Saltcedar (Tamarix ramosissima)

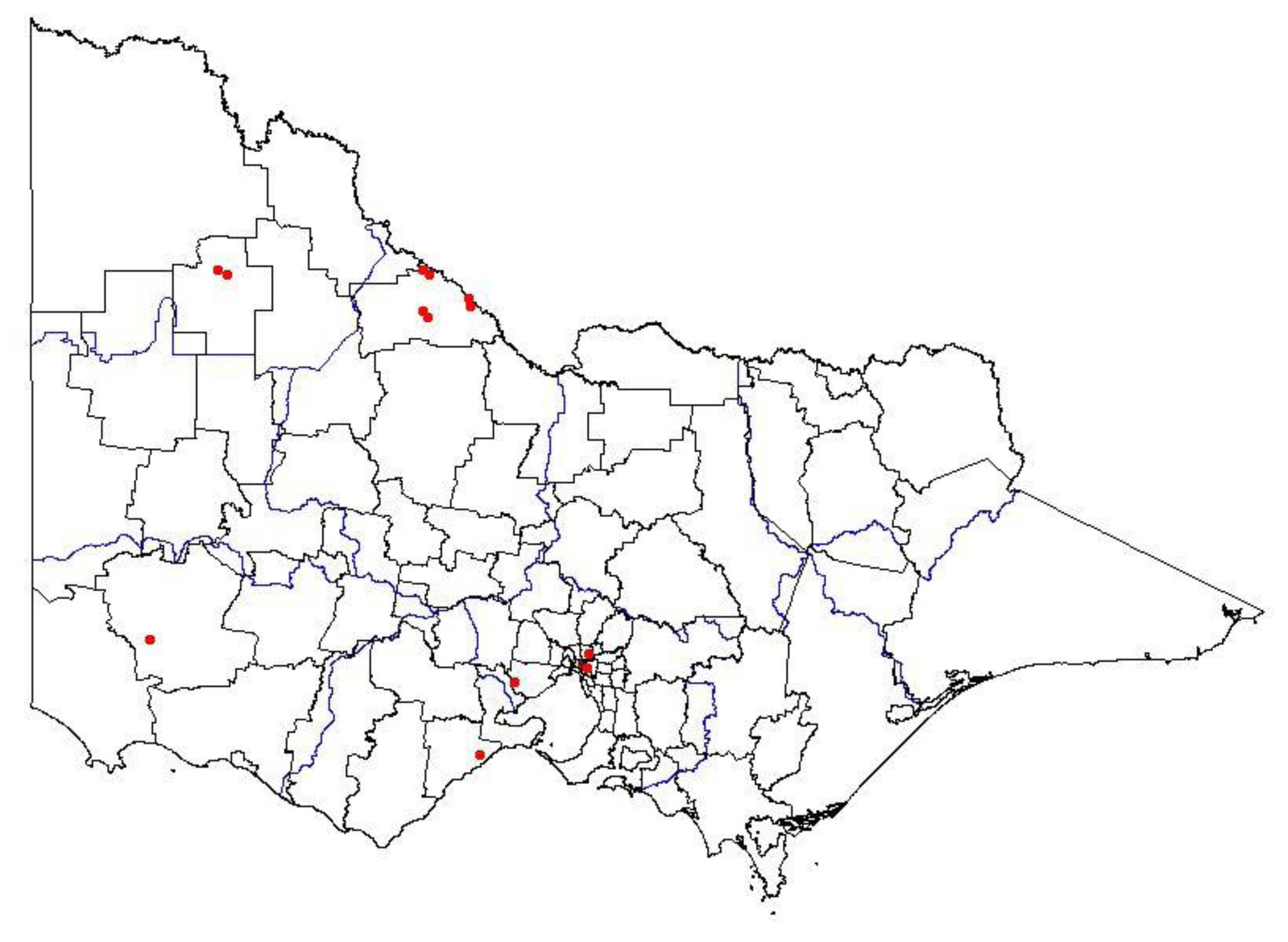

Present distribution

|  Map showing the present distribution of this weed. | ||||

| Habitat: Native to Ukraine, former USSR, Korea, China, Mongolia, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan & Pakistan (Baum, 1978; Jafri & El-Gadi, 1979). Reported in flood plains, grazing land/salt grass pasture, reservoirs, streams, canals, lake shores, outlying ephemeral watercourses, isolated marshes and springs, and has invaded nearly every drainage system in arid and semi-arid USA (Stevenson, 1996; De Gouvenain, 1996; Whitson, 1992; Zouhar, 2003; Baum, 1978). | |||||

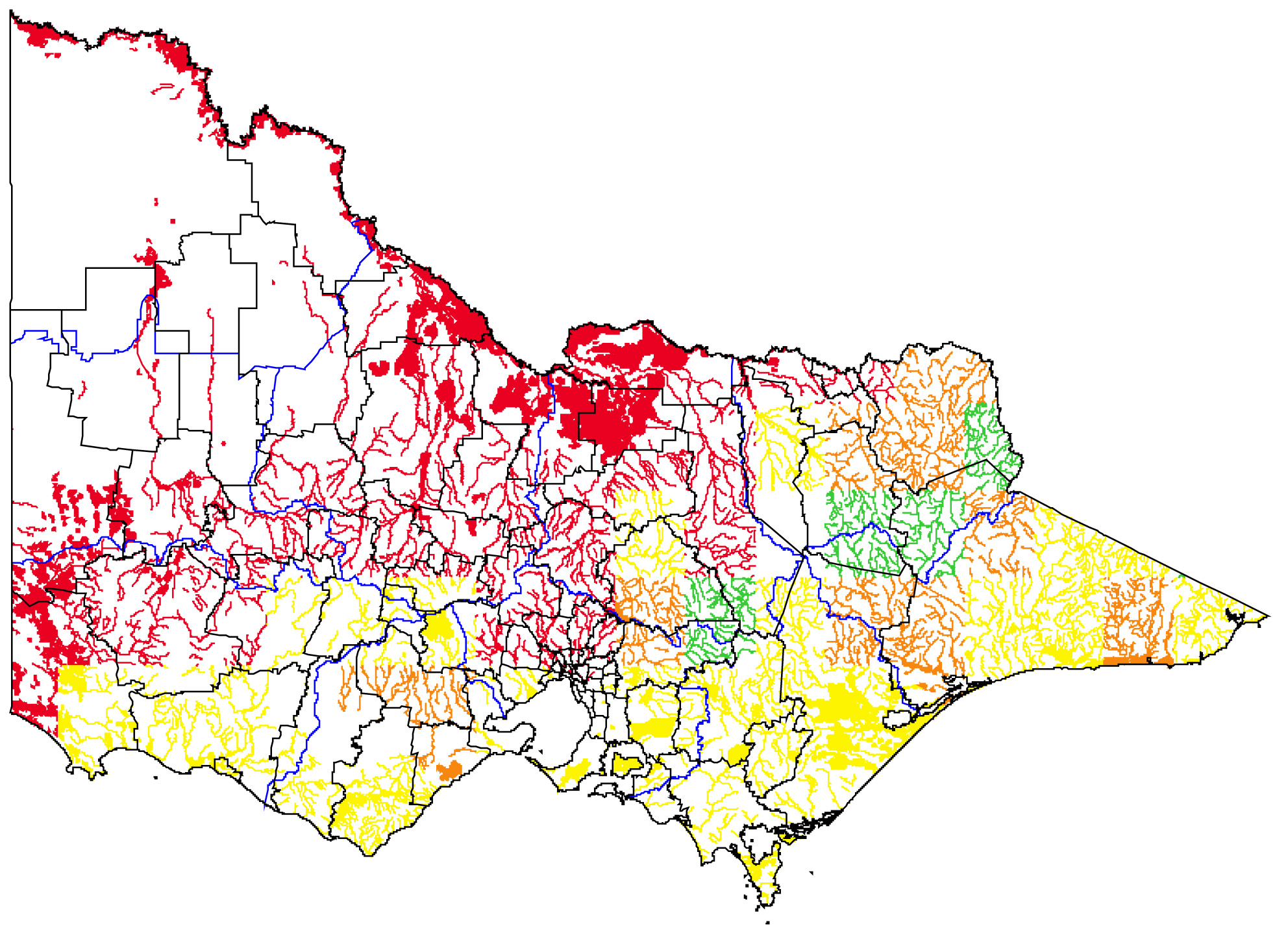

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Horticulture; pasture irrigation Broad vegetation types Coastal scrubs and grassland; coastal grassy woodland; heathy woodland; swamp scrub; sedge rich woodland; riverine grassy woodland; riparian forest. and a riparian buffer zone of 10m for rivers and 5m for creeks. Colours indicate possibility of Tamarix ramosissima infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | In some areas, “tamarisk often occurs in dense, monotypic” (Zouhar, 2003) impenetrable thickets (DeLoach, 2006). In the US it “substantially reduces recreational usage of parks…and other riparian areas…because saltcedar creates nearly impenetrable stands that block access to other habitats” (Dudley et al, 2000). Major impediment to access. | H | MH |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | “Saltcedar substantially reduces recreational usage of parks, national wildlife refuges, and other riparian areas for camping, hunting and fishing, boating, bird watching and wildlife photography” in the USA (Dudley et al, 2000). This major impact on recreational activities may lead to reduced visitor numbers. | H | MH |

| 3. Injurious to people? | No evidence for injury in the extensive impact literature for this species. | L | MH |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | No evidence found that root systems cause structural damage. The root system tends to grow “downward with little branching until it reaches the water table, [when] root branching becomes profuse” (DiTomaso, 1996). Dense stands (Zouhar, 2003) of shrubby trees to 6m (Baum, 1978) could have a moderate visual effect. | MH | MH |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Capable of high rates of evapotranspiration, capable of lowering the underground water table (Zouhar, 2003). Traps and stabilizes alluvial sediments, reducing the width, depth, and water-holding capacity of river channels and increasing the frequency and severity of overbank flooding (Zouhar, 2003). The total water flow along drainages with heavy infestations of saltcedar can be reduced or even eliminated (Grubb et al, 2006). Major effects on surface and subsurface water flow. | H | MH |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Causes changes in turbidity and water temperature in the US (Dudley et al, 2000). Effect on light levels, but no evidence of increased algal growth. | ML | MH |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | Coastal reclamation of sands and mudflats (Webb et al, 1988), introduced to US to prevent soil erosion (DeLoach et al, 1996); established in China to control mobile sand dunes and wind erosion (Hui et al, 1996), however, in riparian environments, it increases the frequency and severity of overbank flooding (Zouhar, 2003), which could lead to large scale soil movement. | ML | MH |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | Can establish in bare sections of river or creekbeds (Dudley et al, 2000) or ephemeral rivers (Zouhar, 2003); can reach densities of 62 basal branches /m2 (Pauca et al, 1996). Likely to increase biomass under these circumstances. | L | MH |

| 9. Change fire regime? | Saltcedar leaves are not highly flammable due to high moisture content, even though they contain volatile oils. However, “saltcedar flammability increases with the build-up of dead and senescent woody material within the plant,” and dense stands of tamarisk can be highly flammable. Fire appears to be less common in riparian ecosystems where tamarisk has not invaded. Increases in fire size and frequency are attributed to a number of factors including an increase in ignition sources, increased fire frequency in surrounding uplands, and increased abundance of fuels. (Zouhar, 2003). Tamarisk also promotes increased fire frequencies in plant communities that are generally fire-intolerant (Lovich, 1996), such as riparian vegetation. This constitutes a major change to fire intensity and frequency. | H | MH |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC=Riverine Grassy Woodland (V); CMA=North Central; Bioreg=Murray Fans; CLIMATE potential=VH. Considered the worst weed of southwestern riparian areas (DeLoach et al, 1996). In some areas, “occurs in dense, monotypic stands…Once a dense stand of tamarisk is established, there tends to be little regeneration of other species” (Zouhar, 2003). Can form monotypic stands causing major displacement of dominant species. | MH | MH |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC=Coastal Headland Scrub (D); CMA=Corangamite; Bioreg=Otway Ranges; CLIMATE potential=H. Considered the worst weed of southwestern riparian areas (DeLoach et al, 1996). In some areas, “occurs in dense, monotypic stands…Once a dense stand of tamarisk is established, there tends to be little regeneration of other species” (Zouhar, 2003). Can form monotypic stands causing major displacement of dominant species. | MH | MH |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC=Heathy Woodland (LC); CMA=Glenelg-Hopkins; Bioreg=Glenelg Plain; CLIMATE potential=VH. Considered the worst weed of southwestern riparian areas (DeLoach et al, 1996). In some areas, “occurs in dense, monotypic stands…Once a dense stand of tamarisk is established, there tends to be little regeneration of other species” (Zouhar, 2003). Can form monotypic stands causing major displacement of dominant species. | MH | MH |

| 11. Impact on structure? | “Has almost completely replaced the native forest that historically dominated the riparian corridor” on the Colorado River. In some areas, “occurs in dense, monotypic stands…Once a dense stand of tamarisk is established, there tends to be little regeneration of other species” (Zouhar, 2003). In Australia, where tamarisk is not native, it is capable of replacing native plant communities with an assemblage comprised of only a few species of introduced and salt tolerant plants (Lovich, 1996). Can form monotypic stands and can have a serious impact on all vegetation layers. | H | MH |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | The ability to form monocultures or replace native plant communities with a few introduced species (see Q. 11) has the potential to have a major impact on threatened flora species, however none are documented. | MH | L |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | The ability to form monocultures or replace native plant communities with a few introduced species (see Q. 11) has the potential to have a major impact on the habitat and food sources for threatened fauna species, however, none have been documented. | MH | L |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | “Lacks palatable fruits and seed, fails to harbour plant-eating insects that insectivores can eat, occurs in high-density stands with little structural or microclimatic diversity, and is too small in stature and limb size to meet the habitat requirements of raptors and woodpeckers (Zavaleta, 2000). The ability to form monocultures or replace native plant communities with a few introduced species (see Q. 11) has the potential to have a major impact on the habitat and food sources for fauna species, reducing numbers of individuals, but probably not to local extinction. | MH | L |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | "Although saltcedar provides habitat and nest sites for some wildlife (e.g. white-winged dove), most authors have concluded that it has little value to most native amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals" (Zouhar, 2003). May provide habitat/ nesting sites for some indigenous fauna. | MH | MH |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | No evidence for injury in the extensive impact literature for this species. | L | MH |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | Along the shoreline of Lake Powell, black-tailed jackrabbits use saltcedar as a major food source (Zouhar, 2003). May provide food for a serious pest in Australia. | MH | MH |

| 18. Provides harbor? | "Although saltcedar provides habitat and nest sites for some wildlife (e.g. white-winged dove), most authors have concluded that it has little value to most native amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals" (Zouhar, 2003). May provide habitat for some exotic bird species. | ML | MH |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | “Tamarisk has ruined once valuable grazing lands. On the Walker River Indian Reservation, where many residents depend on cattle grazing, several thousand acres of saltgrass pasture were lost to saltcedar” (Stevenson, 1996). However, “heavily salinised land is almost worthless in commercial farming terms,” (Hamblin, 2001) so the statewide impact is likely to be minor. | ML | MH |

| 20. Impact quality? | Unlikely to contaminate produce, as there is no evidence that the plant damages stock and a tree is unlikely to contaminate a crop. | L | MH |

| 21. Affect land value? | See Q 19. Statewide, this weed would have little affect on land value. | L | MH |

| 22. Change land use? | See Q. 19. This weed is unlikely to change landuse significantly across a statewide scale. | L | MH |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | Capable of high rates of evapotranspiration, capable of lowering the underground water table (Zouhar, 2003). “Nearly impenetrable stand[s] that block access” (Dudley et al, 2000) to waterways for stock. Providing alternative water sources for irrigation and stock supplies may increase harvest costs slightly. | MH | MH |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Not recorded as such in the extensive literature on this plant. | L | MH |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | No dormancy requirements, germinate in less than 24 hrs, require moist, fine-grained soil (Stevens, 2002). Germinate any time when water is available. | H | MH |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | Tamarisk decline under shade (Zouhar, 2003). Requires open space. | ML | MH |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Frequently associated with disturbance, but able to invade relatively undisturbed riparian areas (Zouhar, 2003). Establishes in natural ecosystems that are usually subject to minor disturbance. | MH | MH |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | “Underground lateral roots are actually rhizomes” and mature plants can reproduce from adventitious roots following removal of topgrowth (Zouhar, 2003). Geophyte. | ML | MH |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | Salt accumulates in leaves and is transferred to the soil surface with leaf drop, which can impair germination and establishment of native flora (Zouhar, 2003). Allelopathic properties seriously affect some plants. | MH | MH |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Several potential biocontrol insects can cause noticeable damage and even tree death, but these species do not appear to be present in Australia (DeLoach et al, 1996). May be grazed but are not preferred (to cottonwood and willow seedlings) (Zouhar, 2003). Able to resprout vigorously following canopy removal (by fire) (Zouhar, 2003). Consumed but not preferred; capable of rapid recovery. | MH | MH |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Very rapid (3-4m per year) (Zouhar, 2003). | H | MH |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Greater drought and flood tolerance than the native S. exigua in USA. Observed tolerating more than two years of root-crown inundation (Stevens, 2002). Tolerates elevated soil salt levels. Sprouts from root crown following fire. This resprout ability also allows it to tolerate freezing conditions and grazing (Zouhar, 2003). Highly tolerant of waterlogging, salinity, and tolerant of fire, frost and drought. | H | MH |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | “Most wild plants have probably originated from detached shoots, because only in a small area of the lower Rakaia R[iver] bed are fruiting plants and seedlings known” (Webb et al, 1988). Seed (Zouhar, 2003). Sexual and vegetative reproduction. | H | MH |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | Mature plants can produce 250 000 000 seeds per year (Stevens, 2002). | H | MH |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | Seeds short-lived (less than 2 months in Summer) (Stevens, 2002). If seeds are not germinated during the summer that they are dispersed, almost none germinate the following spring (Zouhar, 2003). | L | MH |

| 12. Reproductive period? | “Shrubs 75 to 100 years old have not yet shown signs of deteriorating due to age” (Zouhar, 2003). | H | MH |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | May flower in their first year of growth (Zouhar, 2003) | H | MH |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Wind blown (by small hairs on seed coat) and water-dispersed seed (Zouhar, 2003). | MH | MH |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | A US study found populations concentrated around towns, but that one population had probably spread downstream in floods, a distance of at least 160km (from Melstone to Fort Peck reservoir, Montana) (Pearce & Smith, 2003). Given its ability to invade riparian habitats (Zouhar, 2003), some propagules could easily spread more than 1km. | H | MH |

References

Baum, B.R. 1978, The Genus Tamarix, The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Jerusalem.

De Gouvenain, R.C. 1996, ‘Origin, History and Current Range of Saltcedar in the U.S.,’ In DiTomaso, J.M. & Bell, C.E. (eds.) Proceedings The Saltcedar Management Workshop, June 12, 1996, http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/docs/news/workshopJun96/Paper1.html

DeLoach, C.J. 1996, ‘Saltcedar Biological Control: Methodology, Exploration, Laboratory Trials, Proposals for Field Releases, and Expected Environmental Effects,’ In Proceedings Saltcedar Management and Riparian Restoration Workshop Las Vegas, Nevada September 17 and 18, 1996, http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/docs/news/workshopSep96/deloach.html

DeLoach, C.J. Pitcairn, M.J. & Woods, D. 1996, ‘Biological Control of Saltcedar in Southern California,’ In DiTomaso, J.M. & Bell, C.E. (eds.) Proceedings The Saltcedar Management Workshop, June 12, 1996, http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/docs/news/workshopJun96/Paper9.html

DiTomaso, J.M. 1996, ‘Identification, Biology and Ecology of Saltcedar,’ In DiTomaso, J.M. & Bell, C.E. (eds.) Proceedings The Saltcedar Management Workshop June 12, 1996, http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/docs/news/workshopJun96/Paper2.html

Dudley, T.L. DeLoach, C.J. Lovich, J.E. & Carruthers, R.I. 2000, ‘Saltcedar Invasion of Western Riparian Areas: Impacts and New Prospects for Control,’ In

(McCabe, R.E & Loos, S.E. (eds.) Transaction of the Sixty-fifth North American Wildlife and Natural Resource Conference, Wildlife Management Institute, Washinton D.C.

Grubb, R.T Sheley, R.L & Calstrom, R.D. 2006, Saltcedar (Tamarisk), Montana State University Extension MontGuide MT 199710, www.montana.edu/wwwpb/pubs/mt9710.pdf

Hamblin, A. 2001 Land Theme Report Australia State of the Environment Report, CSIRO Publishing on behalf of the Department of the Environment and Heritage, Canberra, http://www.deh.gov.au/soe/2001/land/land04-2.html#l3-3a

Hui, Y. Chen, C. Zhao, S. Zhang, C. Hui, Y.J. Chen, C. Zhao, S.Z. & Zhang, C.Y. 1996, ‘Technigues for controlling grassland desertification by cultivating grass and shrubs,’ Grassland of China, vol. 4, p. 19-23.

Lovich, J.E. 1996, ‘A Brief Review of theImpacts of Tamarsk, or Saltcedar on Biodiversity in the New World,’ In In Proceedings Saltcedar Management and Riparian Restoration Workshop Las Vegas, Nevada September 17 and 18, 1996, http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/docs/news/workshopSep96/lovich.html

Pauca, C.M. Vasiliu, O.L. Vasu, A. Bazac, G. Arion, c. Serbanescu, G.H. Tacina, A. Falca, M. Honciuc, V. Tatole, V. Sterghiu, C. & Ceianu, I. 1996, ‘Ecosystemic characterization of a Tamarix ramosissima shrubland in the Danube Delta (Sulina),’ Revue Roumaine de Biologie. Serie de Biologie Vegetale, vol. 41(2), p. 101-111.

Pearce, C.M. & Smith, D.G. 2003, ‘Saltcedar: Distribution, abundance, and dispersal mechanisms, Northen Montna, USA,’ Wetlands, vol. 23(2), p. 215-228.

Stevens, L.E. 2002, Exotic Tamarisk on the Colorado Plateau, CP-LUHNA, USA, http://www.cpluhna.nau.edu/Biota/tamarisk.htm

Stevenson, T. 1996, ‘Nevada’s Perspective of Habitat Loss Due to Saltcedar Invasion,’ In Proceedings Saltcedar Management and Riparian Restoration

Workshop Las Vegas, Nevada September 17 and 18, 1996, http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/docs/news/workshopSep96/stevenson.html

Webb, C.J., Sykes, W.R., Garnock-Jones, P.J., 1988, Flora of New Zealand, Vol 4, Botany Division, Department of Scientific & Industrial Research, New Zealand.

Whitson, T.D. (ed.) 1992, Weeds of the West, Revised Edition, Western Society of Weed Science in cooperation with the Western United States Land Grant Universities Cooperative Extension Services, California.

Zavaleta E. 2000, ‘Valuing Ecosystem Services Lost to Tamarix Invasion in the United States,’ in Mooney, HA. & Hobbs, R.J. Invasive Species in a Changing World, Island Press, USA.

Zouhar, K. 2003, Tamarix spp. Fire Effects Information System, U.S. Department of Agricutlure, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, viewed: 24/10/2006, http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) 2006, Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, viewed: 22/11/2006, http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/

Calflora: Information on California plants for education, research and conservation. [web application], Berkeley, California: The Calflora Database [a non-profit organization] viewed: 22/11/2006, http://www.calflora.org/.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2006, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed 22/11/2006, http://www.gbif.org/

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) 2006, w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, viewed: 22/11/2006, http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.