Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum)

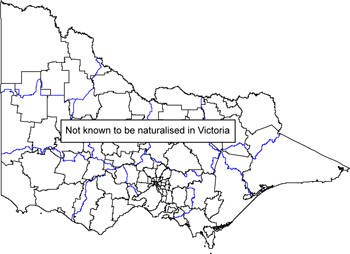

Present distribution

|  This weed is not known to be naturalised in Victoria | ||||

| Habitat: Native to North & Central America. Occurs in wet & dry soils (MBG 2006) Inhabits prairies, especially mesic to wet types, fresh/ brackish marshes, open oak/ pine woodlands, dunes, dry slopes, lakeshores & stream banks (Uchytil 1993; Freckman & Lelong 2005), roadsides & railway lines (MGB 2006; Forest Service 2002). Hardy to approx. 2300m (Denver Plants 2003) & grown successfully at 1350m in China (Ichizen et al 2005). Sown as pasture grass and for revegetating disturbed sites such as mine tailings (Parrish & Fike 2005). Listed as worldwide weed of cocoa plantations (OARDC 1998) & weed of rotation crops (Hafliger & Scholz 1980). Listed as present in Columbia, Argentina, Africa, Russia & SE Europe, India & Pacific Is. (Hafliger & Scholz 1980). Not known to be naturalised in Australia (Randall 2004). | |||||

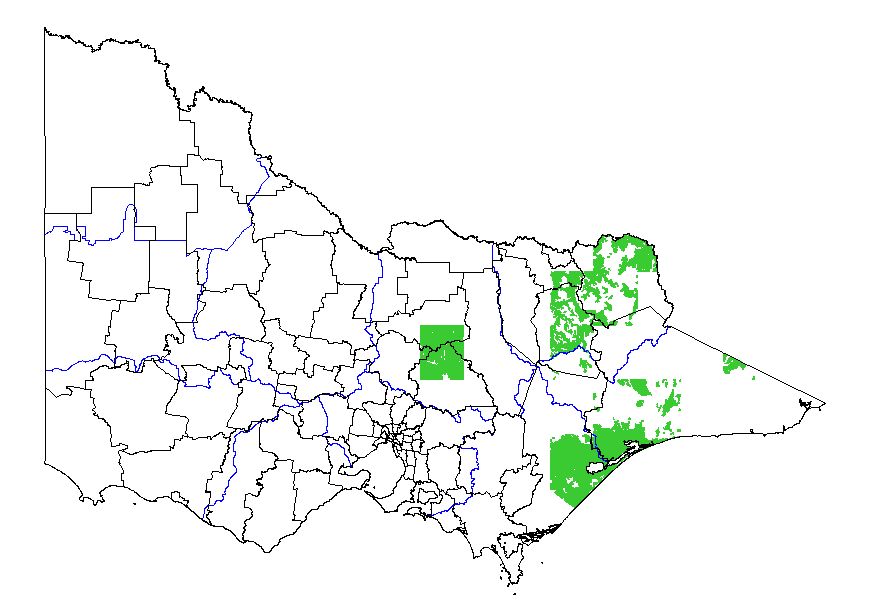

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Broadacre cropping; horticulture; pasture dryland; pasture irrigation Broad vegetation types Coastal scrubs and grassland; coastal grassy woodland; heathy woodland; swamp scrub; inland slopes woodland; sedge rich woodland; montane dry woodland; grassland; plains grassy woodland; valley grassy forest; sub-alpine grassy woodland; montane grassy woodland; riverine grassy woodland; rainshadow woodland Colours indicate possibility of Panicum virgatum infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Individual access likely to be impeded due to the large size of this species growing to a height of 2.1m (Uchytil 1993) and a width of 1m (MGB 2006). | ML | M |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | This weed would not be obvious to the ‘average’ visitor and is unlikely to affect recreation or the aesthetic appeal of the land. This species is grown as an ornamental grass (MBG 2006) and may also be mistaken for an indigenous species. | L | MH |

| 3. Injurious to people? | No information was found to suggest that this species is injurious to people. | L | M |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | This species would have little or negligible affect on aesthetics or structure of site. | L | MH |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | A terrestrial species, no impact on water flow. | L | H |

| 6. Impact water quality? | A terrestrial species, no impact on water quality. | L | H |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | Develops a large, vigorous root system and it is used in erosion control along roadsides, waterways, and on mine tailings (Uchytil 1993; Choi & Wali 1995). Due to its effective growth it was selected from 20,000 species to restore eroded sites in China (Ichizen et al 2005). Likely to decrease the probability of soil erosion. | L | H |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | Due to its significant height to 2.1 m (Uchytil 1993) if it replaced indigenous grasses within vegetation communities it would likely increase the biomass of the community. | L | M |

| 9. Change fire regime? | ‘The standing dead material is apparently a good fuel source, which readily carries fire (Uchytil 1993)’. Switchgrass litter is resistant to matting and provides a good fuel. It needs periodic burning to maintain vigour and abundance (Silzer 2000). Burning significantly increased cover in lowland tall grass prairie sites (Hartnett, Hickman & Walter 1996). Potential to cause moderate change to both frequency and intensity of fire. | MH | M |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC= Floodplain Riparian Woodland (BCS= E); CMA= West Gippsland; Bioreg= Gippsland Plain; CLIMATE potential=L. ‘This plant may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats and may displace desirable vegetation if not managed properly (NRCS 2006)’. The impact that this species would have on vegetation composition is not clear due to a lack of documented information. | M | L |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC= Coastal Headland Scrub (BCS= D); CMA= West Gippsland; Bioreg= Gippsland Plain; CLIMATE potential=L. ‘This plant may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats and may displace desirable vegetation if not managed properly (USDA 2006)’. The impact that this species would have on vegetation composition is not clear due to a lack of documented information. | M | L |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC= Coastal Tussock Grassland (BCS= LC); CMA= West Gippsland; Bioreg= Gippsland Plain; CLIMATE potential=L. ‘This plant may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats and may displace desirable vegetation if not managed properly (USDA 2006)’. The impact that this species would have on vegetation composition is not clear due to a lack of documented information. | M | L |

| 11. Impact on structure? | ‘This plant may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats and may displace desirable vegetation if not managed properly (USDA 2006)’. The impact that this species would have on vegetation community structure is not clear due to a lack of documented information. | M | L |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | ‘This plant may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats and may displace desirable vegetation if not managed properly (USDA 2006)’. Potential to displace native species but no specific information was available on threatened flora species. | MH | L |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | ‘This plant may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats and may displace desirable vegetation if not managed properly (USDA 2006)’. Potential to displace indigenous food sources for fauna but no specific information was found documented. | MH | L |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | ‘This plant may become weedy or invasive in some regions or habitats and may displace desirable vegetation if not managed properly (USDA 2006)’. Potential to displace indigenous food sources for fauna but no specific information was found documented. | M | L |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | In USA provides habitat for nesting, protection from predators and night roosting for a number of birds including ducks, quails, passerines and doves. Ring-necked pheasant nest density and hatch success was highest in switchgrass stands (George et al 1979; Uchytil 1993; USDA 2006). Likely to provide harbour to similar native species. | MH | M |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | Grazing can cause photosensitization in lambs leading to death due to the presence of toxins in the plant (Puoli, Reid & Belesky 1992). There was no information found documented on the affect of these toxins (or other injurious properties) on other animals, and the impact on native fauna is unknown. | M | L |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | ‘…white-tailed deer paw up and eat the rhizomes when winter food is scarce (Uchytil 1993)’. A food source for rabbits (Forest Service 2002). Foliage is palatable and nutritious in early stages of growth but when the seed heads begin to mature palatability and nutrient content decline rapidly (Uchytil 1993). Food source for a serious pest, but foliage only palatable at certain times of the year. | MH | M |

| 18. Provides harbor? | Provides excellent nesting and Autumn/Winter cover for pheasants, quail and rabbits (USDA 2006). Capacity to provide cover and harbour for rabbits. | MH | M |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | In one study, grazing on P. virgatum caused widespread liver lesions leading to secondary photosensitization or ‘hepatotoxicity’ in 17 out of 104 lambs. Symptoms included facial swelling, difficulty breathing, intense itching (pruritus), scabbing around the eyes and a reluctance to move. Some of the lambs recovered when removed from the paddock but 8 died (Puoli, Reid & Belesky 1992). Potential for major decrease (>5%) in yield. | MH | MH |

| 20. Impact quality? | The potential for P. virgatum to cause photosensitization in lambs leading to effects such as facial swelling, difficulty breathing, intense itching (pruritus), scabbing around eyes and a reluctance to move (Puoli, Reid & Belesky 1992) could lead to a decrease in sale price for those animals. Potential to lower produce price by >5%. | MH | M |

| 21. Affect land value? | There is no information to suggest that this species would affect land value. | L | MH |

| 22. Change land use? | The potential to cause photosensitization in lambs (Puoli, Reid & Belesky 1992), may lead to a change in grazing animal species run in paddocks that contain P. virgatum. Minor change to priority of land use. | ML | M |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | A potential increase in veterinary expenses to treat lambs affected by photosensitization, as a result of consuming P. virgatum (Puoli, Reid & Belesky 1992), may lead to an overall minor increase in production costs. | M | M |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Barley yellow dwarf virus is present in natural populations of P. virgatum (Garret et al 2004) This is an important disease of cereals including barley and wheat in Victoria (Hollaway & Bedggood 2003). Host to major disease of important agricultural produce. | H | MH |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | Seeds are shed in Autumn or Winter and require Winter dormancy before they germinate in the Spring. Germination begins when soil temperatures reach 20 o C (Uchytil 1993). Requires natural seasonal disturbances for germination. | MH | MH |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | ‘…somewhat shade tolerant…’ (Uchytil 1993). Will grow in part shade (MGB 2006). Inhabits open oak and pine woodlands (Freckman & Lelong 2005). Can establish under moderate canopy cover. | MH | MH |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Grows in tallgrass prairies, fresh and brackish marshes, open oak/pine woodlands and along riverbanks (USU 2005; Uchytil 1993). Able to establish in minor disturbed ecosystems eg wetlands, riparian, grasslands, open woodlands. | MH | MH |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Warm-season perennial grass to 2.1m (Uchytil 1993). Lifeform: Grass | MH | MH |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | Not allelopathic (NRCS 2006). ‘Andropogon scoparius and Panicum virgatum were shown to be allelopathic. In disturbed prairies, weedy spp. became established but in undamaged intact stands they were inhibited’ (Still 1978). A medium rating has been assigned due to conflicting information on the presence of allelopathic properties in this species. | M | L |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | P. virgatum decreases in response to cattle and bison grazing (Hartnett, Hickman & Walter 1996; Silzer 2000) but recovers when stocking rates are reduced (Gillen et al 1998). Grazed paddocks need to be rested 30-60 days before being grazed again (NRCS 2006). Consumed and recovers slowly. | ML | MH |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Rapid growth rate (USDA 2006). Vegetative growth is rapid after initial Spring flush. Regrowth resumes in April, and by early June foliage often exceeds 46 cm in height (Uchytil 1993). Three months after germination plants may be up to 50cm tall (Uchytil 1993). Establishes faster than most warm season grasses (Undersander 2001). Rapid growth rate. | H | M |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Grows on medium wet to wet soils (MGB 2006) and tolerant of Spring flooding (Uchytil 1993). Moderately tolerant of soil salinity (Uchytil 1993). Unharmed by burning, as rhizomes are resistant to the heat of the fire (Silzer 2000). Very tolerant of poor soils, flooding and drought (Bransby 2005). A drought resistant grass (Cameron 1954). Highly tolerant of drought and fire and moderately tolerant of salinity and waterlogging. | MH | M |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | Reproduces both sexually and vegetatively via rhizomes (Uchytil 1993). | H | MH |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | Calderon, Alan & Barrantes (2000) found the average number of spikelets on an inflorescence to be 1185. With one fertile floret per spikelet (Clayton, Harman & Williamson 2006), 1185 seeds per inflorescence could potentially be produced. Images of P. virgatum indicate that many inflorescences are produced on a single plant. Above 2000 seeds likely to be produced by a single plant. | H | MH |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | ‘Seeds of Panicum virgatum would stay viable for a longer period of about 5 years’ (Zhang & Maun 1994). Seeds viable for approximately 5 years. | L | H |

| 12. Reproductive period? | Long lifespan (NRCS 2006). No specific information was found documented on the lifespan of this species. | M | L |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | Plants flower in the first or second year (Floridata 2003). Produces propagules 1-2 years after germination. | MH | M |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | ‘Early hunters avoided patches of this grass when cutting buffalo meat because the tiny spikes would get embedded in the meat. These sharp spikes also have an annoying inclination to creep inside one’s pants leg’ (Floridata 2003). Utilised for habitat by a number of mammal and bird species (Uchytil 1993). ‘Lemma apex acute’ (Clayton, Harman & Williamson 2006). Likely that seeds would be transported externally by animals (or humans) through attachment of the sharply pointed lemma in fur or feathers. | MH | M |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | Due to large seed production capabilities (Clayton, Harman & Williamson 2006) and attachment properties of the seed (Floridata 2003) it is very likely that at least one seed would disperse greater than one kilometre. | H | M |

References

Bransby B (Auburn University) 2005, Switchgrass Profile: Bioenergy Feedstock Information Network, U.S. Department of Energy-Biomass Program, Washington, USA, viewed: 28 November 2006, http://bioenergy.ornl.gov/papers/misc/switchgrass-profile.html

Calderon J, Alan E & Barrantes, U 2000, ‘Structure size and production of weed seeds in the humid tropic’, Agronomia Mesoamericana, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 31-39.

Cameron DG 1954, ‘New grasses for soil conservation in New South Wales’, Journal of Soil Conservation, N.S.W, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 116- 126.

Choi YD & Wali MK 1995, ‘The role of Panicum virgatum (Switch Grass) in the Revegetation of Iron-Mine Tailings in Northern New York’, Restoration Ecology, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 123-132.

Clayton, W.D., Harman, K.T. and Williamson, H. (2002 onwards). World Grass Species: Descriptions, Identification, and Information Retrieval, viewed: 18 December 2006, http://www.kew.org/data/grasses–db.html

Denver Plants 2006, Denver Plants, Denver, Colorado, USA, viewed: 21 December 2006, http://www.denverplants.com/hialt/herbaceous.htm

Floridata 2001, Floridata: Panicum virgatum, Floridata.com LC, Tallahassee, Florida, USA, viewed: 19 December 2006, http://www.floridata.com/ref/p/pani_vir.cfm

Forest Service 2002, Illinois Plant Information Network- Panicum virgatum, United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service, North East Research Station, Delaware, viewed: 18 December 2006, http://www.fs.fed.us/ne/delaware/ilpin/2076.co

Freckman RW & Lelong, MG 2005, Panicum virgatum: In ‘Flora of North America’, Intermountain Herbarium, Utah State University, viewed: 20 November 2006, http://herbarium.usu.edu/treatments/Panicum.htm#Panicum_virgatum

Garrett KA, Dendy SP, Power AG, Blaisdell GK, Alexander HM & McCarron JK 2004, ‘Barley yellow dwarf disease in natural populations of dominant tallgrass prairie species in Kansas’, Plant Disease. American Phytopathological Society (APS Press) St. Paul, USA, vol. 88, no. 5, pp. 574.

George RR, Farris AL, Schwartz CC, Humburg DD & Coffey JC 1979, ‘Native prairie grass pastures as nest cover for upland birds’, Wildlife Society Bulletin, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 4-9.

Gillen RL, McCollum FT, Kenneth WT & Hodges ME 1998, ‘Tallgrass prairie response to grazing system and stocking rate’, Journal of Range Management, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 139-146.

Hafliger E & Scholz H 1980, Grass Weeds 1, CIBA-GEIGY Ltd., Basle, Switzerland.

Hartnett DC, Hickman KR & Fischer Walter LE 1996, ‘ Effects of bison grazing, fire, and topography on floristic diversity in tallgrass prairie’, Journal of Range Management, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 413-420.

Holloway G & Bedggood W 2003, ‘Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus (BYDV)’, Information Notes: Department of Primary Industries, Victorian Government, viewed: 20 December 2006, http://www.dpi.vic.gov.au/dpi/nreninf.nsf

Ichizen N, Takahashi H, Nishio T, Liu G, Li D & Huang J 2005, ‘Impacts of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) planting on soil erosion in the hills of the Loess Plateau in China’, Weed Biology & Management, vol. 5, pp. 31-34.

Missouri Botanical Garden (MBG) 2005, Panicum virgatum, Kemper Centre for Home gardening, Missouri Botanical Gardens, viewed 21 June 2006, http://www.mobot.org/gardeninghelp/plantfinder/Plant.asp?code=L460

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) 2006, Plant Fact Sheet: Switchgrass, Panicum virgatum, Natural Resources Conservation Service, USDA, viewed: December 2006, http://plants.usda.gov/factsheet/pdf/fs_pavi2.pdf

Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) 2006, Conservation Plant Characteristics for: Panicum virgatum, NRCS, United States Department of Agriculture, viewed: 20 November 2006, http://plants.nrcs.usda.gov/cgi_bin/topics.cgi?earl=plant_attribute.cgi&symbol=PAVI2

Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Centre (OARDC), Cocoa Integrated Pest Management, OARDC, Ohio State University, viewed: 18 December 2006, http://www.oardc.ohio-state.edu/cocoa/main_wds.htm

Parrish, DJ & Fike, JH 2005, ‘The Biology & Agronomy of Switchgrass for Biofuels’, Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, vol. 24, pp 423-459.

Puoli JR, Reid RL & Belesky DP 1992, ‘Photosensitization in lambs grazing switchgrass’, Agronomy Journal, vol. 84, pp. 1077-1080.

Randall R 2004, Pers. comm. in ‘Weeds CRC: Enviroweeds Archive Titles - Panicum virgatum’, CRC for Australian Weed Management, University of Adelaide, South Australia, viewed: 12 December 2006, http://www.weeds.crc.org.au/cropweeds/crop_weeds_p.html#switch

Silzer T 2000, Panicum virgatum L. (fact sheet), Department of Plant Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, Canada, viewed: 20 November 2006, http://www.usask.ca/agriculture/plantsci/classes/range/panicum.html

Still KR 1978, ‘Allelopathic inhibition of weed invasion by Andropogon scoparius Michx. In climax prairies’, Dissertion Abstracts International, vol. 38, no. 9, pp. 4047.

Uchytil RJ 1993, Panicum virgatum, Fire Effects Information System, USDA Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture, viewed: 20 November 2006, http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/graminoid/panvir/all.html

Undersander D 2001, UW Extension: Establishment and Management of Switchgrass, Cooperative Extension, University of Wisconsin, viewed: 20 November 2005, http://www.uwex.edu/ces/forage/pubs/switchgrass.htm

Zhang J & Maun MA 1994, ‘Potential for seed bank formation in seven Great Lakes sand dune species’, American Journal of Botany, vol. 81, no. 4, pp. 387-394.

Global present distribution data references

Dore WG & McNeil J (Agriculture Canada) 1980, Grasses of Ontario, Canadian Government Publishing Centre, Supply & Services Canada, Hull, Quebec, Canada.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2006, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed 19 December 2006, http://www.gbif.org/

Gillen RL, McCollum FT, Kenneth WT & Hodges ME 1998, ‘Tallgrass prairie response to grazing system and stocking rate’, Journal of Range Management, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 139-146.

Hartnett DC, Hickman KR & Fischer Walter LE 1996, ‘ Effects of bison grazing, fire, and topography on floristic diversity in tallgrass prairie’, Journal of Range Management, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 413-420.

Ichizen N, Takahashi H, Nishio T, Liu G, Li D & Huang J 2005, ‘Impacts of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.) planting on soil erosion in the hills of the Loess Plateau in China’, Weed Biology & Management, vol. 5, pp. 31-34.

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.