however, a wild dove study recovered 1 non-viable (Euphorbia esula) seed from faeces and in a feeding trial, seed viability was reduced to 2-25% (from a normal viability of 89-97%) (Wald et al, 2005). | MH | MH |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | Most propagules are distributed several metres (Randall & Brooks, 2000), however this species is found in riparian areas (DiTomaso, 2005), so transport in water might take some seed several kilometers. | ML | MH |

References

Betts, B. 2000, ‘The control of Geraldton carnation Weed (Euphorbia terracina) in the City of Stirling ,’ Euphorbia terracina (Geraldton Carnation Weed or Spurge) A Guide to its Biology and control and Associated Safety Issues, Proceedings of a Workshop conducted by Environmental Weeds Action Network (Inc.), Perth, p. 18.

Brigham, C. 2005, ‘High School Students Take On Carnation Spurge,’ Cal-IPC News, vol. 13(2), p.6. www.cal-ipc.org/resources/news/pdf/cal-ipc_news7302.pdf

Clarke, G.H. 1939, ‘Important Weeds of South Australia II,’ Bulletin of the Department Agriculture South Australia, vol. 343(52), p. 9-13.

Dempster, H. 2000, ‘Introduction,’ Euphorbia terracina (Geraldton Carnation Weed or Spurge) A Guide to its Biology and control and Associated Safety Issues, Proceedings of a Workshop conducted by Environmental Weeds Action Network (Inc.), Perth, p. 3.

DiTomaso, J. 2003, ‘Part IV. Plant assessment Form,’ California Invasive Plant Council, viewed: http://portal.cal-ipc.org/files/PAFs/Euphorbia%20terracina.pdf

Dixon, B. 2000, ‘Distribution of Geraldton carnation Weed (Euphorbia terracina) in Kings Park Bushland,’ Euphorbia terracina (Geraldton Carnation Weed or Spurge) A Guide to its Biology and control and Associated Safety Issues, Proceedings of a Workshop conducted by Environmental Weeds Action Network (Inc.), Perth, p. 3.

Hussey, B.M.J. Keighery, G.J. Cousens, R. D. Dodd, J. & Lloyd, S. 1997, Western Weeds, Plant Protection Society of WA, Victoria Park, WA.

Keighery, B. & Keighery, G. 2000, ‘Biology and Weed Risk of Euphorbia terracina in Western Australia,’ Euphorbia terracina (Geraldton Carnation Weed or Spurge) A Guide to its Biology and control and Associated Safety Issues, Proceedings of a Workshop conducted by Environmental Weeds Action Network (Inc.), Perth, p. 4-7.

Meikle, R.D. 1985, Flora of Cyprus, volume 2, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

O’Neil, J.M. 1959, ‘Lucerne eradicates false caper,’ Journal of the Department of Agriculture South Australia, vol. 62(12), p. 541-2.

Orchard, H.E. & O’Neil, J.M. 1957, ‘Weeds of South Australia. False Caper (Euphorbia terracina, L.),’ Journal of the South Australian Department of Agriculture, p. 237-244.

Parsons W.T. & Cuthbertson E.G. 2001, Noxious weeds of Australia, 2nd ed., CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood

Randall, R. & Brooks, K 2000, Managing Weeds In Bushland- Geraldton Carnation Weed, Environmental Weeds Action Network (EWAN), West Perth,

Reed, C.F. 1977, Economically Important Foreign weeds, United States Department of Agriculture.

Smith, E. 2000, ‘Anecdote #1,’ Euphorbia terracina (Geraldton Carnation Weed or Spurge) A Guide to its Biology and control and Associated Safety Issues, Proceedings of a Workshop conducted by Environmental Weeds Action Network (Inc.), Perth, p. 3.

Town of Cambridge 2004, Natural Remnant Bushland Areas Draft Conservation Strategy, Town of Cambridge, Perth, WA,

www.cambridge.wa.gov.au/information/your_env/docs/apnas/file/at_download

Wald, E.J. Kronberg, S.L. Larson, G.E. & Johnson, W.C. 2005 ‘Dispersal of leafy spurge (Euphorbia esula L.) seeds in the feces of wildlife,’American Midland Naturalist, vol. 154(2), pp.342-357.

Western Australian Herbarium (1998–). Euphorbia terracina, FloraBase — The Western Australian Flora. Department of Environment and Conservation. Viewed: 1/2/2006, http://florabase.calm.wa.gov.au/

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) 2006, Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, viewed 26/9/2006, http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/

Beckett, E. 1988, wild Flowers of Majorca, Minorca and Ibiza, AA Balkema, Rotterdam and Brookfield.

Calflora: Information on California plants for education, research and conservation. [web application]. 2006. Berkeley, California: The Calflora Database [a non-profit organization]. Available: http://www.calflora.org/. [Accessed: 26/09/2006.]

Davis, P.H. 1982, Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands, volume 7, University Press, Edinburgh.

DiTomaso, J.M. 2005, Plant Assessment Form, California Invasive Plant Council, viewed: 02/01/2007, http://portal.cal-ipc.org/files/PAFs/Euphorbia%20terracina.pdf

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2006, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed 26/11/2006, http://www.gbif.org/

Hansen, A. & Sunding, P. 1985, Flora of Macaronesia, Sommerfeltia; no.1, Botanical Garden and Museum, Oslo.

Hussey, B.M.J. Keighery, G.J Cousens, R.D. Dodd, J. & Lloyd, S. 1997, Western Weeds, Plant Protection Society of WA, Victoria Park, WA.

Keighery, B. & Keighery, G. 2000, ‘Biology and Weed Risk of Euphorbia terracina in Western Australia,’ Euphorbia terracina (Geraldton Carnation Weed or Spurge) A Guide to its Biology and control and Associated Safety Issues, Proceedings of a Workshop conducted by Environmental Weeds Action Network (Inc.), Perth, p. 4-7.

Meikle, R.D. 1985, Flora of Cyprus, The Bentham-Moxon Trust, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) 2006, w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, viewed: 26/11/2006, http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html

Parsons, W.T. & Cuthbertson, E.G. 2001, Noxious weeds of Australia, 2nd ed., CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood.

Reed, C.F. 1977, Economically Important Foreign weeds, United States Department of Agriculture.

Richardson, F.J. 2006, Weeds of the south-east: an identification guided for Australia, R.G and F.J. Richardson, Meredith, Victoria.

Royal Botanic Gardens (RBG) 2006, Flora Zambesiaca, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK, viewed 13/12/2006, https://www.kew.org/science/projects/flora-zambesiaca-fz

Town of Cambridge 2006, Natural Remnant Bushland Areas Draft Conservation Strategy, Town of Cambridge, Perth, WA,

www.cambridge.wa.gov.au/information/your_env/docs/apnas/file/at_download

Western Australian Herbarium (WAH) 2006, Euphorbia terracina, FloraBase — The Western Australian Flora. Department of Environment and Conservation. http://florabase.calm.wa.gov.au/

Willkomm, M. 1893, Supplementum prodromi florae hispanicae, Schweizerbart, Stuttgartiae.

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.