7 Frameworks for decision-making and soil health

Back to: Soil health for Victoria's agriculture - context, terminology and concepts

7.1 Application of the Steinitz framework to soil health | 7.2 Integration of issues for soil quality, an example | 7.3 Soil health and the delivery of knowledge | 7.4 Stakeholders in soil health

Although not a goal in itself, soil health affects all areas of society through food and fibre production and relationships to environmental health. There are many papers now in the literature that present this standpoint (for example, Karlen et al. 2003; Doran 2002) as well as those that refute the value of the concept (Sojka and Upchurch 1999). The debate on both sides is driven by the recognition of complexity, on the one hand leading to arguments that ‘soil quality is humankind’s foundation for survival’ (Karlen et al. 2002) and, on the other hand, that the concept is too vague, cannot be quantified and raises more questions than can be answered. Definition of terms (Section 2) and agreement concerning their meaning is a necessary starting point in resolving differences. From this starting point we need frameworks that support the concept of soil health and enable its integration into planning and management activities. Three examples are given here: a decision making framework (after Steinitz 1993, Section 7.1), integration of soil quality objectives (Section 7.2), and delivery of knowledge (Section 7.3). These examples are followed by a simple presentation of the diversity of stakeholders and issues concerned with soil health (Section 7.4).

Soil management is carried out on the basis of judgements that range from those that are based on trust and tradition (things have always been done that way) to those that are scientifically informed. Management may also be based on other judgements that are neither blind, in the sense of following a tradition, nor scientific, but are based on ethical or philosophical views about what is ‘good’ for the soil.

7.1 Application of the Steinitz framework to soil health

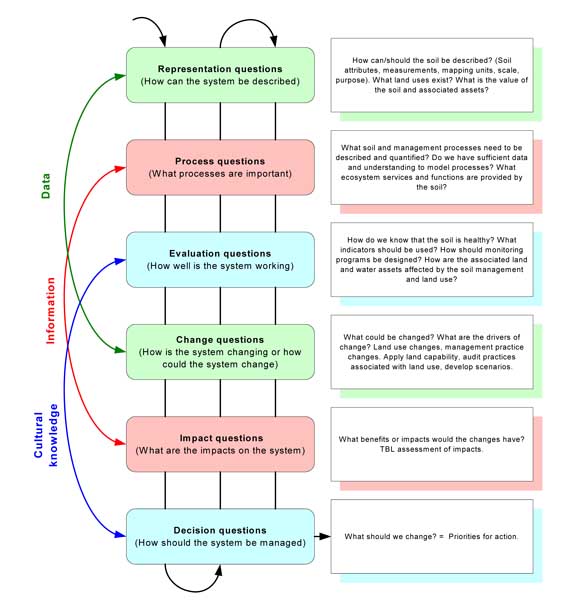

A systematic approach to the data, information and knowledge required for soil health management can be adapted from the landscape design framework of Carl Steinitz (1993). This framework is illustrated in Figure 8. The framework identifies six types of questions, each of which is pertinent to decision making. Steinitz focuses his work on the use of GIS and the modelling needs for spatial decision making (landscape analysis, scenarios and design solutions) but the framework structure has universal applicability. The logic of Steintitz’s approach to landscape design has been applied to soil health in Figure 8.

A simple sequence is as follows. The soil system must be described by appropriate qualities (attributes); the system must be understood in terms of its dynamics (processes and functions); and it must be evaluated with regard to how well it is working (functional capacity, monitoring and indicators). The system and its management can be changed or may be changing because of external influences (change and scenarios), and this is an important area for modelling that is linked to understanding the differences that the changes may make to the soil system (impact). Decisions are informed by the sequence described but may be tempered by a lack of sufficient data, information or knowledge.

The framework therefore provides a structure by which the adequacy of any of these may be judged. For example, if the representation questions concerning properties of the soil cannot be answered (such as insufficient data concerning particular soil parameters, scale of data or accuracy of mapping) then acquisition of data may be a priority. If the processes are not fully understood or cannot be modelled then empirical research into some aspect of soil system dynamics is required. If differences exist between judgements about how well the system is working then it may be necessary to defer to a political decision, or to pursue better knowledge of the link between indicators, functions and processes (a better monitoring program).

The process of using the framework is iterative. At any point it may be necessary to move back to a previous level to refine the data, information or knowledge for that level. Practically, the requirements for each level depend on the type of decision that is being made.

The six types of questions are a useful audit for any decision making process and have been used in section 8 to structure the discussion around recommendations for priorities for soil health data, information and knowledge.

Figure 8 A framework relating data, information and knowledge needs for decision making (after Steinitz 1993) illustrated with some example questions that need to be answered for management of soil health.

7.2 Integration of issues for soil quality, an example

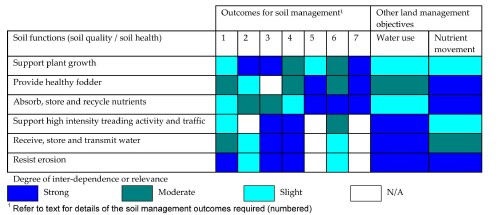

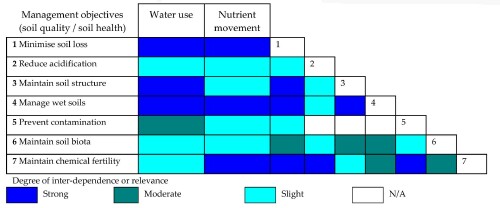

Soil health issues do not exist in isolation from each other or from other environmental issues. In fact, the soil health paradigm is useful because it places soil processes in this larger context. Examples of some of these inter–relationships are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10 based on requirements of the Australian dairy industry’s ‘Protection and Management of the Dairy Landscape Program’. This program had five subprograms, three of which were biophysical and had obvious synergies between them (Soil Management; Efficient water use; Nutrient management and movement). Six objectives had been set by the DRDC for soil management and a seventh (chemical fertility) was added:

1. Minimal loss of soil from dairy farms.

2. Either pasture systems that reduce rates of acidification, or the regular use of lime to correct pH.

3. Well–structured soils.

4. Specific practices and guidelines for managing wet soils.

5. Minimal build–up of chemical residues (or other undesirables such as sodium).

6. Large and active populations of soil biota so that organic matter breaks down rapidly, releasing nutrients for pastures, and maintaining soil structure.

7. Chemically fertile soils with appropriate balances of essential macro and micro nutrients to maintain quality of pasture and support animal health.

A soil quality approach was proposed which could provide an overarching framework for achievement of these objectives. Maintenance of six soil functions was seen as relevant to achieving these outcomes, as well as influencing the success of the water use and nutrient movement sub–programs (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Relationship between soil functions and some key soil management and environmental management objectives (MacEwan 1998).

Inter–relationships between the required soil management outcomes are illustrated in Figure 10. Detailed discussion of the inter–relationships between these outcomes and soil quality is given in MacEwan (1998).

Figure 10 Interrelationships between soil management objectives (example from priorities for the Australian dairy industry, MacEwan 1998)

7.3 Soil health and the delivery of knowledge

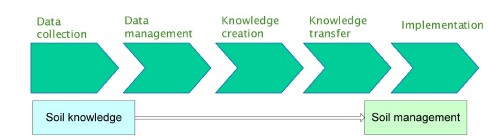

Knowledge creation, management and delivery is a complex subject in itself that can only be superficially addressed here. However, a useful framework is provided by viewing these as related in a business chain linking data collection, knowledge creation and implementation of knowledge (Figure 11).

Figure 11 Soil knowledge chain, from data collection to implementation of understandings.

Activities associated with this chain are provided in Table 4. Although represented as a linear process from data to implementation, in practice, the requirements for data, knowledge creation and management are driven by a need to implement better–informed management. There are parallels with the iterative process described in the context of the Steinitz framework (section 7.1).

Table 4 Phases in knowledge creation and implementation for soil health

Data Collection | Data Management | Knowledge Creation | Knowledge Transfer | Knowledge Implementation |

| Soil Surveys Site characterisations (reference sites) Yield data Soil condition | Storage and archiving Systems for data access. Custodians and accountability for data systems. | Description of processes and relationships. Conceptual and mathematical modelling. | Publications: reports, papers, technical notes, articles, fact sheets. Education, extension, training, demonstration | Research and trials based on new knowledge. Hypothesis testing. Practice change. (link back to data collection through monitoring and reporting) |

7.4 Stakeholders in soil health

There is a diversity of interest in soil health held by a range of stakeholders and these are summarised in Table 5. The issues or areas of concern have been separated into five topics: policy, ecosystem services provided by soil, understanding of soil processes, knowledge management, and primary production. Key stakeholders are the government departments (DPI and DSE), regional Catchment Management Authorities, farmers and farmer groups and the rural industry research corporations. Issues of concern for soil health are different for each of these groups and this has relevance to any communication planning with respect to soil health work.

Table 5 Stakeholder groups and relationship to areas of concern for soil health

Issue/area of concern | |||||

Stakeholder | Policies related to soil health or management | Soil as a functional component in the provision of Ecosystem Services/Catchment management | Understanding the soil resource, processes in the soil, and responses of soil to management | Knowledge Management and extension services | Production issues: using soil to make money |

| DPI | Soil Health Policy Framework development by Agriculture Policy Group. | Through production systems DPI has a role in determining sustainability of agriculture and the associated resource base (soil and water). | PIRVic is the lead body responsible for adding knowledge about soil process. Soil and Water platform is the lead platform but soil research will also occur in other areas. Work is often collaborative with other agencies (CSIRO, Universities). | Extension of soil knowledge primarily sits within CAS division in DPI. Knowledge management roles include those for text, data, maps etc., and reside principally in KIT branch and PIRVic. | Research and extension efforts are directed from DPI to develop more productive agricultural systems. |

| DSE | Catchment and Land Protection Act accountability. | Lead agency with respect to ecosystem services, land stewardship and catchment management. | Insofar as the knowledge will support decision making for catchment protection DSE is a stakeholder in this area. | Insofar as the knowledge will support decision making for catchment protection DSE is a stakeholder in this area. | Of no interest. |

| CMAs | No accountability for policy development. May implement policy. | Lead regional authority responsible for catchment management, condition and reporting. | In particular CMAs need to know how to set targets and monitor soil health for catchment condition reporting. | Through soil health strategies, action plans and monitoring activities, CMAs will disseminate and collect knowledge about soil health and soil management in their regions. | Of some interest wrt regional sustainability. |

| Farmers and farming groups | Minor importance. | Increasingly involved in catchment and landscape issues related to farming. | Through partnerships in research and demonstration projects, these groups are adding to the understanding of soil responses to management. | Main clients for knowledge management and knowledge supply for soil management. | Most significant stakeholders are those involved in soil based primary production systems. |

| RIRFs | Minor importance | Minor interest | Invest in research providers (government, universities and consultants) to acquire new knowledge about soil insofar as it affects the industry. | Invest in service providers. | Most significant decision makers for investment in research, development and extension activities. |