Asparagus fern (Asparagus africanus)

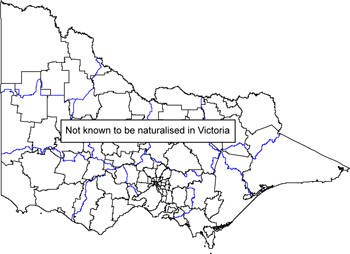

Present distribution

|  This weed is not known to be naturalised in Victoria | ||||

| Habitat: Occurs in shrub habitat, successional habitat (Tekle 2001), remnant, semi-evergreen, vine thicket and brigalow forest communities, wetter eucalypt communities and moist gullies (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006), rainforest, adjacent roadside areas (Weeds Australia 2007), adjacent to mangroves (Gang, Agatsiva 1992). Also occurs in Cupressus lusitanica and Eucalyptus globulus plantations in Ethiopia (Michelsen et al. 1993). Clay tolerant (New Plant 2007). Drought, frost, waterlogging, and salinity tolerant (Weeds Australia 2007; New Plant 2007). | |||||

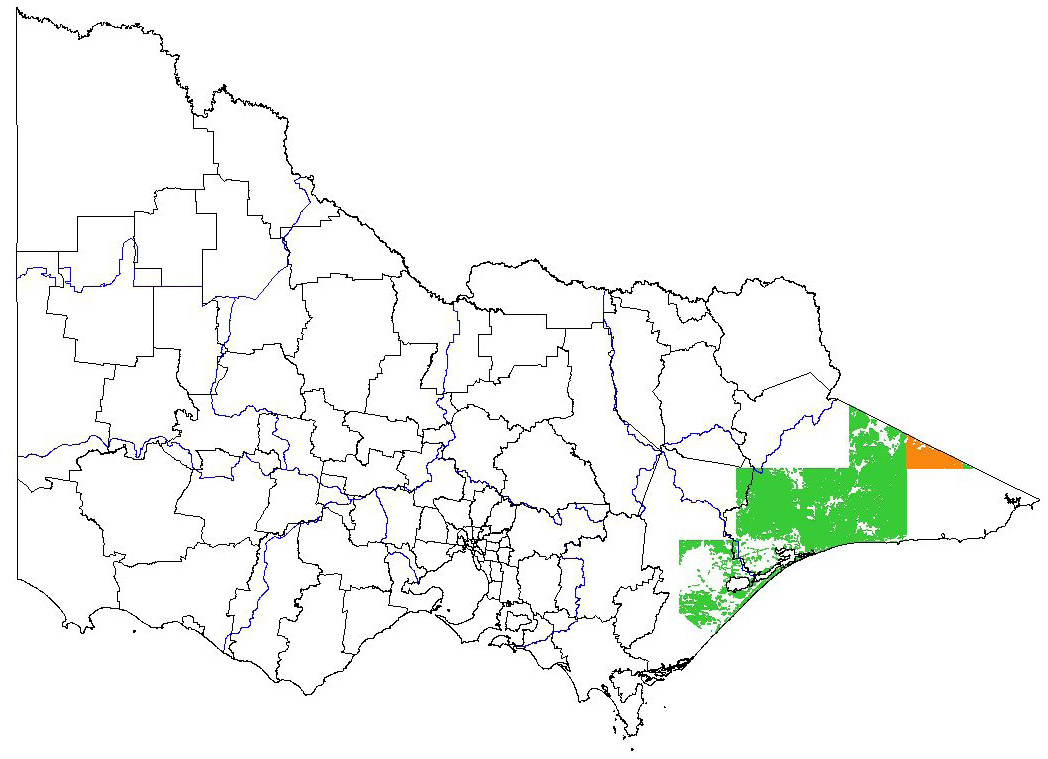

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Forestry Ecological Vegetation Divisions Coastal; swampy scrub; freshwater wetland (permanent); treed swampy wetland; lowland forest; foothills forest; forby forest; damp forest; riparian; wet forest; rainforest; high altitude shrubland/woodland; high altitude wetland; alpine treeless; alluvial plains woodland; ironbark/box; riverine woodland/forest; freshwater wetland (ephemeral); saline wetland Colours indicate possibility of Asparagus africanus infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | “Climbing habit with stems up to approximately ten metres long that smother native scrub and trees” (Armstrong et al. 2006) – high nuisance value | mh | h |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | “Climbing habit with stems up to approximately ten metres long that smother native scrub and trees” (Armstrong et al. 2006) – some recreational uses affected | mh | h |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Thorny shrub (Debella et al. 1999) – spines, burrs or toxic properties at most times of the year | mh | h |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | “Climbing habit with stems up to approximately ten metres long that smother native scrub and trees” (Armstrong et al. 2006) Although not known to be a problem for buildings, may smother heritage gardens or outdoor sites of cultural significance – moderate visual effect | ml | m |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Terrestrial (Armstrong et al. 2006) – little or negligible affect on water flow | l | h |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Terrestrial (Armstrong et al. 2006) – no noticeable effect on dissolved oxygen or light levels | l | h |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | “Roots are fibrous and form dense mats just below the soil surface” (Weeds Australia 2007) – low probability of large scale soil movements | l | m |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | “Grows prolifically in remnant, semi-evergreen, vine thicket and brigalow forest communities, wetter eucalypt communities and moist gullies. It frequently climbs and covers native vegetation, reducing tree health and forming a dense ground cover that suppresses recruitment of native species.” (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006) – biomass significantly decreased | h | h |

| 9. Change fire regime? | “Grows prolifically in remnant, semi-evergreen, vine thicket and brigalow forest communities, wetter eucalypt communities and moist gullies. It frequently climbs and covers native vegetation, reducing tree health and forming a dense ground cover that suppresses recruitment of native species.” (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006). Also found in rainforest (Weeds Australia 2007) – although it may prevent the regeneration of taller native species, it generally grows in wet areas where fire would not usually occur – minor change to either frequency of intensity of fire risk | ml | mh |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC = Montane Riparian Woodland (V); CMA = East Gippsland; Bioregion = Highlands – Far East; M CLIMATE potential. “Grows prolifically in remnant, semi-evergreen, vine thicket and brigalow forest communities, wetter eucalypt communities and moist gullies. It frequently climbs and covers native vegetation, reducing tree health and forming a dense ground cover that suppresses recruitment of native species.” (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006). “Massive climbing asparagus infestations threaten the remnant patch [of Brigalow scrub], which includes other native species such as currant bush (Carissa ovata R. Br.), Spartothamnella juncea (A. Cunn. ex Walp.) Briq., Parsonia lanceolata R. Br., wombat berry (Eustrephus latifolius R. Br. ex Ker Gawl.) and Acalypha capillipes Mull. Arg.” (Armstrong et al. 2006). “Can often completely cover smaller trees, understorey shrubs and ground layer plants. Roots are fibrous and form dense mats just below the soil surface, which presumably interferes with the establishment and survival of seedlings of native species” (Weeds Australia 2007) Minor displacement of some dominant or indicator spp. within any one strata/layer | ml | h |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC = Cool Temperate Rainforest (R); CMA = East Gippsland; Bioregion = Highlands – Far East; M CLIMATE potential. “Grows prolifically in remnant, semi-evergreen, vine thicket and brigalow forest communities, wetter eucalypt communities and moist gullies. It frequently climbs and covers native vegetation, reducing tree health and forming a dense ground cover that suppresses recruitment of native species.” (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006). “Massive climbing asparagus infestations threaten the remnant patch [of Brigalow scrub], which includes other native species such as currant bush (Carissa ovata R. Br.), Spartothamnella juncea (A. Cunn. ex Walp.) Briq., Parsonia lanceolata R. Br., wombat berry (Eustrephus latifolius R. Br. ex Ker Gawl.) and Acalypha capillipes Mull. Arg.” (Armstrong et al. 2006). “Can often completely cover smaller trees, understorey shrubs and ground layer plants. Roots are fibrous and form dense mats just below the soil surface, which presumably interferes with the establishment and survival of seedlings of native species” (Weeds Australia 2007). Minor displacement of some dominant or indicator spp. within any one strata/layer | ml | h |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC = Wet Forest (LC); CMA = East Gippsland; Bioregion = Highlands – Far East; M CLIMATE potential. “Grows prolifically in remnant, semi-evergreen, vine thicket and brigalow forest communities, wetter eucalypt communities and moist gullies. It frequently climbs and covers native vegetation, reducing tree health and forming a dense ground cover that suppresses recruitment of native species.” (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006). “Massive climbing asparagus infestations threaten the remnant patch [of Brigalow scrub], which includes other native species such as currant bush (Carissa ovata R. Br.), Spartothamnella juncea (A. Cunn. ex Walp.) Briq., Parsonia lanceolata R. Br., wombat berry (Eustrephus latifolius R. Br. ex Ker Gawl.) and Acalypha capillipes Mull. Arg.” (Armstrong et al. 2006). “Can often completely cover smaller trees, understorey shrubs and ground layer plants. Roots are fibrous and form dense mats just below the soil surface, which presumably interferes with the establishment and survival of seedlings of native species” (Weeds Australia 2007) Minor displacement of some dominant or indicator spp. within any one strata/layer | ml | h |

| 11. Impact on structure? | “Grows prolifically in remnant, semi-evergreen, vine thicket and brigalow forest communities, wetter eucalypt communities and moist gullies. It frequently climbs and covers native vegetation, reducing tree health and forming a dense ground cover that suppresses recruitment of native species.” (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006). “Massive climbing asparagus infestations threaten the remnant patch [of Brigalow scrub], which includes other native species such as currant bush (Carissa ovata R. Br.), Spartothamnella juncea (A. Cunn. ex Walp.) Briq., Parsonia lanceolata R. Br., wombat berry (Eustrephus latifolius R. Br. ex Ker Gawl.) and Acalypha capillipes Mull. Arg.” (Armstrong et al. 2006). “Can often completely cover smaller trees, understorey shrubs and ground layer plants. Roots are fibrous and form dense mats just below the soil surface, which presumably interferes with the establishment and survival of seedlings of native species” (Weeds Australia 2007) – major effect on all layers | h | h |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | “Massive climbing asparagus infestations threaten the remnant patch [of Brigalow scrub], which includes other native species such as currant bush (Carissa ovata R. Br.), Spartothamnella juncea (A. Cunn. ex Walp.) Briq., Parsonia lanceolata R. Br., wombat berry (Eustrephus latifolius R. Br. ex Ker Gawl.) and Acalypha capillipes Mull. Arg.” (Armstrong et al. 2006). However it is not yet know to affect Bioregional Priority 1A or VROT spp in Victoria | mh | l |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | “Massive climbing asparagus infestations threaten the remnant patch [of Brigalow scrub], which includes other native species such as currant bush (Carissa ovata R. Br.), Spartothamnella juncea (A. Cunn. ex Walp.) Briq., Parsonia lanceolata R. Br., wombat berry (Eustrephus latifolius R. Br. ex Ker Gawl.) and Acalypha capillipes Mull. Arg.” (Armstrong et al. 2006) and is therefore likely to change habitat. However it is not yet know to affect Bioregional Priority or VROT spp in Victoria | mh | l |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | “Grows prolifically in remnant, semi-evergreen, vine thicket and brigalow forest communities, wetter eucalypt communities and moist gullies. It frequently climbs and covers native vegetation, reducing tree health and forming a dense ground cover that suppresses recruitment of native species.” (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006). Also found in rainforest (Weeds Australia 2007) – habitat changed dramatically, leading to possible extinction of non-threatened fauna | h | m |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | It has been shown to occur more frequently in grazing excluded plots (Lenzi-Grillini et al. 1996) and seeds are dispersed by native birds (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006).– may provide a food source for herbivores and frugivores – provides some assistance in either food or shelter to desirable species | mh | h |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | Thorny shrub (Debella et al. 1999) – spines, burrs or toxic properties to fauna at certain times of the year | mh | h |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | It has been shown to occur more frequently in grazing excluded plots (Lenzi-Grillini et al. 1996) and seeds are dispersed by native birds (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006).– may provide a food source for herbivores and frugivores, such as rabbits and invasive birds – supplies food to a serious pest, but at low levels | mh | m |

| 18. Provides harbor? | It frequently climbs and covers native vegetation (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006) – capacity to provide harbour and permanent warrens for foxes and rabbits throughout the year | h | h |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | Listed as an agricultural weed (Randall 2007) and found to occur in Cupressus lusitanica and Eucalyptus globulus plantations in Ethiopia (Michelsen et al. 1993) – however to what extent is unknown | m | l |

| 20. Impact quality? | Listed as an agricultural weed (Randall 2007) and found to occur in Cupressus lusitanica and Eucalyptus globulus plantations in Ethiopia (Michelsen et al. 1993) – however to what extent is unknown | m | l |

| 21. Affect land value? | Listed as an agricultural weed (Randall 2007) and found to occur in Cupressus lusitanica and Eucalyptus globulus plantations in Ethiopia (Michelsen et al. 1993) – however to what extent is unknown | m | l |

| 22. Change land use? | Mechanical removal is most effective, however is very time consuming and “impractical for large-scale infestations.” Chemicals may be used (Armstrong et al. 2006) however this presents problems for organic farmers, although the scale of damage on an agricultural level is unknown | m | l |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | Listed as an agricultural weed (Randall 2007) and found to occur in Cupressus lusitanica and Eucalyptus globulus plantations in Ethiopia (Michelsen et al. 1993) – however to what extent is unknown | m | l |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Plants in the genus Asparagus are known to host asparagus beetle (Crioceris asparagi), spotted asparagus beetle (Criocerus duodecimpunctata), asparagus fern caterpillar (Spodoptera exigua) – also known as beet armyworm, asparagus fly (Platyparaea poeciloptera) – a fruit fly, fusarium root and crown rot (Fusarium monoliforme and Fusarium oxysporium asparagi), asparagus rust (Puccinia asparagi), botrytis blight (Botrytis cinerea), and some Lepidoptera species (Coleophora lineapulvella, ghost moth, the nutmeg, small fan-footed wave, and turnip moth) (Absolute Astronomy 2009) – host to major and severe disease or pest of important agricultural produce | h | ml |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | Germinates in Australia from February to April (Weeds Australia 2007) – requires natural seasonal disturbances | mh | m |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | Mechanisms may be in place to prevent germination in open sun conditions (Kos, Poschold 2007) – requires mores specific requirements to establish | ml | h |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Was found to occur, not in degraded habitat (“areas where trees and shrubs had largely disappeared by 1991”), but in shrub habitat (“areas with many shrubs and few scattered small trees”) and in successional habitat (“areas where substantial secondary succession towards forest had taken place”) (Tekle 2001). “Grows prolifically in remnant, semi-evergreen, vine thicket and brigalow forest communities, wetter eucalypt communities and moist gullies. It frequently climbs and covers native vegetation, reducing tree health and forming a dense ground cover that suppresses recruitment of native species.” (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006). Also found in rainforest (Weeds Australia 2007) – establishes in healthy and undisturbed natural ecosystems | h | mh |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Climbing habit (Armstrong et al. 2006). | ml | h |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | Although A. africanus is not known to be allelopathic, Asparagus officinalis was found to “reduce the growth of tomato and barnyardgrass by as much as 80% as compared with peat moss-amended controls.” (Rice 1984) A. africanus may have allelopathic potential, however this is unknown | m | l |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Density and frequency of A. africanus were higher in enclosures (i.e. the exclusion of large herbivores) than outside. On one site there were no plants of A. africanus outside the enclosure (Mengistu et al. 2005). In another study, it occurred more frequently in grazing excluded plots (Lenzi-Grillini et al. 1996) – consumed but recovers slowly. Reproduction strongly inhibited by herbivory but still capable of vegetative propagule production; weed may still persist | ml | h |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | “It frequently climbs and covers native vegetation.” (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006) – rapid growth rate that will exceed most other species of the same life form | h | h |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | “plants may dieback during the hot summer months from December through to mid February, however the sub-surface rhizomes will ensure the plant’ survival.” (Weeds Australia 2007) – Drought tolerant. Frost resistant (New Plant 2007). “Present in many moist gullies.” (Weeds Australia 2007) – Tolerant to waterlogging. Found growing in close proximity to mangroves (Gang, Agatsiva 1992) – tolerant to waterlogging and salinity. Tolerant to frost, drought, waterlogging and salinity. | h | m |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | Sexual and vegetative (Batianoff, Butler 2006) | h | h |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | “seeds are viable while the fruit is immature and each mature plant produces an estimated 21,000 seeds” (Armstrong et al. 2006) | h | h |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | “Seeds/ propagules are viable for 1-2yrs” (Kedron Brook Catchment Branch 2007) | ml | m |

| 12. Reproductive period? | Perennial (Debella et al. 1999) – mature plant produces viable propagules for 3-10 years | mh | m |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | “Vegetation regeneration occurs in winter” and “in cultivation, climbing asparagus plants flower 36 months after germination” (Weeds Australia 2007) – reaches maturity and vegetative propagules become separate individuals in under a year | h | m |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Spread by dumping of garden waste and seed dispersal by native birds (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006). Seeds are “dispersed by birds such as Silver-eye” (Armstrong et al. 2006) | h | h |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | Spread by dumping of garden waste and seed dispersal by native birds (Vivian-Smith et al. 2006). Seeds are “dispersed by birds such as Silver-eye” (Armstrong et al. 2006) – very likely that at least one propagule will disperse greater than one kilometre | h | h |

References

Absolute Astronomy (2009) Asparagus (genus). Available at http://www.absoluteastronomy.com/topics/Asparagus_(genus) (verified 6 May 2009).

Armstrong TR, Breaden RC, Hinchcliffe D (2006) The control of climbing asparagus (Asparagus africanus Lam.) in remnant Brigalow scrub in south-east Queensland. Plant Protection Quarterly 21(3), 134-136.

Batianoff GN, Butler DW (2006) Impact assessment and analysis of sixty-six priority invasive weeds in south-east Queensland. Plant Protection Quarterly 18(1), 11-17.

Debella A, Haslinger E, Kunert O, Michl G, Abebe D (1999) Steroidal saponins from Asparagus africanus. Phytochemistry 51, 1069-1075.

Gang PO, Agatsiva JL (1992) The current status of mangroves along the Kenyan coast: a case study of Mida Creek mangroves based on remote sensing. Hydrobiologia 247, 29-36.

Kendron Brook Catchment Branch (2007) Kedron Brook Catchment remnant vegetation prioritising and weed mapping project. Prepared by Kedron Brook Catchment Branch,

WPSQ and City Policy & Strategy, Water Resources, Brisbane City Council. Available at http://www.kedronbrook.org.au/projects_funding/Weed_Report_290108/20080129_final_report.pdf (verified 29 April 2009).

Kos M, Poschlod P (2007) Seeds use temperature cues to ensure germination under nurse-plant shade in Xeric Kalahari Savannah. Annals of Botany 99, 667-675.

Lenzi-Grillini CR, Viskanic P, Mapesa M (1996) Effects of 20 years of grazing exclusion in an area of the Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda. African Journal of Ecology 34, 333-341.

Mengistu T, Teketay D, Hulten H, Yemshaw Y (2005) The role of enclosures in the recovery of woody vegetation in degraded dryland hillsides of central and northern Ethiopia.

Journal of Arid Environments 60, 259-281.

New Plant (2007) Catalogue 2007; new plants for your indigenous palette. New Plant Nursery. Available at http://www.newplant.co.za/plants/NewPlantCatalogue2007.pdf (verified 15 April 2009).

Peters CR, O’Brien EM, Box EO (1984) Plant types and seasonality of wild-plant foods, Tanzania to Southwestern Africa: Resources for models of the natural environment. Journal of Human Evolution 13, 397-414.

Randall R (2007) Asparagus africanus. Global Compendium of Weeds. Available at http://www.hear.org/gcw/species/asparagus_africanus/ (verified 6 May 2009).

Rice EL (1984) Allelopathy, Second edition. Academic Press, Orlando, Florida.

Tekle K (2001) Natural regeneration of degraded hillslopes in Southern Wello, Ethiopia: a study based on permanent plots. Applied geography 21, 275-300.

Vivian-Smith G, Gosper CR, Grimshaw T, Armstrong T (2006) Ecology and management of subtropical invasive asparagus (Asparagus africanus Lam. and A. aethiopicus L.). Plant Protection Quarterly 21(3), 98.

Weeds Australia (2007) Climbing asparagus. Available at http://www.weeds.org.au/WoNS/bridalcreeper/docs/Asparagus_Weeds_BPMM-6.pdf (verified 15 April 2009).

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) (2009) Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, Available at

http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/ (verified 15 April 2009).

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) (2009) Global biodiversity information facility, Available at http://www.gbif.org/ (verified 15 April 2009).

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.