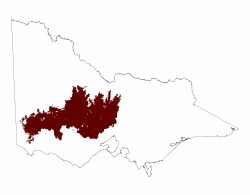

2. Western Uplands (WU)

Victoria's Geomorphological Framework (VGF)

2.1 Dissected Uplands

2.2 Strike ridges and valleys - Grampians Range

2.3 Low elevation plateaux (Tablelands)

| The Western Uplands of Victoria are the western part of the Victorian Highlands (Hills 1940) or Central Victorian Uplands as distinct from the Eastern Victorian Uplands (Jenkin 1988). The Western Uplands extend westwards from the Kilmore Gap (a geocol) to the western edge (Glenelg River) of the Dundas Tableland. They have been divided into the dissected uplands (2.1), sometimes referred to as the Midlands (Hills 1940; Jenkin 1988; Taylor et al. 1996); the strike ridges and valleys of the Grampians (2.2); and the tablelands (2.3), including the Dundas, Merino and Stavely Tablelands. The terrain is characterised by a suite of Palaeozoic bedrock formations that are now residuals due to differential erosion. Landforms are typically asymmetrical with gentle northern slopes and dissected southern slopes (Hills 1975). Resistant rock residuals include the granitic Harcourt batholith (Mt Alexander and Harcourt), the Cobaw Ranges, Mount Buangor and Mount Langi Ghiran; the rhyodacite massif of Mount Macedon; metamorphic ridges of Mt Tarrangower and Big Hill; Palaeozoic marine sediments of the Pyrenees Ranges and Trentham Dome; and the stratigraphic succession of quartzo-feldspathic sandstones of the Grampians Ranges. |  |

Recent stream dissection has stripped regolith and produced alluvial deposits and colluvial aprons fringing the margins of the Western Uplands. The main Divide separates north-flowing streams draining to the Northern Riverine Plains from south-flowing streams that have much steeper gradients owing to their closer proximity to the Victorian coastline. The Divide is ill defined (Hills 1975) due to extensive weathering of landscapes leaving ranges and ridges with extensive valley systems that do not resemble the well-defined ridge and valley relief of the Eastern Uplands. Lakes, often dry, and fringing lunettes, are found alng the Divide. Drainage systems flowing north as part of the Murray Darling Basin include the Campaspe, Loddon, Avoca, Wimmera, Avon and Richardson rivers while streams flowing towards the southern Victorian coastline include the Glenelg River, Wannon River, Hopkins River, Fiery Creek, Woady Yaloak Creek, Moorabool River, Leigh River, Werribee River, Maribynong River, Merri Creek, Kororoit Creek and Little River.

Nineteenth century gold mining has left a major imprint on the modern landscape. reducing forest cover, disturbing rock outcrops, drainage and flood plains, and producing post-contact deposits (Kotsonis and Joyce 2002) as thin sheets of alluvium downstream on valley floors or as alluvial fans onto the plains.