Soil Health Management Plan - Concept

| Introduction | Background | Soil health and the farming system | Lessons from the past | SHMP and other farm plans | The soil health management plan and the bigger picture Basic elements for a soil health management plan The elements | Soil inventory and interpretation | Assessment and monitoring | Planning and management | Business tools to assist the SHMP |  |

Introduction

The Soil Health Management Plan (SHMP) is a paddock by paddock, farm scale plan. It should be created by farmers for farmers. The SHMP is not an end in itself - it will only make sense and be applied if it is tied to business plans for the farm enterprise. Soil health interacts with crop type, climate and management to deliver dollars on farm from the sale of agricultural products.

Background

The DPI is significantly engaged in research, training and demonstration for various aspects of soil health. Most recently, funding from the Commonwealth Government1 and the Victorian Government2 has been used to deliver a project known as Healthy Soils. This project has been conducted in partnership with farmer groups in Western Victoria and South East South Australia. A primary objective of the Healthy Soils project has been to increase the knowledge and skills for soil management amongst farmers and their advisers. Two important outputs from the project are a series of training modules for different aspects of soil science and management, and a review of tools that can be used to assess soil health. The Soil Health Management Plan (SHMP) was conceived during the Healthy Soils project as an effective endpoint in which the information and tools could be applied on farm. The concept of a SHMP became the litmus test for relevance of information incorporated in the training modules - 'if it cannot be applied to management, it may be interesting but is useless'. Similarly, in the review of tools for soil assessment these were rated for their ease of use and their value to decision making. A pilot for soil health management planning commenced with members of the Mid Loddon Sub Catchment Management Group (MLSC) in 2008. The group received Commonwealth funding for 12 months under the Caring for our Country (CfoC) program and chose to incorporate the SHMP pilot within their CfoC project. DPI has worked in partnership with the MLSC to explore the capacity of two farmers to develop SHMPs for their farms. This report describes the SHMP concept and proposes a process for implementation based on progress with the pilot group so far.

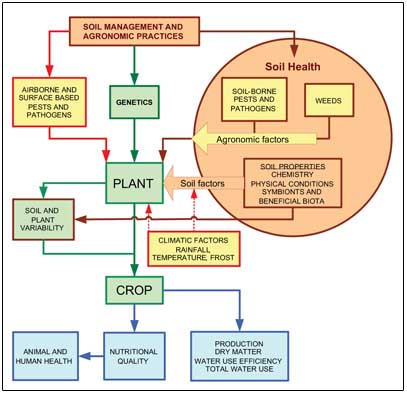

| Soil health and the farming system Soil health is not an end in itself. Soil, water, sunlight and air are the primary natural resources for agricultural production. Of these four, soil is the most complex component and is also highly sensitive to management. The term 'soil health' conjures up the sense of soil as living, productive and, by implication, something that can at times be unhealthy, incapacitated and unproductive. Soil is a finite resource on the farm. The farm enterprise is adapted to this resource in terms of the total land area of the farm and soil quality. These factors combine with season temperatures and water availability to determine the choice of produce, the production system, and the productive potential of the enterprise. Figure 1 illustrates some of these biophysical factors and relationships. The central vertical pathway in Figure 1 (green boxes) represents the primary agronomic choice (the crop or pasture that is to be grown) and the end result (blue boxes) as food quality, animal and human health, total production and production efficiency. Farming practices are applied to achieve the best result by managing soil conditions and weeds (brown circle) whilst responding to seasonal invasions of pests and pathogens and the vagaries of the climate and weather (yellow boxes not included in the soil health circle). Other important inputs associated with production, such as energy, labour, fertilisers, chemicals, machinery and infrastructure depreciation, are not represented in Figure 1. The success of the farming system may be indicated by gross production, the quality of the product and the efficiencies in production. Most of the annual enterprise decisions centre on the economics of production; machinery operation and replacement costs, seeds, fertilisers, chemicals and labour. These decisions are largely driven by experience of what has been successful in the past and the market opportunities for the coming season. Management of soil health is generally not an explicit part of this planning process but there are many aspects of the seasonal farm operations that have an impact on soil condition. Conversely, there are many soil related factors that have impacts on a successful outcome for the enterprise. Adopting soil health as another indicator of success is an important step in demonstrating a sustainable farming system that can also help achieve the bottom line business goals. |  Figure 1. Soil Health in the Agro-ecosystem |

Lessons from the past

Why should a landholder bother?

We have no previous experience of farm scale soil health planning, although there are similarities with whole farm planning. Whilst it is possible to create a framework for such a plan, implementation is the responsibility of the land manager. The challenge is to find or provide a driver that will motivate a land manager to adopt the ideas in the framework and make them part of the farm business planning activity. Economic benefits are not always clear enough for economics to be, at this time, a major driver, although many of the ‘alternative’ farming philosophies stress soil health as an objective that can benefit the economics of production through lowering the costs of inputs and raising the value of produce for specialised markets. There are considerable costs involved in changing farm equipment to adopt controlled traffic systems, for example, and there may be economic risks in reducing tillage or adopting zero till systems. We can point to successful examples that demonstrate the long term improvements to soil structure, and there are now some research results that show production benefits. In addition, lower fuel usage may be one of the most powerful drivers for change in traffic and tillage and this is likely to increase as oil becomes scarcer and more costly. An ecological conscience (caring for soil) and economics both play their part as drivers, but, at the present time, economics is the weaker of the two.

How should a soil health management planning framework be promoted?

There are many examples of programs to encourage farmers to adopt new practices. Some are more successful than others. The issue of drivers already discussed is an important one affecting success, but failure may occur because of the intellectual and emotional distance between the developer/s and the recipient/s. A ‘back-room’ approach to reviewing knowledge of a topic can produce credible output, but development of the knowledge into an application or tool to be used by others who have not been involved in the knowledge review is another matter.

Recent examples3 of soil quality and soil health knowledge extension stress the need to involve the farmers from the beginning. Unless the farmer ‘owns’ the plan it will never fully translate into enduring management.

SHMP and other farm plans

There are many other initiatives and projects driven by DPI that include soil management as an issue but not as the single focus. Some of these and their relationship to soil health management planning are described below.

SHMP and whole farm plans (WFP)

What is the difference between whole farm planning and a soil health management plan? Whole Farm Planning has been conducted for several decades and has its origins in the days of the Soil Conservation Authority4. The primary focus in whole farm planning is on farm layout, land class fencing, access and water reticulation. A WFP provides a sound approach to the natural resource 'infrastructure' of the farm. It should take account of water flow across the landscape, management of any erosion hazard, establishment of shelter belts and protection of native vegetation remnants.

SHMP and FarmPlan21

The most recent DPI advice on whole farm planning is part of the FarmPlan21 program conducted by Farm Services Victoria Division (FSV).

FarmPlan21 is described as 'Whole Farm Planning for the 21st Century' and defines a WFP in the following way:

"A Whole Farm Plan develops short term and long term goals based on the aims of the farming family or operation. Primarily the plan is to simplify management, improve productivity and include biodiversity and ecological issues in farm decision making. It takes into account livelihood, lifestyle and landscape to ensure sustainability of all three."

Using this definition as a model, we can define a SHMP:

"A Soil Health Management Plan (SHMP) develops short and long term goals based on the purposes of the farm business and the capacity to invest in improving soil management and thereby soil health. Soil is recognised as the primary natural resource supporting the farm business. The plan should take account of soil capability on the farm, current soil condition and requirements for management. A SHMP integrated with the farm business is used in consideration of crop choices, tillage, traffic, grazing management, machinery purchases, and inputs to maintain soil fertility (chemical, biological and physical), manage disease and reduce weeds."

SHMP and environmental management action planning (EMAP)

Another project that can provide a platform for development of SHMPs is environmental management action planning (EMAP) that has been delivered to farmers in a partnership between DPI, DSE and the Mallee region catchment management authority (MCMA). The EMAP process is also described as 'environmental whole farm planning'.

SHMP and eFARMER

eFARMER is a web-based application which supports the capture, viewing and sharing of natural resource management information across farms, landscapes and catchments. It has been developed by DPI and DSE working closely with a number of CMAs. Because of its links to Victorian government datasets eFARMER has a lot of potential for use in building soil health management plans, at least in providing some context for soils and geology. The scale of available soil maps is too coarse for farm planning and can only provide a regional indication of a soil inventory. Access to aerial photography, property boundaries and satellite data are the most useful aspects of eFARMER for development of SHMPs but not many farmers in the pilot group have equipment or confidence to take advantage. However, as computer literacy in the farming community grows and internet connectivity becomes faster and cheaper eFARMER may be more readily adopted. At this stage in the Healthy Soils project no single computer based system has been advocated.

SHMP and environmental best management practices program (EBMP)

The environmental best management practices program (EBMP) is a system used for self-auditing of practices on the farm. Participants rate themselves against management of a range of practices that include soils, water, vegetation, animals, chemicals, waste, etc. The SHMP would fit well into the EBMP by fulfilling the high level 'tick' for soil management practices. EBMP workbook can be a component in an environmental management system (EMS).

SHMP and environmental management systems (EMS)

The elements of an EMS are really the same as those found in WFPs, EBMPs and a SHMP. The difference between a true EMS and the other approaches is compliance to any documented industry standards under ISO 14001. This entails record keeping, monitoring, and auditing by a third party. Legal obligations for soil management are fairly limited but have been documented for Victoria in a DPI publication Soil Management, one of a series of 6 publications for EMS5.

The soil health management plan and the bigger picture

Soil health is important for sustainable farming because a healthy soil performs the functions that are expected of it. Annual maintenance costs to restore soil to a functionally healthy state can be avoided - e.g. changing from cultivation practices to zero tillage and controlled traffic systems reduces fuel costs and maintains soil structure. The costs of substituting management interventions for services that soil could provide can also be reduced or eliminated - e.g. soilborne disease management. There is also a bigger picture, beyond the farm.

Environmental impacts of inadequate soil management include groundwater contamination, surface water quality degradation (nutrients and turbidity), and destruction of infrastructure (e.g. erosion and deposition). On the positive side, a soil health management plan for a farm potentially enhances property value, provides evidence that can be used in environmental accreditation for 'clean and green' products, and even a basis for auditing practices against Carbon Pollution Reduction Schemes (CPRS).

At the state level, the number of farms, or land area, governed by SHMPs would be a worthy indicator of effective practice change in farm and soil management.

Basic elements for a soil health management plan

knowledge, skill and time of the farm manager allow. The main elements of the SHMP are soil inventory, monitoring, planning and management.

The elements

The basic elements of a soil health management plan answer three questions:

1. What do we have? = Soil inventory and interpretation.

2. How are things going? = Assessment and monitoring.

3. What needs to be done? = Planning and management.

Soil inventory and interpretation

This is the primary representation of soils on the farm and should include:

- Identification of major soil differences across the farm.

- Soil profile descriptions for full depth of major soils.

- A record of the critical differences between them.

- Ranking —best to worst (could depend on purpose).

- Any special considerations for management.

| Identifying the major soils Surface soil colour and textural differences are fairly obvious features, particularly when the soil is bare or is cultivated. Farmers will often use terms such as 'gray loam' or 'black clay' to describe their soil. Presence of cracking soils, stony areas, land subject to inundation, and general landform also provide indicators of soil differences. History of the farm, the order in which land was cleared, and the original vegetation cover can provide clues to the underlying soil and land quality. Recent technological innovations, particularly yield mapping, the use of ground based sensors (EM38) and interpretation of satellite imagery are proving invaluable for identifying soil-based production issues and for zoning paddocks for precision agriculture. The SHMP provides a framework for properly documenting these soil differences and issues. Soil profile descriptions Soil investigations must go deeper than the surface 10 cm. Total soil depth available for water storage and root growth can be extremely variable. Subsoil properties may restrict growth in ways that can be overcome by management or may be permanent features of the soil that have to be recognised and adapted to. If irrigation water is to be applied on the farm then knowledge of soil properties for the full profile (depth ~1-1.5 m) is essential. A soil auger or post hole digger may give sufficient information, particularly for confirming soil properties, but, ideally, a soil pit excavated by backhoe will give the best indication of soil horizons and structure (Figure 1). The main horizons should be sampled and sent away for chemical and physical analysis if funds permit. A well described soil profile supplemented by chemical and physical data provides a good reference site for the farm and for other landholders in the district. Critical soil differences Soil health (or soil quality) is described in terms of the capacity of the soil to perform critical functions such as: retain and store water for plant growth, resist erosion, and support traffic (animals and vehicles)6. Critical soil differences are the soil properties that affect these functions. Some of these properties are inherent to the soil and determine the soil quality, soil type or class of soil. These properties may change but only very slowly over decades, centuries or millennia (e.g. soil texture). It is these enduring inherent soil properties that should be described and mapped as part of the soil inventory. Other soil properties are changeable over the short term, during a season or over several management cycles. Such properties are dynamic, respond to management and also affect the soil's capacity to perform key functions (e.g. pH and soil structure affect availability of nutrients, soil air and water). The soil condition with regard to dynamic properties indicates soil 'health' and is therefore important for the assessment and monitoring elements in the SHMP. |  Figure 2. Full soil profile information is necessary. |

surface soil colour and texture, subsoil texture, total soil depth (or rooting depth), stoniness (rocks, gravels, buckshot), topsoil or A horizon thickness, surface drainage status, etc. The assistance of a soil specialist and training of farmers in some simple field methods to assess soil is necessary support for the development of a farm soil inventory.

Ranking the soil types

During the process of creating a soil inventory, comments should be recorded concerning the history and performance of different paddocks. A simple ranking of the soils from best performers to worst can do two things: it can indicate inherent differences in soil and land quality, and it may also highlight some management issues that have arisen in the past.

Special considerations for management

Special considerations for management will arise during the initial soil inventory and ranking. Issues for consideration include: erosion hazard, waterlogging and inundation, dispersive (sodic) soil, soil acidity, and structurally degraded soil.

Using available soil information

A large amount of soil information exists on the DEPI website, particularly in the Victorian Resources Online (VRO) pages7. Scanned soil survey reports and maps are available for download and are useful to gain a general idea of local soil types. However, most of the soil and land surveys have been conducted at regional scales that have insufficient spatial detail to be used to map soil at a farm scale. In addition to the soil survey reports there are several hundred examples of regional soil types complete with images, profile descriptions and analytical data. The VRO pages also include information on soil degradation processes and soil management. The web pages provide support for anyone developing a SHMP but direct consultation of a soil scientist will be needed for local interpretation and planning.

|  Figure 3. Sometimes expert help may be needed. |  |

Local farm knowledge and investigation will be required to complete a farm soil inventory and to create a soil map. Ultimately, this should be a fine scale soil map that has been interpreted in relation to management requirements for the different soil map units. Some whole farm plans (WFP) may already include a soil map. A SHMP can take this information to the next stage by assessing soil condition and managing

soil health.

Assessment and monitoring

The farmer needs to know how farming practices are affecting the soil. The soil inventory answers the question 'what's out there?' Assessment and monitoring should answer the question 'How well are things going?' A balanced program will include all of the following:

- Soil and plant sampling and laboratory analyses.

- Paddock walks and soil condition assessment.

- Evaluation of crop and animal production, quality and health.

| What factors should be monitored and how often should monitoring occur? There is no 'one size fits all' design for assessment and monitoring that can cover all soil and all farming systems. An appropriate assessment and monitoring routine depends on: land use, the practices and changes in practice, critical issues such as erosion, and the expected rate of change (e.g. soil carbon is slow to change whereas soil nitrogen changes rapidly). Guidelines for soil and plant sampling for analysis are provided by DEPI and commercial laboratories. Consideration should be given to timing, soil depth, tillage and fertiliser practices (e.g. banding, zero tillage). To monitor soil change, consistent methods must be applied in the field and laboratory from year to year. Surplus from large soil samples taken (more than is sent to the lab) can be held at the farm as reference samples in case methods or laboratories are changed. Samples for archiving should be thoroughly air dried and stored in water tight and vermin proof containers. |  Figure 4. Paddock walsk to inspect soil and crop condition |

| Paddock walks are opportunities for systematic visual and tactile assessment of soil to develop a familiarity with differences between paddocks, soils and seasons (Figure 4). These walks can be incorporated into crop monitoring and animal husbandry activities. Useful observations can be made of soil surface condition such as crusts, evidence of erosion, ponding of water, surface compaction etc. and supported by taking reference photographs. A simple penetrometer can easily be carried during a paddock walk to serve as a useful indicator of soil moisture conditions and subsoil physical strength (Figure 5). Farmers are increasingly adopting technology to assist in crop management. Yield monitors, satellite data, soil moisture sensors, and electromagnetic induction surveys are all examples of readily available technology. As with any new approach, expert help may be required for proper set up of equipment, training in applications, and interpretation of data. Site or farm specific calibrations should also be considered because soils are so diverse and variable. Soil moisture sensors may be deployed as portable meters to collect readings from many access points or as permanently installed sensors fitted with loggers to collect continuous soil moisture data. Efficiency in data collection can be supported by remote telemetry and directly downloading data from the loggers to the home computer. |  Figure 5. A simple penetrometer indicates soil strength and moisture content. |

| Crop yield, nutritional quality, animal production and animal health are seasonal indicators of the success of the farming system - soil management plays a significant role in these but there are other factors too. However, they can be used to guide soil investigations particularly if there is variation across the farm, or the outputs are less than expected given the season and the inputs used. Further information for soil health monitoring A soil health check ideally includes an assessment of soil physical condition, chemical fertility and biological functions. The Healthy Soils project's review of soil health tools provides a summary of useful methods. Also, the Healthy Soils training modules on understanding soil testing, soil structure, soil biology, organic matter, and soil water, are available for delivery to farmers and their advisers. Much of the material is available online through the DPI website. |  Figure 6. Training in use of equipment will be needed. |

| Planning and management Knowledge of soils, soil differences and soil condition needs to be translated into action - what management actions are required to maintain or improve soil condition and get the best from the soil? Crops and livestock Profitable production of food and fibre is the primary business goal. The aim of a SHMP is to align soil management with this goal. Decisions about crop type, rotations, and stock management all have an impact on, and are affected by, soil health. Crops are not all equal in terms of their fertility requirements, rooting depth or potential to protect soil. Hard hoofed animals can readily cause damage to soil that will impact subsequent plant growth (Figure 7 and Figure 8). |  Figure 7. Hard hoofed animals can readily cause damage to soil. Compaction by sheep treading on moist unprotected ground. |

| Grazing and cropping combinations must be carefully managed. Timing and sequencing of crop and stock operations, paddock by paddock, must not be left to chance but should be planned to achieve triple benefits for crop, stock and soil. Soil amendments Amendments such as fertilizers, lime, gypsum, composts, and feed supplements are major business expenses. It is essential to know where and when these amendments are needed, the amounts that should be applied, and their potential economic benefits. Conversely, the cost and penalties should also be known for not using appropriate amendments at the right time, in the right place and at the best rates. The business strategy for amendments must be based on good knowledge of the soil inventory, crop history, and soil testing. Tillage and traffic management |  Figure 8. Impact on following crop along a stock track created during the pasture phase. |

Decisions regarding tillage are critical for the business and for soil health. Fuel, machinery depreciation and implement wear are significant costs. A SHMP should account for differences in soil conditions and how tillage affects soil structure. It is much easier to degrade soil structure with tillage than it is to build good structure. Evaluation of existing equipment, condition, purpose and performance is an essential component of the SHMP.

Control of traffic across soil is also an important management tool for soil health. Soil becomes strong enough to support the loads imposed on it. Dry soil is strong - moist soil is weak. Dense soil is strong - loose soil is weak. Loose moist soil is good for plants, dense dry soil is good for supporting wheeled vehicles. A healthy soil for supporting traffic is not a healthy soil for growing crops, and vice-versa.

The simplest form of controlled traffic is to only put traffic on paddocks when soil structural damage is likely to be low. Fully developed controlled traffic confines traffic to consistent routes or tramlines, is managed by GPS guidance systems, and has machinery axle widths optimised to minimise the

trafficked area. Changing from uncontrolled to controlled traffic farming is therefore costly and needs to be planned in the business time frames for machinery replacement.

Adoption of minimum tillage and even zero tillage systems is increasing in Victoria. Controlled traffic farming has not yet been widely adopted but the efficiencies in fuel usage, management of inputs, and demonstrated yield benefits should serve to encourage rapid change in traffic management.

Changes in the NSW Cotton industry - a SHMP model

In the NSW irrigated cotton industry, as many as 14 different tillage operations per year used to be involved. Soil compaction and other aspects of soil structure decline were recognised as having a severe impact on cotton production and the costs of production. In the late 1980s considerable effort was devoted to simultaneously solving the soil and business problems. Now reduced tillage, controlled traffic, paddock zoning and soil monitoring are all integrated and provide a good model of a SHMP for that industry9.

| SHMP planning cycle The principal elements of the SHMP can be summarised diagrammatically (Figure 9) as an application of a standard planning cycle (plan-implement-review-improve). Knowledge of soil differences on the farm, and their responses, may change as experience is gained through implementation of the SHMP. The original inventory of soils and map may therefore also be modified. Business tools to assist the SHMP There are many products on the market that can assist in planning farm business activities, in particular for maintaining financial records and for financial planning. The DPI's AgriGater10 software is useful for running a variety of scenarios across the farm to evaluate costs and potential gross margins. It allows paddock by paddock analysis and is therefore well suited to incorporation in a SHMP and management of different soils or soil zones in a paddock. Machinery replacement costs are incorporated in the program, so plans for conversion of sowing equipment or standardisation of axle widths in a move to controlled traffic can be included in a scenario. |  Figure 9. SHMP Planning Cycle |

Mapping software that can incorporate data layers (land parcels, air photographs, geology, soil, etc.,) is an essential tool. There are many products available that can be used. These may be served via the web such as the DSE's eFarmer, or they may be stand-alone products with different degrees of functionality. At this time, most farmers would require a level of training to use such software and would be best served by having access to a provider who is able to process GIS data and supply appropriate hard copy maps.