Mistflower (Ageratina riparia)

Present distribution

|  This weed is not known to be naturalised in Victoria | ||||

| Habitat: Native to Central America. In New Zealand, a weed of forest margins, open spaces, poorly managed pasture, wetlands and streambanks (Barton et al 2006). In Hawaii, occurs in dry disturbed habitats to mesic and wet forest (PIER). Found in subtropical and tropical rainforests (Parsons & Cuthbertson 1992), along shaded riverbanks, steep, south-facing hillsides, and other sheltered moist places. In Australia a major weed in the mountainous, high-rainfall districts of south-eastern Queensland and north-eastern New South Wales (Wilson & Graham 2000). | |||||

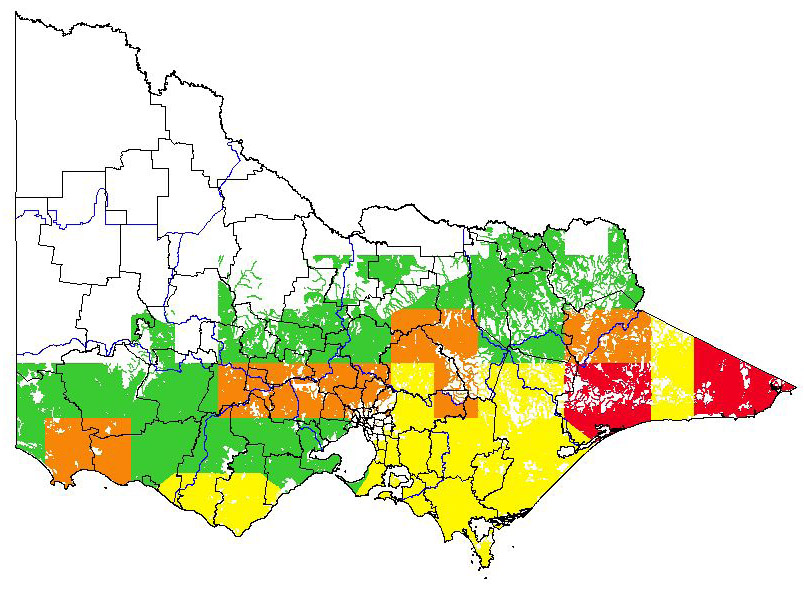

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Forest private plantation; forest public plantation; horticulture; pasture dryland; pasture irrigation Broad vegetation types Coastal grassy woodland; lowland forest; swamp scrub; sedge rich woodland; moist foothills forest; montane moist forest; sub-alpine woodland; grassland; valley grassy forest; sub-alpine grassy woodland; montane grassy woodland; riverine grassy woodland; riparian forest Colours indicate possibility of Ageratina riparia infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Restricts movement of machinery (Wilson & Graham 2000). High nuisance value. People and vehicles access with difficulty. | MH | MH |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | ‘It is common beside walking tracks and along river systems in native forests’ (Barton et al 2006). Likely to impede river access due to dense infestations in riparian zones. Some recreational uses affected. | MH | H |

| 3. Injurious to people? | There is no evidence in the literature to suggest it has properties that are injurious to people. | L | MH |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | There is no information documented to suggest it causes structural damage to cultural sites. ‘…can become a dominant understorey plant’ (Wilson & Graham 2000). A moderate visual affect is possible due to the nature of the plant to dominate the understorey. | ML | MH |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Common in riparian areas but due to its vegetative lifeform, eg. ‘Herb to subshrub’ (NZ PCN), it is likely to have little impact on water flow. | L | MH |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Terrestrial species. No likely to impact on water quality. | L | H |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | Colonies increase in size and density by layering, forming a mat of interwoven stems (Parsons & Cuthbertson 1992). Forms dense thickets (PIER). ‘…plants intertwine producing a blanket affect, giving effectively 100% groundcover’ (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000) ‘… covering whole mountainsides.’ (Parsons & Cuthbertson 1992). Not likely to increase soil erosion due to its matting habit and ability to form dense colonies. | L | MH |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | ‘Native plant species less than 1m in height may be smothered by A. riparia and the seedlings of taller plant species are deprived of light’ (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000). ‘…it can form large, dense mats of semi-woody stems which smother native plants and prevent their regeneration’ (Barton et al 2006). Its dense matting habit may in the short term increase biomass, but its ability to eliminate recruitment of larger woody species would likely decrease biomass in the longer term. Biomass slightly decreased. | MH | M |

| 9. Change fire regime? | Populations appear to increase following fire (Yadav & Tripathi 1982) but it is not known if this species alters the fire regime. | M | L |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC= Warm temperate rainforest (BCS= E); CMA= East Gippsland; Bioreg= Gippsland Plain; CLIMATE potential=VH. Dense mats of semi-woody stems smother native plants and prevents their regeneration (Barton et al 2006). Major displacement of some dominant spp. within the lower & middle strata. | MH | MH |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC= Riparian shrubland (BCS= R); CMA= East Gippsland; Bioreg= East Gippsland Uplands; CLIMATE potential=VH. Dense mats of semi-woody stems smother native plants and prevent their regeneration (Barton et al 2006). Major displacement of some dominant spp. within the lower & middle strata. | MH | MH |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC= Riparian Forest (BCS= LC); CMA= East Gippsland; Bioreg= East Gippsland Uplands; CLIMATE potential=VH. Dense mats of semi-woody stems smother native plants and prevent their regeneration (Barton et al 2006). Major displacement of some dominant spp. within the lower & middle strata. | MH | MH |

| 11. Impact on structure? | Smothers native plant species less than 1m in height, and the seedlings of taller plant species are deprived of light (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000). Dominates riverine groundcover habitats, excluding many native species (NRW QLD). Can become a dominant understorey plant (Wilson & Graham 2000). Dense mats of semi-woody stems smother native plants and prevents their regeneration (Barton et al 2006). Major effect on lower stratum and some effect on middle and top strata by smothering woody seedlings & reducing recruitment. | MH | H |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | In New Zealand mistflower is one of the main threats to the survival of the nationally vulnerable species, H. bishopiana, and has almost eliminated the nationally endangered species, H. acutiflora from Kerikeri falls, and started invading it’s only other known location. (Barton et al 2006). Evidence that mistflower can significantly reduce populations of threatened flora species in New Zealand. Potential for similar impacts in Victoria. | MH | MH |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | Dominate riverine groundcover habitats, excluding many native species and the native animals which are reliant on those plants (NRW QLD). A decrease in habitat quality for ground dwelling native animals, leading to a reduction in population numbers. Its impact specifically on threatened fauna species is not documented. | MH | ML |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | ‘…dominate riverine groundcover habitats, excluding many native species and the native animals which were reliant on those plants’ (NRW QLD). A decrease in habitat quality for ground dwelling native animals, leading to a reduction in population numbers. | MH | MH |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | ‘The red-necked pademelon, Thylogale thetis, browsed extensively on A. riparia’ (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000). Some evidence it provides a food source to desirable species. | MH | H |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | Toxic secondary metabolites have been identified in aerial parts of A. riparia (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000). Caused lung lesions in horses (Gibson & O’Sullivan 1984). Sheep and horses, grazers, are affected by the toxins in A. riparia, unknown how they affect T. thetis (red-necked pademelon)… there may be chronic disorders induced by regular consumption. (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000). Evidence of toxic properties affecting some mammals but impact on native fauna unknown. | M | ML |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | ‘The red-necked pademelon, Thylogale thetis, browsed extensively on A. riparia’ (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000). ‘Stock mostly avoid grazing the plant…’ (Barton et al. 2006). Sheep and horses are affected by the toxins (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000). It is not documented if this species provides a food source for pest animals. Evidence suggests it is avoided and/or toxic to some mammals but is also readily consumed by one mammal species. | M | L |

| 18. Provides harbor? | Branches intertwine producing a blanket effect, giving effectively 100% ground cover (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000). Due to the dense vegetative habit of this species it is likely to have the capacity to provide harbour to smaller pest animals. However, specific evidence about its capacity to provide harbour is not documented. | M | ML |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | ‘...spreading into pastures, reducing the carrying capacity significantly..’ (QLD NRW). Restricts movement of stock and has no feed value (Wilson & Graham 2000). Has toxic properties, with alcohol extracts of the plant killing sheep (Everist 1981) and consumption causing lung lesions in horses (Gibson & O’Sullivan 1984). ‘Stock mostly avoid grazing the plant…’ (Barton et al 2006). Could significantly reduce carrying capacity and may reduce stock health. Potential to reduce yield by >5%. | MH | MH |

| 20. Impact quality? | No information was documented to suggest this species would have an impact on agricultural product quality. | L | MH |

| 21. Affect land value? | The species is categorised as a class 4, Noxious Weed in NSW (NSW Gov. Gaz.166) and a class 3, noxious weed in Northern Territory (Wilson & Graham 2000). Its ability to significantly reduce carrying capacity (QLD NRW) and form dense stands (PIER) could lead to a minor decrease in land value in grazing situations. However, no information was specifically documented. | M | L |

| 22. Change land use? | Its ability to significantly reduce carrying capacity (NRW QLD) and form dense stands (PIER) could lead to a minor change to priority of land use in grazing situations. It is likely to also affect more the visual appeal of the land. | ML | M |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | ‘…restricts movement of stock and machines.’ (Wilson & Graham 2000). Restricted access may increase labour & time to undertake stock movement and harvesting. Minor increase in cost of harvesting. | M | MH |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | No evidence found to suggest this species is a disease host or vector. | L | MH |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | ‘Seed germination commences with the onset of rains…’ (Tripathi & Yadav 1987). ‘Germinate at the start of the wet season and seedlings grow rapidly’ (Wilson & Graham 2000). Requires natural seasonal disturbances, eg. Rainfall. | MH | H |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | ‘Tolerant of deep shade…’ (NZPCN) ‘…a shade tolerant plant,’ (Parsons & Cuthbertson 1992). Shade tolerant and likely to establish under a moderate canopy. | MH | MH |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Subtropical and tropical rainforests (NZPCN). ‘…dry disturbed habitats to mesic and wet forest,’ (PIER). ‘…stream banks and clearings in rainforest and pasture.’ (Weeds Aust.). The only exotic species found in the Hakgala Strict Nature Reserve, Sri lanka in upper montane rainforest at 2000m (Rathnayake & Jayasekera 1998). Occurs in poorly managed pasture, wetlands and streambanks and is common beside walking tracks and along river systems in native forests. (Barton et al 2006). Establishes in highly disturbed areas but also minor disturbed natural ecosystems such as, wetland, riparian, and rainforest. | MH | H |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Erect or sprawling many-stemmed herb to subshrub to 0.5-1.5 m (NZ PCN). Height appears quite variable: ‘…40 to 100cm high but usually 40 to 60 cm…’ (Parsons & Cuthbertson 1992). Life form: Other | L | MH |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | ‘Particular reference is made to the allelopathic properties of… Eupatorium riparium…’(Parihar & Kanodia 1987). Extracts and leachates of fresh leaves and litter suppressed germination and growth of two Galinsoga species. (Rai and Tripathi 1984). ‘Chemicals from the leaf-litter suppress the growth of other plants, eg. native species…’ (Wilson & Graham 2000)’. Evidence of allelopathic properties seriously affecting some plants. | MH | MH |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Browsing and incidental damage by the red necked pademelon, Thylogale thetis breaks up broad stands of A.riparia but the selective manner in which it eats the leaves may be an indication of toxin detection. (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000). ‘In all areas, regrowth of browsed plants was evident in the development of new branches’ (Zancola Wild & Hero 2000). Tolerant of grazing (NZ PCN). ‘Stock mostly avoid grazing the plant…’ (Barton et al 2006). ‘...it has no feed value.’ (Wilson & Graham 2000)’. Consumption by some individual species is documented but mostly it appears to be avoided as a food source and tolerant to herbivory. | MH | M |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | ‘ Seedlings, growing rapidly, become firmly established…’ (Parsons & Cuthbertson 1992). ‘Germinate at the start of the wet season and seedlings grow rapidly’ (Wilson & Graham 2000). Rapid growth rate. | H | MH |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | ‘Tolerant of deep shade and damp, damage and grazing, salt, most soils’ (NZPCN) ‘Its southward dispersal is most probably limited due to sensitivity to frost, and it’s northward dispersal by high temperatures’ (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000). Occurs in wetlands (Barton et al 2006). Showed increased population density and longevity of individuals after burning. (Tripathi & Yadav 1987). Sensitive to drought and frost, tolerant of fire, salt and possibly waterlogging. Tolerant to two stresses and susceptible to two. | ML | MH |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | ‘ …reproduces by seed and spreads also vegetatively by stem layering,’ (Weber 2003). Vegetative & seed reproduction. | H | MH |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | ‘Can produce 7000-10000 seeds per season’ (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000). Above 2000. | H | H |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | A very low percentage of viable seeds were recovered from the soil seed bank and the survival of seeds declined rapidly over a 2-year period (Yadav & Tripathi 1982). Unlikely that greater than 25% of seeds would survive 5 years. | L | H |

| 12. Reproductive period? | Colonies increase in size and density by layering, forming a mat of interwoven stems (Parsons & Cuthbertson 1992) ‘… covering whole mountainsides.’ (Parsons & Cuthbertson 1992). ‘…plants intertwine producing a blanket affect, giving effectively 100% groundcover’ (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000).‘Dense stands of Mistflower…’ (PIER). Evidence of self-sustaining dense populations possibly forming monocultures. | H | H |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | ‘The rapidly growing seedlings may reproduce within 8-10 weeks’ (Weber 2003). Time to reach reproductive maturity is < 1 year. | H | MH |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | ‘…as impurities in agricultural produce, in sand and gravel used in roadworks, and in mud sticking to animals, machinery, other vehicles, clothing and footwear (Parsons & Cuthbertson 1992) ‘...seeds can be dispersed by wind and water or by becoming attached to animals.’ (Zancola, Wild & Hero 2000). Topped by a “parachute” of fine white hairs that aid in wind dispersal’ (Wilson & Graham 2000). Propagules spread by wind, water animals and light vehicular traffic. | MH | H |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | Due to the number of dispersal mechanisms described above and as a riparian species often growing close to running water, it is very likely that some propagules will disperse greater than one kilometre. | H | MH |

References

Australian Weeds Committee, Weeds Australia (Weeds Aust.), viewed 23rd October 2006, www.weeds.org.au

Barton, J, Fowler, SV, Gianotti, AF, Winks, CJ, de Beurs, M, Arnold, GC & Forrester, G. 2006, ‘Successful biological control of mist flower (Ageratina riparia) in New Zealand: agent establishment, impact and benefits to the native flora’ (accepted manuscript). Landcare Research, New Zealand.

Department of Natural Resources & Water, Queensland Government (NRW QLD) 2006, Pest Series, Department of Natural Resources & Water, Land Protection, Brisbane Queensland, viewed: 23 October 2006, www.nrw.qld.gov.au/factsheets/pdf/pest/pp20.pdf

Everist, SL. 1981, Poisonous Plants of Australia, Revised Edition, Angus & Robertson, Australia.

Gibson, JA & O’Sullivan, BM. 1984, ‘Lung lesions in horses fed mist flower (Eupatorium riparium)’, Australian Veterinary Journal, vol. 109, no. 8, p. 271.

New South Wales Government Gazette No. 166 (NSW Gov. Gaz.166), 2005, Special Supplement: 11796. Weed Control Order No. 19.

New Zealand Plant Conservation Network (NZ PCN) 2005, New Zealand Plant Conservation Network, Wellington, New Zealand, viewed: 24th October 2006, www.nzpcn.org.nz

Pacific Island Ecosystem at Risk (PIER) 2005, Hawaii Ecosystem at Risk, viewed: 12th September 2006, http://www.hear.org/Pier/wra/pacific

Parihar, SS & Kanodia, KC. 1987, ‘Beware of the Exotic Weeds’, Indian Farming, vol. 37, no. 9, pp 24-25.

Parsons, W.T. & Cuthbertson, E.G. 1992, Noxious weeds of Australia, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood.

Rai, JPN & Tripathi, RS. 1984, ‘Allelopathic effects of Eupatorium riparium on population regulation of two species of Galinsoga and soil microbes’, Plant and Soil, vol. 80, no. 1. pp. 105-117.

Rathnayake, RMW & Jayasekera, LR. 1998, ‘Threatened endemic vegetation in the upper montane rain forest in Hakgala Strict Nature Reserve’, Sri Lanka Forester, vol. 23, no. 1 / 2, pp. 18-22.

Tripathi, RS & Yadav, AS 1987, ‘Population dynamics of Eupatorium adenophorum Spreng and Eupatorium riparium Regel in relation to burning’, Weed Research, vol. 27, pp. 229-236.

Weber, E. 2003, Invasive plant species of the world: a reference guide to environmental weeds, CABI Publishing, Wallingford.

Wilson, C & Graham, N., 2000. ‘Mistflower’, Agnote, 628, no. F80. Weeds Branch (Darwin), Department of Natural Resources, Environment and the Arts, Northern Territory, http://www.nt.gov.au/nreta/naturalresources/weeds/ntweeds/declared.html

Yadav, AS & Tripathi, RS. 1982, ‘A study on seed population dynamics of three weedy species of Eupatorium’, Weed Research, vol. 22, pp. 69-76.

Zancola, BJ, Wild, C & Hero, J-M. 2000, ‘Inhibition of Ageratina riparia (Asteraceae) by native Australian flora and fauna’, Austral Ecology, vol. 25, pp. 563-569.

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) 2006, Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, viewed: 29 November 2006, http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/

Barton, J, Fowler, SV, Gianotti, AF, Winks, CJ, de Beurs, M, Arnold, GC & Forrester, G. 2006, Successful biological control of mist flower (Ageratina riparia) in New Zealand: agent establishment, impact and benefits to the native flora (Accepted Manuscript). Landcare Research, New Zealand.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2006, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed: 12 September 2006,

http://www.gbif.org/

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) 2006, w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, viewed: 12 September 2006,

http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html

Real Jardin Botanico 2006, Proyecto ANTHOS, Database, http://www.programanthos.org/anthos.asp, viewed: 28 November 2006.

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.