Tulip Prickly Pear (Opuntia phaeacantha)

Present distribution

|  This weed is not known to be naturalised in Victoria | ||||

| Habitat: Native to North America. Reported in various habitat from grassland to forest including at elevation. | |||||

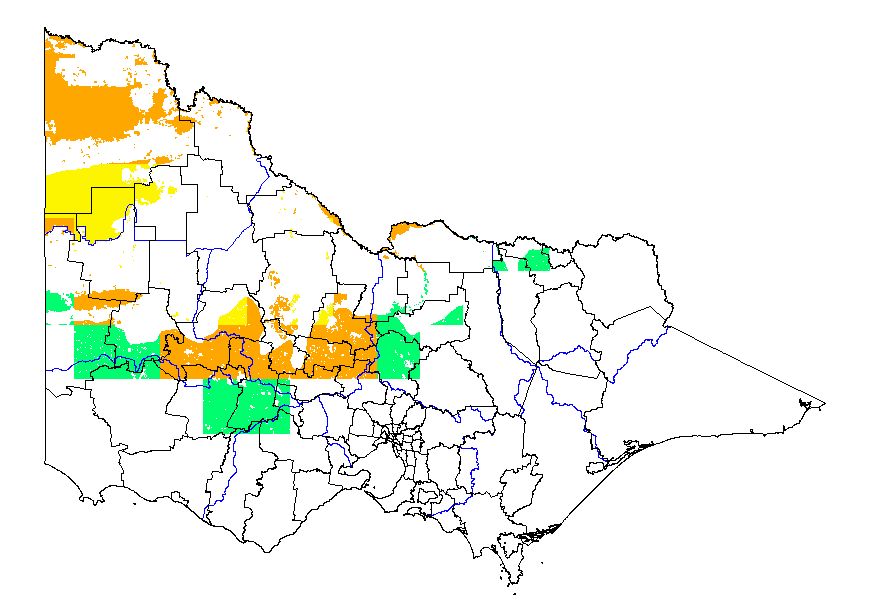

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Forest private plantation; forest public plantation; pasture dryland Broad vegetation types Coastal scrubs and grassland; coastal grassy woodland; heathy woodland; lowland forest; heath; box ironbark forest; inland slopes and plains; sedge rich woodland; dry foothills forest; montane dry woodland; sub-alpine woodland; grassland; plains grassy woodland; valley grassy forest; herb-rich woodland; sub-alpine grassy woodland; montane grassy woodland; riverine grassy woodland; rainshadow woodland; mallee; mallee heath; boinka-raak; mallee woodland; wimmera / mallee woodland Colours indicate possibility of Opuntia phaeacantha infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Low growing but sprawling, would impede people. | ml | m |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | May have a negative influence on aesthetics of an area. | ml | m |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Most varieties have spines (Benson 1982). | mh | m |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | No structural damage reported may have a negative influence on aesthetics. | ml | m |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Terrestrial species. | l | m |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Terrestrial species. | l | m |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | Has been found to reduce grazing pressure by restricting the movement of grazing species and sheltering grass/herb species in the vicinity of its spines. Therefore increasing the net ground cover and reducing the soil exposed to erosion (Price 1985). | l | m |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | By reducing grazing pressure may increase net biomass (Price 1985). | l | m |

| 9. Change fire regime? | If an increase in biomass does eventuate from the presence of O.phaeacantha, this increase in fire intensity would not be persistent as the cactus population left exposed after the fire would be reduced by herbiovry due to its now lack of spines (Bunting, Wright & Neuenschwander 1980). | l | m |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC= Plains Savannah (E); CMA= Wimmera; Bioreg= Lowan Mallee; H CLIMATE potential. Competitive in the shrub layer and alters species composition of ground layer. Major displacement of species. | mh | mh |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC= Semi-arid Woodland (D); CMA= Wimmera; Bioreg= Lowan Mallee; H CLIMATE potential. Competitive in the shrub layer and alters species composition of ground layer. Major displacement of species. | mh | mh |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC= Red Swale Mallee (LC); CMA= Wimmera; Bioreg= Lowan Mallee; H CLIMATE potential. Competitive in the shrub layer and alters species composition of ground layer. Major displacement of species. | mh | mh |

| 11. Impact on structure? | Low growing shrub, may alter the composition of the grass/herb layer in its vicinity, to those more sensitive to grazing (Price 1985 and Rebollo etal 2002). | ml | m |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | May protect species sensitive to grazing (Price 1985 and Rebollo etal 2002). | m | ml |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | No specific data. | mh | l |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | Invading grassland, it creates a shruby layer previously not there. | l | ml |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | May be a food source, especially in drought. Spiny growth may shelter small species. | mh | m |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | Does have spines (Benson 1982). | mh | m |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | Eaten by goats (McMillan etal 2002). | ml | m |

| 18. Provides harbor? | No specific data, not thought any more than other shrubby species. | m | ml |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | Reduces forage by restricting access (Price 1985), may be a source of fodder during drought (McMillan etal 2002). | ml | m |

| 20. Impact quality? | No specific data. | l | ml |

| 21. Affect land value? | If control view necessary may have negative influence on land value. | m | ml |

| 22. Change land use? | Most prevalent in pastoral systems which can't really be further downgraded. | ml | m |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | If restrict stock movement may increase mustering times. | mh | m |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Not reported. | l | m |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | Under experimental conditions optimum temperature for germination was between 25-35 C, and leaching in water also helped germination, therefore a period over the growing season when there is sufficient water, it is presumed that O. phaeacantha will germinate. Also like other opuntia sp. it is presumed that vegetative propagules only requirement for setting root is sufficient water (Potter, Peterson & Ueckert 1984). | h | m |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | Not specified reported in woodland and montane forest therefore must be able to establish under some shade (Benson 1982). | mh | m |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Present in grassland and woodland (Benson 1982). | mh | m |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | A large, prostrate or sprawling cactus (Benson 1982). | l | m |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | None described | l | m |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Used as emergency fodder during drought (McMillan etal 2002), susceptible to herbiovoury after fire when its spines have been removed, can result in up to 80% mortality in a population (Bunting, Wright & Neuenschwander 1980). | m | m |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | A prostrate plant, reported up to 0.9m high x 2.5m in diameter, with an annual productivity has been estimated between 1.5kg and 2kg per plant (Nisbet 1972). No comparison is able to be made at this point with other cactus species, however with the dimensions in comparison to the size other species grow, growth rate is below average (Benson 1982). | ml | m |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | The plants that aren't killed by the fire are often left exposed to increased herbivory due to their spines being singed off (Bunting, Wright & Neuenschwander 1980). Used as an emergency fodder during a drought can therefore tolerate drought (McMillan etal 2002). Recorded at over 2000m therefore exposed and tolerant of frost conditions (Benson 1982). | mh | m |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | One of the few opuntia species that is self compatible, produces seed bearing fruit. Broken segments are also vegetative propagules (Benson 1982). | h | m |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | No specific figures, however from images can be viewed producing numerous fruits with numerous seeds (Benson 1982). | h | m |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | Unknown | m | l |

| 12. Reproductive period? | Life span of species not reported, however many opuntia species reported to live 10+ years and for all this time they can at least reproduce vegetatively. | h | m |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | May be able to produce vegetative propagules within one year. | h | m |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Fruit reportadly eaten by cattle and seeds deposited had a high germination rate than those removed from ripe fruit (Potter, Peterson & Ueckert 1984). | mh | mh |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | Cattle can move many kilometres in the time taken for seeds to pass through their digestion. | h | m |

References

Benson. L. (1982) The Cacti of the United States and Canada. Stanford University press, Stanford, California.

Bunting. S.C., Wright. H.A. & Neuenschwander. L.F. (1980) Long-term effects of fire on cactus in southern mixed prairie of Texas. Journal of Range Management. 33: 85-88.

Hubert. E.W. (1980) Cacti of the Southwest : Arizona, western New Mexico, southern Colorado, southern Utah, southern Nevada, eastern California. Rancho Arroyo

McMillan. Z., Scott. C.B., Taylor. C.A. Jr. & Huston. J.E. (2002) Nutritional value and intake of prickly pear by goats. Journal of Range Management. 55: 139-143.

Nisbet. R.A. (1972) Producticity and temperature acclimation in a prickly-pear cactus in south-central Arizona. Dissertation Abstracts International, B.. 33: 1961-1962.

Potter. R.L., Peterson. J.L. & Ueckert. D.N.(1984) Germination responses of Opuntia spp. to temperature, scarification, and other seed treatments. Weed Science. 32: 106-110

Price. D.L., Heitschmidt. R.K., Dowhower. S.A. & Frasure. J.R. (1985) Rangeland vegetation response following control of browns pine pricklypear (Opuntia phaecantha) with herbicides. Weeds Science. 33: 640-643.

Rebollo. S., Milchunas. D.G., Noy-Meir. I. & Chapman. P.L. (2002) The role of a spiny plant refuge in structuring grazed shortgrass steppe plant communities. Oikos. 98: 53-64.

Global present distribution data references

Calflora: Information on California plants for education, research and conservation. [web application]. 2006. Berkeley, California: The Calflora Database [a non-profit organization]. Available: http://www.calflora.org/ . (Accesses: Aug 29, 2006)

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2006, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed Aug 29 2006, http://www.gbif.org/

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) 2006, w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, viewed Aug 29 2006, http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.