Land Management on Farms in Southern Gippsland and Westernport

Fertiliser Management | Effluent Management | Pasture Management | Winter Grazing | Cultivation | Erosion Control | Farm Access | Riparian Zones | Drainage | Whole Farm Planning | Biodiversity on Farms | Feedpads | Trees on Farms | Wet Areas on Farms

| The information in this section is aimed at providing some tips that relate to land and water management in this region. Each farming system is different and a management strategy that may be practical and economical on one farm may be unsuitable for another. The knowledge of a landholder/manager will enable the most suitable management ideas to be implemented. Land managers should look at all options or strategies to see what is best for their farm. This information has been developed from the following projects: |  |

Better Management of Surface Water in Intensive Grazing

This (formerly) NRE/NHT project was completed in 2002. It focused on demonstration sites in the Bass and Lang Lang River catchments (i.e. at Nyora, Loch, Drouin South and Lang Lang). On these sites, various combinations of grassed waterways, fencing, re-vegetated drainage lines, sediment raps, wetlands, water storages and track access improvements were utilised. All sites focused on providing benefits to the landholder in terms of productivity and/or farm improvements, as well as environmental benefits - and were regularly monitored by landholders for water quality. The project also focused on the many practices which reduce the speed and improve the quality of run-off whilst providing the landholder with additional benefits such as increased production. The project was managed by Janine Price (formaly of DPI).

Sustainable Strzelecki Agriculture

Sustainable Strzelecki Agriculture (SSA) was an Upper Westernport Catchment Sustainable Management Project. The Upper Westernport Catchment Sustainable Management Project was supported by the Victorian Government through the Second Generation Landcare Grants Program. The SSA project covered the Poowong, Mt Lyall, Triholm, Loch, Nyora and surrounding communities in the Strzelecki & Westernport region. Sustainable Strzelecki Agriculture had many different projects underway - covering issues related to control of effluent runoff, farm tracks, erosion, waterlogged paddocks, management of land use for pea crops, improvement of barren paddocks, loss of nutrients, effluent re-use and management of pasture using different fertiliser types. The SSA project was managed by Natalya Stivic.

Information developed from these projects was also used in the development of Land Management Calendars which presented a focus topic each month. Information used to develop these calendars has also been used to develop content in this section of the website. The 2003 Calendar was produced by Landcare's Sustainable Strzelecki Agriculture (SSA) project in association with the Port Phillip and Westernport Catchment Management Authority.

Fertiliser Management

|  |

|

|

Photographs by: Rawdon Sthradher (Fine Focus Photography).

Effluent Management

Dairy Effluent

A 100 cow herd each year produces effluent equivalent to that of a township of 1 000 people. The Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) is 10 times greater and can do extreme damage to local waterways. By law, ensure that all dairy effluent remains on the farm and does not leave the farm boundary.

- Dairy shed effluent can be a valuable fertiliser and soil conditioner. It is estimated that during one lactation a 100 cow herd deposits 80 kg Phosphorus (910 kg single super), 250 kg Nitrogen (540 kg Urea) and 270 kg Potassium (540 kg Potash) in the yards.

- Approximately 8-10% of the daily effluent is deposited in the yard. A general rule of thumb to minimise nutrient overload, and soil structure and pasture damage, is to apply effluent to 4 ha for every 100 cows milked. If possible, rotate your effluent around different areas of the farm each year and spread over as large an area as possible/accessible.

- Applying dairy effluent on pastures and crops can boost pasture growth by utilising the nutrients, organic matter and water in the effluent. However, the levels of nutrient in a storage pond are less than fresh dung and urine. Have your ponds tested to work out the levels and rates of application.

- Do not graze areas where effluent has been applied for at least 2 weeks in the summer and at least 3 weeks in winter if daily application must occur.

- Apply effluent just after grazing when the pastures are low and weather is hot/dry. This ensures sunlight (UV radiation) and wind can penetrate to the soil surface to kill microbes.

- Applying effluent just after grazing also means pastures will not need to be grazed until the next rotation (several weeks) - ensuring animal health considerations are addressed.

- Do not allow young stock (under 12 months) to graze or have access to treated areas. Do not allow drains from treated areas to flow into areas with young stock. This is to help reduce the risk of infections especially from Johnes, as young stock have not yet built up immunity to cope with such diseases.

- Consider applying effluent to the lower fertility paddocks, in order to boost organic matter and nutrients.

- Consider recycling your effluent for yard wash-down to minimise the amount of freshwater entering the system.

- Crusting of effluent ponds is generally an indication that the pond is overloaded and too small for your system. The bacteria can not keep up with the effluent coming in and can not breakdown the sludge. Your local effluent officer can work out the size of the system you require.

Pasture Management

|  |

- Preferably graze south-facing slopes in summer as they are more protected from the elements (sun and drying winds) and have a better pasture cover. Graze north-facing slopes in winter as they are warmer, soils dry quicker, and they have better grass growth.

- Steep slopes are often difficult to access - control weeds and vermin and manage pasture. They may also be susceptible to erosion. Decide whether it is practical to include these areas in a normal grazing rotation - use them for lighter grazing, non-milking stock or perhaps for revegetation.

- When establishing pastures, light frequent grazing is necessary to stop grasses from smothering clovers, to keep weeds in check and to encourage the pasture to form a dense ground cover. Grazing can start once seedlings are able to resist being pulled out (preferably graze at 12-15 cm down to 5 cm) by the grazing animals (light-footed stock preferred) and the soil is firm enough to support them.

Aim to maintain good pasture cover for feed and soil protection. Photographs by: Rawdon Sthradher (Fine Focus Photography). | Other considerations

|

Winter Grazing

|  |

- Rectangular paddocks will aid in making strip grazing, mowing and moving cattle easier. If grazing strips are more squarish rather than rectangular, there will be less treading damage during wet periods. In long, narrow strips cows tend to walk up and down more looking for feed.

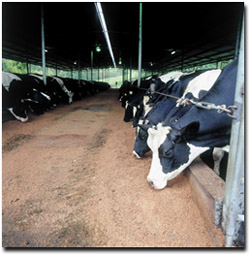

A feedpad used for on-off grazing. Photographs by: Rawdon Sthradher (Fine Focus Photography). |

|

|  |

Snow peas on a steep slope near the Bass River. Steep slope and up and down cultivation increases the likelihood of soil and nutrient loss. Photos by: Rawdon Sthradher (Fine Focus Photography). |

|

Erosion Control

|  |

- Planting out an eroded area may result in the small loss of land (usually unproductive anyway if eroding) in the short term but will save a larger area for the future. Eroding land takes with it valuable topsoil and nutrients. Pasture around the area may improve with the tree planting and be more productive than the land lost.

- If undertaking erosion control and revegetation works, fence the area to protect the gully from stock until restoration is complete. Lightly graze for the first 2-3 years to allow the pasture to develop and produce a strong root system which will bind the soil together and maximise water use.

A tunnel erosion site that has been fenced and re-vegetated. Photographs by: Rawdon Sthradher (Fine Focus Photography). |

|

Farm Access

Laneways should not be raceways. Straight laneways promote ease of cow flow and are attractive as well as being easy to fence, construct and maintain. Despite this, the lay of the land will be the determinant in laneway configuration. Geometrically shaped layouts that avoid sharp corners, steep gradients, cuts and fills and drainage courses are preferred

Construct laneways with an outsloping surface to encourage dispersed discharge of run-off rather than concentrating it in table drains for discharge at one site.

If table drains are present, runoff from tracks should be diverted at regular intervals onto stable undisturbed grassed areas to trap sediment and encourage infiltration of water.

A well-constructed laneway needs to have a well-formed foundation. Research the surface material that best suits the farm terrain and soil type.

Surface material must form an impervious barrier to water and not be harmful to cows hooves. Avoid large stones as they get kicked out of the track and leave the surface susceptible to water and more damage (they can also damage hooves).

Laneway access is recommended to all paddocks, otherwise grass is both wasted and damaged as cows walk across it to get to another paddock.

Autumn is the best time for laneway maintenance. It is recommended that the surface of the tracks be scraped to remove loose material and manure to promote drainage. Any depressions or rills should be filled, and if necessary, the pavement should be repaired by placement of suitable material over areas of fill.

Currently gates of approximately 4 meters are commonly used. This width, however, is too small for most herds, so double gateways (8 metres wide) or extended gates should be considered when installing gates.

The sun rises in the east and sets in the west, passing overhead slightly to the north around mid-day. Winter shading of laneways reduces the prospect of drying through sunlight and wind action on the laneway surface. Plant trees on the eastern side where possible.

Riparian Zones

Willows

Riparian land is any land that is next to, or directly influences a body of water. It includes areas adjacent to creeks and rivers, gullies and dips which sometimes run water, wetlands or areas surrounding dams and lakes.

|  |

- Where possible avoid direct stock access to a stream. If possible connect troughs to a permanent water supply such as a dam or reticulated water supply rather than from the stream. If necessary provide access points (e.g. concrete, gravel etc) in certain areas and fence the rest.

- Benefits of well managed intact riparian zones include: shelter for stock and pasture; improved water quality; improved habitat & wildlife; decrease in insect pests; opportunities for agroforestry; decreased light for algae; recreational area; reduced stream bank erosion, improved aesthetic value. Anecdotal evidence indicates that good riparian zones can increase property value by 10%.

|  A healthy riparian zone with a good mix of species and quatic vegetation. Photographs by: Rawdon Sthradher (Fine Focus Photography) |

Waterlogged pastures in winter and spring are a common occurrence on many farms in Southern Victoria. Some soils can not drain excess rainfall and become saturated. Waterlogging reduces soil strength, making it vulnerable to pugging and other damage when grazed and plants suffer due to lack of oxygen for root respiration.

There are two basic ways to overcome wet soils:

i). improve soil drainage so the removal of excess water is expedited (e.g. surface and sub-surface drainage).

ii). avoid intensive grazing of paddocks when wet as pugging damage is more likely to occur – try on-off grazing, feedpads, stand off areas.

The best time for farmers to assess the cause of their waterlogging problem, and therefore which drainage system is likely to be the most suitable, is when the soil is saturated (i.e. winter – early spring).

Depending on the severity of wet soils (i.e. length of time affected, % of farm affected, and how often it occurs) will help decide what option is needed on the farm. If it is a significant problem then consider drainage improvement together with on-off grazing.

Even if prolonged wet periods do not occur, it is still highly desirable to adopt an on-off grazing strategy to reduce pasture damage caused by pugging compaction during wet periods.

A trial showed that by November sub-surface drained pastures had much better pasture composition and density. Drained plots had double perennial ryegrass content, eight times the white clover content and a third of winter grass content than the comparable un-drained treatment.

Many landholders may be unsure of their soil types and what type of drainage method is best suited to their soil. It is important to select the most appropriate method based on soil characteristics. Mole drains, for example, will not be effective on permeable soils. Mole drains are designed for impermeable (i.e. high clay content) soils. Pipe drains will work on both permeable and impermeable soils, but on impermeable soils they need to be spaced so close together that they may become uneconomical.

Mole drains are unlined channels formed in a clay subsoil using a ripper blade with a cylindrical foot. They are used when natural drainage needs improving due to lack of slope or when a heavy clay subsoil prevents downward drainage.

Humps and hollows are useful in areas or on soil types that are not suitable for tile or mole drainage. They are also useful where the lack of suitable outfalls prohibit the use of tile drains, usually due to insufficient depth or fall.

An experienced drainage contractor can be most helpful in developing a plan of works. It should ideally cover 3-5 years of works.

‘Hump and hollowing’ is the practice of forming the ground surface into parallel convex surfaces separated by hollows. The humped shape sheds excess moisture relatively quickly while the hollows act as shallow surface drains.

Landcare Notes on the DEPI website

Farm drainage

Managing wet soils: case study of stand-off areas

Managing wet soils: case study of subsurface drainage (1)

Managing wet soils: case study of subsurface drainage (2)

Managing wet soils: feedpads and stand-off areas

Managing wet soils: grazing techniques

Managing wet soils: mole drainage

Managing wet soils: On-off grazing

Managing wet soils: Subsurface pipe drainage

Managing wet soils: renovation of damaged pastures and soils

Managing wet soils: surface drainage

Managing wet soils: what are your best options?

Managing wet soils: what off-paddock system?

Managing wet soils: Types of subsurface drainage?

Whole Farm Planning

- It is important to carefully plan changes on the farm before implementing them. The development of a land management or whole farm plan is an ideal way to identify issues, set priorities and plan how to address them on the farm.

- Many factors are combined in the planning of farm management and future developments including: paddock subdivision, access, crops, shelter, water supply, habitat, pest/weed control, fire protection, livestock needs, soil conservation, land degradation, water quality, labour, etc.

- To prepare a whole farm plan an accurate scale map or aerial photo of the property is required. Aerial photos of most areas are taken regularly, contact your local DEPI office for details.

- The mapping and planning process involves three plastic overlays (overlaying the photo). The first overlay records natural features of the land such as soil types, eroded and erosion prone areas, wet/low spots and waterbodies. The second overlay is based on the ideal layout (such as smaller paddocks, new laneways and extra trees). The third overlay includes the existing features such as laneways, fences and houses.

- Look at the overlays and see how the existing features can work towards achieving the “ideal” farm. For example, adjustments may be able to be made to existing fencing that will save money, as well as improving management and reducing time involved in moving stock.

- A whole farm plan does not need to ever finish – it can be regularly reviewed and updated.

- Once you have your photo, a great option is to do a WFP course. The advantages of these courses are they: a) give access to experts and information in particular fields (ie. erosion, subdivisions). b) encourage discussion and interchange of ideas between farmers, and c) ensure that the plan is largely complete. Courses usually run in the evening - contact your local DEPI, Landcare or TAFE for further information.

Biodiversity on Farms

An increasing number of studies are showing the benefits of wildlife and remnant vegetation.

These are examples of some of the findings from these studies:

- Between 40-60% of crows and ravens diet consists of insects including pasture cockchafers.

- Sugar gliders eat massive amounts of insects. Where enough winter food (mainly from wattles) is available, they will eat up to 18 000 scarab beetles per hectare per season. These insects may be tree defoliators, and their larvae pasture root eaters.

- Owls, hawks and eagles help control animal pests such as mice, rats, hares and rabbits.

- A study suggests that in healthy eucalypt woodlands, birds eat about half of the insects produced annually.

- Sheltered pastures lose 12 mm of water less than open pastures during the spring growing season.

- Sheltered areas have increases up to 17% (estimated) in dairy milk production and 20% (estimated) in average annual pasture growth for meat producers.

- On a day of 27C, unsheltered cows will produce 26% less dairy milk than shaded stock.

- Planting local trees, shrubs and groundcovers, rather than exotics or plants from other regions, provides food, shelter and nesting material for local wildlife. Using local plants also maximises the chance of restoring plant-animal interactions such as pollination and seed dispersal.

- Insectivorous birds including honeyeaters, consume about 24-38 kg of insects per hectare per year in Eucalypt woodlands.

Feedpads

- There are clear advantages in reducing pasture and soil damage: better pasture utilisation, increased pasture regrowth and improved animal welfare leading to increased production and fewer costs associated with pasture renovation. There are a number of options available if animals are to be taken off paddocks.

- A dairy feedpad is a confined yarded area that provides adequate water, space, feeding facilities and an effective effluent removal system. Stock can be held in the area for varying lengths of time. To reduce pasture damage, stock can be fed and held on the pad for a few hours each day or longer depending on the weather.

- Dairy feedpads are used throughout Australia to feed stock in times of pasture shortage, reduce the adverse effects of stock on pastures in wet weather, reduce pasture renovation costs and help adjust milk characteristics throughout controlled feeding. They are also used to facilitate higher stocking rates on farms of limited size.

- Avoid feedpads being situated adjacent to creeks or drainage lines to reduce risk of soil and nutrient movement to these waterways.

- You will need to consider enlarging your effluent system to cope with the additional loading from the feedpad. If possible have a separate effluent system for the feedpad areas, if not have some form of solids separation prior to entering the existing effluent system. Store over winter months to avoid run-off and reuse over pasture or crops.

- There are many types of feedpads that suit most situations and budgets. Many farmers have developed their own innovative feedpads by utilising or expanding existing infrastructure on the farm.

- Look around for ideas and don’t be afraid to ask questions and visit farms with systems that may suit your farm. Planning is very important.

- A feedpad becomes a permanent asset and can be used for the whole year. It can also be used for other activities such as calving, drafting, vet checking and as shade/shelter during adverse weather conditions.

Trees on Farms

Establishing Trees on Farms

|  |

|

|

Wet Areas on Farms

During wet times there will always be some run-off and the development of saturated areas around the property is likely to occur. Some parts of the landscape are generally wetter than others.

|  |

- Identify the main drainage lines on your farm as a separate land class in which vegetation needs to be retained and soil protected. Avoid cultivating these areas.

- Avoid straightening of drainage lines (through cleaning out). A straight channel has a higher velocity as it picks up speed down the slope. This will increase the potential for gully erosion and decrease infiltration to surrounding vegetation. Maintain vegetation in drainage lines – consider pasture or native trees/shrubs/understorey.

A wet area developed into a farm dam. Note the islands which provide wildlife habitat. |

|