Holm oak (Quercus ilex)

Present distribution

|  This weed is not known to be naturalised in Victoria | ||||

| Habitat: Germination of holm oak was restricted to shaded conditions” (Broncano et al 1998). “Montane holm oak forest” (Espelta et al. 1995). “Exposed to the typical Mediterranean dry period… during which only about 60-80 mm rainfall interrupt the dry, hot summer” (Lo Gullo & Salleo 1993). “440 mm of annual rainfall are required for these forests to persist… Considered as a model of Mediterranean sclerophylly” (Terradas & Savé 1992). Temperature at the study site ranged from 36°C and -5°C. “Frost is common from November to March” (Sala & Tenhunen 1994). Oaks “grow naturally in woodlands” (Spencer 1995). Found along the Black Sea Coast. “Grows well on a variety of substrata in the Mediterranean bioclimate (except, of course under too arid conditions)” (Barbero 1992). Quercus species are drought tolerant (Mendoza et al. 2006). Species with a deep root system adapted to take water from the depth (such as evergreen Quercus species) (Pausas 1999). “Succeeds in all soils except those that are cold and poorly drained…Very resistant to maritime exposure” (PFAF 1996-2008). | |||||

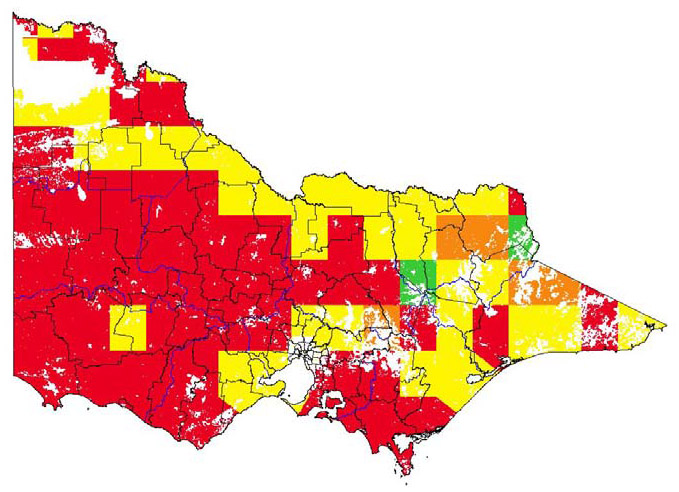

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Broadacre cropping; forestry; horticulture seasonal; pasture dryland; pasture irrigation Ecological Vegetation Divisions Coastal; heathland; grassy/heathy dry forest; foothills forest; rainforest; rocky outcrop shrubland; western plains woodland; alluvial plains grassland; ironbark/box; riverine woodland/forest Colours indicate possibility of Quercus ilex infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | “An evergreen tree growing to 25m by 20m at a slow rate” (PFAF 1996-2008). Could become a high nuisance value due to the size of width. People and/or vehicles access with difficulty. | MH | ML |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | “An evergreen tree growing to 25m by 20m at a slow rate” (PFAF 1996-2008). Some recreational uses may be affected due to the size of width. | MH | ML |

| 3. Injurious to people? | “Poisoning in children from chewing a few acorns need cause little worry before in the introduction the potato, acorns were a (starch-containing) food in times of emergency” (Pfander 1984). “Leaves are alternate, simple and leathery, with spiny, serrate margins” (Bodkin 1986). Not toxic to people but may cause some physiological issues from serrated leaf margins. | ML | ML |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | Species with a deep root system adapted to take water from the depth (such as evergreen Quercus species) (Pausas 1999). Quercus spp. has extensive root systems and do not like to be transplanted (Young 1999). May cause a moderate structural effect. | MH | ML |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Montane holm oak forest” (Espelta et al. 1995). “Seeds were germinated in nursery flats filled with calcareous sand” (Broncano et al 1998). “Considered as a model of Mediterranean sclerophylly” (Terradas & Savé 1992). Oaks “grow naturally in woodlands” (Spencer 1995). “Grows well on a variety of substrata in the Mediterranean bioclimate (except, of course under too arid conditions)” (Barbero 1992). Not described as aquatic. | L | M |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Montane holm oak forest” (Espelta et al. 1995). “Seeds were germinated in nursery flats filled with calcareous sand” (Broncano et al 1998). “Considered as a model of Mediterranean sclerophylly” (Terradas & Savé 1992). Oaks “grow naturally in woodlands” (Spencer 1995). “Grows well on a variety of substrata in the Mediterranean bioclimate (except, of course under too arid conditions)” (Barbero 1992). Not described as aquatic. | L | M |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | Species with a deep root system adapted to take water from the depth (such as evergreen Quercus species) (Pausas 1999). Quercus spp. has extensive root systems and do not like to be transplanted (Young 1999). Low probability of large scale soil movement. | L | ML |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | “An evergreen tree, it grows to a height of 25 m with a spread of 4 m” (Bodkin1986). Biomass may increase as this is such a large tree. | L | ML |

| 9. Change fire regime? | “Plant material, while it may accentuate the damage caused by fire, can also be used to slow or divert the fire…Deciduous hardwoods that are suitable include oaks (Quercus spp.)” (Cremer 1990). Could greatly change the frequency and/ or intensity of fire. | H | ML |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC = Grassy Woodland (E); CMA = Goulburn Broken; Bioregion = Victorian Riverina; VH CLIMATE potential. “The dominant species of most mature communities over large areas of the Mediterranean basin” (Terradas & Savé 1992). “An evergreen tree growing to 25 m by 20 m at a slow rate” (PFAF 1996-2008). Major displacement of some dominant species within a strata/layer (or some dominant species within different layers). | MH | M |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC = Warm Temperate Rainforest (R); CMA = East Gippsland; Bioregion = Highlands- Southern Fall; VH CLIMATE potential. “The dominant species of most mature communities over large areas of the Mediterranean basin” (Terradas & Savé 1992). “An evergreen tree growing to 25 m by 20 m at a slow rate” (PFAF 1996-2008). Major displacement of some dominant species within a strata/layer (or some dominant species within different layers). | MH | M |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC = Heathy Woodland (LC); CMA = Glenelg Hopkins; Bioregion =Greater Grampians; VH CLIMATE potential. “The dominant species of most mature communities over large areas of the Mediterranean basin” (Terradas & Savé 1992). “An evergreen tree growing to 25 m by 20 m at a slow rate” (PFAF 1996-2008). Major displacement of some dominant species within a strata/layer (or some dominant species within different layers). | MH | M |

| 11. Impact on structure? | “The dominant species of most mature communities over large areas of the Mediterranean basin” (Terradas & Savé 1992). “An evergreen tree growing to 25 m by 20 m at a slow rate” (PFAF 1996-2008). Minor effect on >60% of the layers or major effect on <60% of the flora strata. | MH | M |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | No information mentions any VROT species. | MH | L |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | No information mentions any threatened species. | MH | L |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | No information found. | M | L |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | “In Spain, acorns are consumed by many species of birds and mammals…The main mammalian predators in the Lerma region are Wild Board, Sus scrofa, and Wood Mice, Apodemus sylvaticus, While Tits, Chaffinches, Wood Pigeons, Robins, Nuthatches, and Jays are potentially the main avian predators” (Santos and Telleria 1997). “In most years it is normal for animals, particularly horses to eat acorns as a highly nutritious pre-winter feed, sever poisoning may occur…Pigs have been poisoned by excessive quantities of acorns, but such an occurrence is very rare, These animals usually thrive on them (Cooper and Johnson 1984). Could provide some assistance in either food or shelter to desirable species. | MH | ML |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | “Several species are known to be toxic; Kingsbury suggests that all should be regarded as potentially toxic…Experimental feeding of fresh, frozen, or dried blossoms, buds, leaves, and twigs of Q. havardii caused disease in cattle, sheep, goats, rabbits, and guinea pigs” (Keeler et al. 1978). Poisoning can occur in horses, cattle, sheep and pigs (Cooper and Johnson 1984). “Leaves, young shoots, buds and acorns are poisonous and with a bitter taste; also allergenic. Can be toxic to domestic pets. Also toxic to livestock. Toxins Tannins. (Shepherd 2004). Toxic, and causes allergies. | H | M |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | “In Spain, acorns are consumed by many species of birds and mammals…The main mammalian predators in the Lerma region are Wild Boar, Sus scrofa, and Wood Mice, Apodemus sylvaticus, While Tits, Chaffinches, Wood Pigeons, Robins, Nuthatches, and Jays are potentially the main avian predators” (Santos and Telleria 1997). “In most years it is normal for animals, particularly horses to eat acorns as a highly nutritious pre-winter feed, sever poisoning may occur…Pigs have been poisoned by excessive quantities of acorns, but such an occurrence is very rare, These animals usually thrive on them (Cooper and Johnson 1984). Supplies food for serious pest (e.g. pigs), but at low levels. | MH | M |

| 18. Provides harbour? | “An evergreen tree, it grows to a height of 25 m with a spread of 4 m” (Bodkin1986). Doesn’t provide harbour for serious pest species, but may provide for minor pest species. | ML | ML |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | “Oak poisoning in cattle occurs in many parts of the world and is of major economic importance in some places…Death may occur suddenly during a convulsion…Eight sheep died after grazing young oak shoots” Poisoning can occur in horses, cattle, sheep and pigs (Cooper and Johnson 1984). “Several species are known to be toxic; Kingsbury suggests that all should be regarded as potentially toxic…Experimental feeding of fresh, frozen, or dried blossoms, buds, leaves, and twigs of Q.havardii caused disease in cattle, sheep, goats, rabbits, and guinea pigs” (Keeler et al. 1978). Could be a major impact on quantity of produce (e.g. 5-20%). | MH | M |

| 20. Impact quality? | “Oak poisoning in cattle occurs in many parts of the world and is of major economic importance in some places…The milk from lactating animals is often bitter and unusable for any purpose” (Cooper and Johnson 1984). Serious impacts on quality. Produce rejected for sale or export. | H | M |

| 21. Affect land value? | Not enough information. | M | L |

| 22. Change land use? | “The very slow growth rate of oak trees… The duration of this life cycle (up to 800 years)” (Pulido et al. 2001). Not likely to change land use as it is a slow growing plant and the impacts of its presence could be minimised. | L | ML |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | “Jays dispersed significantly more acorns into afforestations… 94% of the caches made by jays were made under pines” (Gomez 2003). “Many Mediterranean forests (e.g. some Q. ilex forests) are composed of multiple stemmed trees (coppices) resulting from fire or logging” (Pausas 1999). “Oak poisoning in cattle occurs in many parts of the world and is of major economic importance in some places…The milk from lactating animals is often bitter and unusable for any purpose” (Cooper and Johnson 1984). Slightly more time and labour may be required to remove acorns, seedlings, etc. to prevent contamination. Minor increase in cost of harvesting. | M | ML |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | “Chestnut blight: Cryphonectria parasitica (Murr.) Barr. …Hosts: chestnut, oak …Entire trees may die if the trunk is girdled. Likely pathway: nuts/seeds, nursery stock, bark, lumber and wood packaging material including dunnage. Potential impact: one of the most serious plant diseases in North America. Within 50 years the disease spread to the extremes of the natural range of the American chestnut, destroying the economic and aesthetic value of one of America’s most versatile trees. (Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry- Australia 2001). Host to major and severe disease or pest of important agricultural produce. | H | M |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | “Canopy closure seems to promote seedling germination” (Espelta et al. 1995). “Shading increased germination in oak…Germination of holm oak was restricted to shaded conditions” (Broncano et al. 1998). Requires specific environmental factors that are not part of an annual cycle to germinate. | L | MH |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | “Shade-tolerant during its early life cycle. It is unable to recruit when exposed to full sun-light and high temperatures” (Gomez 2004). “RGR [relative growth rate] decreased and mortality increased under full light conditions for holm oak” (Broncano et al. 1998). Requires more specific requirements to establish. | ML | H |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | “Older seedlings show a tendency towards increasing survival under some degree of canopy closure…Sprouters might require long disturbance-free intervals and canopy gap formation for successful reproduction and potential population expansion…(Bran et al. 1990) also indicate that holm oak shows better germination rates under tree cover than in clearings or clear-cuts” (Espelta et al. 1995). Not enough information to indicate which vegetation types it will establish in. | M | L |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | “Holm Oak tree size” (Santos & Telleria 1997). Other. | L | H |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | “Self-allelopathic effects upon germination in holm oak” (Broncano et al. 1998). Minor allelopathic properties. | ML | M |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | “So propagation might mainly occur by vegetative sprouting in patches with heavy acorn predation” (Santos and Telleria 1997). Consumed and recovers slowly. Reproduction strongly inhibited by herbivory, but still capable of vegetative propagule production; weed may still persist. | ML | H |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | “Several of the cool-temperate species grow more quickly in the relatively warm SE Australian climate” (Spencer 1995). Maximum growth rate less than many species of the same life form. | ML | ML |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | “They survive and re-sprout properly after fire” (Pausas 1999). “Drought tolerant species such as Quercus spp.” (Mendoza et al. 2006). “The species grows between 700 and 1200 m elevation and it can be found up to 1800 m” (Lo Gullo and Salleo 1993). “440 mm of annual rainfall are required for these forests to persist” (Terradas & Savé 1992). Very resistant to maritime exposure” (PFAF 1996-2008). “Grows well in an exposed position, particularly on the coast” (Young 1999). Oaks have “resistance to water and most pests that destroy wood” (Macoboy 2006). Tolerant to fire and drought. Maybe tolerant of frost and minimal salinity. Possibly some tolerance of waterlogging. | ML | ML |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | “Holm oak is capable of both sexual and vegetative regeneration” (Santos and Telleria 1997). Both vegetative and sexual reproduction. | H | H |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | Maximum viable fruit of Q. ilex in Dehesa plot is 10,767 (Pulido 2005). “Plant species with large seeds, including oaks…show synchronized production of large fruit crops, which is termed mast seeding” (Herrera 1995). Greater than 2,000. | H | ML |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | No information found. | M | L |

| 12. Reproductive period? | “The duration of this life cycle (up to 800 years)” (Pulido et al. 2001). Likely that a mature plant could produce viable propagules for more than 10 years. | H | ML |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | No information found. | M | L |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | “It was impossible to me to distinguish the jay-produced caches from cache made by wood-mice” (Gomez 2003). “In Spain, acorns are consumed by many species of birds and mammals…The main mammalian predators in the Lerma region are Wild Board, Sus scrofa, and Wood Mice, Apodemus sylvaticus, While Tits, Chaffinches, Wood Pigeons, Robins, Nuthatches, and Jays are potentially the main avian predators” (Santos and Telleria 1997). Potential for other species found in Australia to disperse seeds. Bird dispersed seeds or has edible fruit that is readily eaten by highly mobile animals. | H | ML |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | “Long-distance events have been reported for some plant species, many of them dispersed by jays, which can move acorns and nuts over several kilometres” (Gomez 2003). Possible that other bird species in Australia may display the same behaviour, hence it could be very likely that at least one propagule will disperse greater than one kilometre. | H | ML |

References

Agricultural, Fisheries and Forestry - Australia. (2001) Forests and Timber: A Field Guide to Exotic Pests and Diseases. Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service, the National Office of Animal and Plant Health, and the Ministerial Council on Forestry, Fisheries and Aquaculture - Standing Committee on Forestry, Canberra.

Barbero M, Loisel R, and Quezel P. (1992) Biogeography, ecology and history of Mediterranean Quercus ilex ecosystems. Vegetatio. 99-100: 13-34.

Bodkin F. (1986) Encyclopaedia Botanica: The Essential Reference Guide to Native and Exotic Plants in Australia. Angus & Robertson.

Bran D, Lobréaux O, Maistre M, Perret P, Romane G (1990) Germination of Quercus Ilex and Quercus pubescens in Q. ilex coppice. Vegetatio 87: pp 45-50

Brasier C. (2003) Phytopthoras in European forests: Their rising significance. Sudden Oak Death Online Symposium. Available at: www.apsnet.org/online/SOD (Web site of The American Phytopathological Society).

Broncano M.J, Riba M, and Retana J. (1998) Seed germination and seedling performance of two Mediterranean tree species, holm oak (Quercus ilex L.) and Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.): a multifactor experimental approach. Plant Ecology. 138:17-26.

Cooper MR and Johnson AW. (1984) Poisonous Plants in Britain and their Effects on Animals and Man. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office. London.

Cremer K.W. (1990) Trees for Rural Australia. Inkata Press Pty.Ltd. Melbourne, Sydney.

Espelta J.M, Riba M, and Retana J. (1995) Patterns of seedling recruitment in West-Mediterranean Quercus ilex forests influenced by canopy development. Journal of Vegetation Science. 6: 465-472.

Gomez J.M, Valladares F, and Prerta-Pinero C. (2004) Differences between structural and functional environmental heterogeneity caused by seed dispersal. 18: 787-792.

Gomez J.M. (2003) Spatial patterns in long-distance dispersal of Quercus ilex acorns by jays in a heterogenous landscape. Ecology 26:573-584.

Herrera J. (1995) Acorn predation and seedling production in low-density population of cork oak (Quercus suber L.). Forest Ecology and Management. 76: 197-201.

Keeler R.F, Van Kampen K.R. and James L.F. (Edt) (1978) Effects of Poisonous Plants on Livestock. Acedemic Press, New York.

Lo Gullo M.A. and Salleo S. (1993) Different vulnerabilities of Quercus ilex L. to freeze- and summer drought-induced xylem embolism; an ecological interpretation. 16: 511-519.

Macoboy S. (2006) What Tree Is That? 3rd Edn. New Holland Publishers, Sydney.

Mendoza I, Castro J, and Zamora R. in Price F.M. (Edt.) (2006) Global Change in Mountain Regions. Sapiens Publishing; Duncow, Kirkmahoe, Dumfrieshire.

Pausas J.G. (1999) Mediterranean vegetation dynamics: modelling problems and functional types. Plant Ecology. 140: 27-39.

Pfander F. (1984) A Colour Atlas of Poisonous Plants: A Handbook for Pharmacists, Doctors, Toxicologists, and Biologists. Wolfe Publishing LTD, London.

Plants for a Future. (PFAF) (1996-2008) Edible, Medicinal and Useful Plants for a Healthier World. Available at: http://pfaf.org/ (verified 09/09/2009).

Pulido F.J, Diaz M, Hidalgo de Trucios S.J. (2001) Size structure and regeneration of Spanish holm oak Quercus ilex forests and dehesas: effects of agroforestry use on their longterm sustainability. Forest Ecology and Management. 146: 1-13.

Pulido F.J. and Diaz M. (2005) Regeneration of a Mediterranean oak: A whole-cycle approach. Ecoscience. 12(1): 92-102.

Sala A. and Tenhunen J.D. (1994) Site-specific water relations and stomatal response of Quercus ilex in a Mediterranean watershed. Tree physiology. 14: 601-617.

Santos T. and Telleria J.L. (1997) Vertebrate predation on Holm Oak, Quercus ilex, acorns in a fragmented habitat: effects on seedling establishment. Forest Ecology and Management. 98: 181-187.

Shepherd RCH. (2004) Pretty But Poisonous. Plants Poisonous to People, An Illustrated Guide for Australia. RG & FJ Richardson. Meredith. Terradas J. and

Savé R. (1992) The influence of summer and winter stress and water relationships on the distribution of Quercus ilex L. Vegetatio. 99-100: 137-145.

Spencer R. (Ed.) (1997) Horticultural Flora of South-Eastern Australia Volume 2. Flowering Plants Dicotyledons Part 1. UNSW Press.

Terradas J and Save R (2004) The influence of summer and winter stress and water relationships on the distribution of Quercus ilex L. Vegetatio 99-100: pp 137-145

Young J. (1999) Botanica's Pocket Trees and Shrubs. Random House, Sydney.

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) (2009) Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, Available at http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/ (verified 01/09/2009).

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) (2009) Global biodiversity information facility, Available at http://www.gbif.org/ (verified 29/06/2009).

Integrated Taxonomic Information System. (2009) Available at http://www.itis.gov/ (verified 29/06/2009).

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) (2009) w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, Available at http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html (verified 29/06/2009).

United States Department of Agriculture. Agricultural Research Service, National Genetic Resources Program. Germplasm Resources Information Network - (GRIN) [Online Database]. Taxonomy Query. (2009) Available at http://www.ars-grin.gov/cgi-bin/npgs/html/taxgenform.pl (verified 29/06/2009).

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.