Grey Cotoneaster (Cotoneaster franchetii)

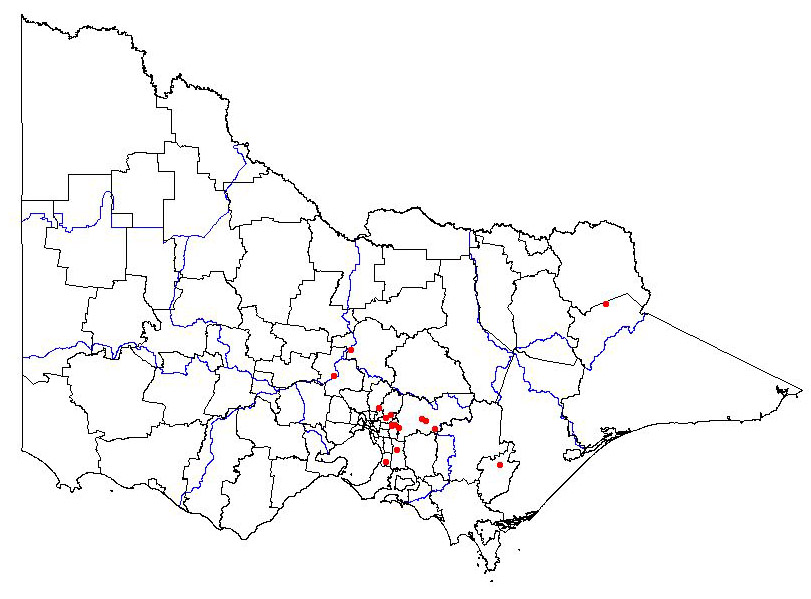

Present distribution

|  Map showing the present distribution of this weed. | ||||

| Habitat: Reported to invade forest, woodland, grassland, scrub, riparian areas, roadsides and waste places (Bossard, Randell & Hoshovsky 2000; Dept. Conservation N.Z.; Henderson 1993 and Webb, Sykes & Garnock-Jones 1988) Is also reported to be tolerant of maritime exposure (PFAF 2002). | |||||

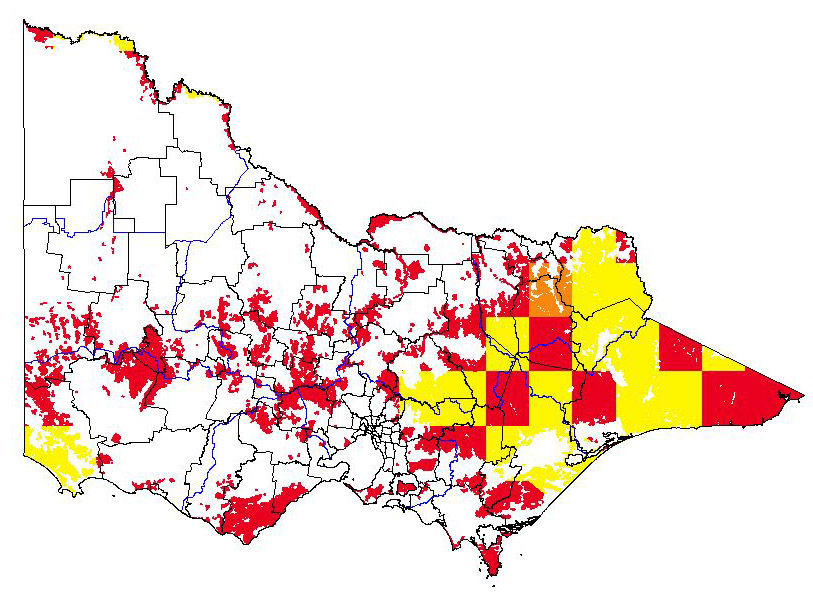

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Forest private plantation; forest public plantation; horticulture Broad vegetation types Coastal scrubs and grassland; coastal grassy woodland; heathy woodland; lowland forest; box ironbark forest; inland slopes woodland; sedge rich woodland; dry foothills forest; moist foothills forest; montane dry woodland; montane moist forest; sub-alpine woodland; grassland; plains grassy woodland; valley grassy forest; herb-rich woodland; sub-alpine grassy woodland; montane grassy woodland; riverine grassy woodland; riparian forest; rainshadow woodland; wimmera / mallee woodland Colours indicate possibility of Cotoneaster franchetii infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Can be used as a hedge, present as thickets in its native environment (PFAF 2002). Significant works would be required to clear thicket for access, once plants established. | h | m |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | Ornamental species may alter the aesthetics. | ml | l |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Cotoneaster berries contain a cyanogenic glycoside and are poisonous if consumed in large quantities, especially to children (Shepherd 2004). In 1983-84 1.29% of the reports involving plants made to the Poisons centres in Australia involved a Cotoneaster species (Covacevich, Davie & Pearn 1987). | ml | mh |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | Ornamental species may alter the aesthetics. Has aggressive root system, may therefore cause structural damage (Bossard, Randell & Hoshovsky 2000). | m | l |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Terrestrial species | l | m |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Terrestrial species | l | m |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | Cotoneaster species have been used for soil conservation in their native range (Singh, Bhagwati & Nawa 1992). | l | mh |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | Unknown; reported to form dense thickets, which could be an increase in biomass of the woodland that it has invaded (PFAF 2002). However Cotoneaster species are reported to be able to prevent the native shrubs and trees from regenerating (Bossard, Randell & Hoshovsky 2000). Therefore in the short term biomass may increase, while in the long term a woodland or forest may become a shrubland decreasing biomass. | m | m |

| 9. Change fire regime? | Unknown, however a change in biomass could alter the fire intensity. | ml | ml |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC= Grassy Woodland (E); CMA Corangamite; Bioreg Otway Ranges; VH CLIMATE potential. Can form pure stands, out competing native species (Dept. Conservation NZ 2002). Therefore cause major displacement of species. | mh | mh |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC= Herb-rich Foothill Forest (D); CMA Corangamite; Bioreg Otway Ranges; VH CLIMATE potential. Can form pure stands, out competing native species (Dept. Conservation NZ 2002). Therefore cause major displacement of species. | mh | mh |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC= Riparian Forest (LC); CMA Corangamite; Bioreg Otway Ranges; VH CLIMATE potential. Can form pure stands, out competing native species (Dept. Conservation NZ 2002). Therefore cause major displacement of species. | mh | mh |

| 11. Impact on structure? | Can form pure stands, out competing native species (Dept. Conservation NZ 2002). Therefore cause major displacement of species. | mh | mh |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | Unknown. | mh | l |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | Unknown. | mh | l |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | Alteration of habitat, forming the major part of the plant community, creating dense thickets (Dept. Conservation NZ 2002). Therefore diversity in available food and shelter could be reduced. | mh | mh |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | Additional food source through berries for bird species (Blood 2001). Dense shrubby vegetation used for nesting sites by bird species (Lu, Zhang & Ren 2003). | m | m |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | Contains a cyanogenic glycoside and is toxic to people (Shepherd 2004). However no detrimental effects to fauna reported, birds eat and disperse the berries (Blood 2001). | l | mh |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | Red berries attractive to frugivorous bird species (Blood 2001). Visited by bees (PFAF 2002). | ml | mh |

| 18. Provides harbor? | Cotoneaster species have been reported used as nesting sites by turtle-doves (Lu, Zhang & Ren 2003). Creates thickets (PFAF 2002). Thickets may provide shelter for foxes and rabbits | m | m |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | Not an agricultural weed | l | m |

| 20. Impact quality? | Not an agricultural weed | l | m |

| 21. Affect land value? | Not an agricultural weed | l | m |

| 22. Change land use? | Not an agricultural weed | l | m |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | Not an agricultural weed | l | m |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Can be infected by fireblight however selective breeding towards resistance may have reduced the occurrence of this (Persiel & Zeller 1990). Susceptible to honey fungus (PFAF 2002). | h | m |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | For propagation of cotoneaster species, seed is recommended to be sown in autumn, or stratified over winter and then sown under glass in spring (Griffths 1992). Therefore there is a seasonal component to the germination of cotoneaster species. | mh | m |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | Tolerant of full shade (PFAF 2002) | mh | m |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Has invaded areas of scrub, forest margins and riparian areas in New Zealand (Webb, Sykes & Garnock-Jones 1988). | mh | mh |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Shrub (Walsh & Entwisle 1996). | l | mh |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | No reported for this species, however C. salicifolius has been reported to allelopathic potential (Morita, Ito & Harada 2005). | m | l |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Not reported grazed, tolerant of pruning (PFAF 2002). | mh | m |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Not specifically known however Cotoneaster species in general are known to be fast growing (Bossard, Randell & Hoshovsky 2000). | mh | m |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Tolerant of temperatures to –15C (frost) (PFAF 2002). Drought resistant (Bodkin 1986). Tolerant of salt spray (PFAF 2002). Susceptible of waterlogging (PFAF 2002). | mh | m |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | Reproduces sexually, producing seed (Persiel & Zeller 1990). Cotoneaster species are capable of layering, where branches that are in constant contact with the ground can set root (Bossard, Randell & Hoshovsky 2000). | h | mh |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | Produces abundant fruit, each usually containing 3 seeds (Shepherd 2004). | h | mh |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | Due to the seeds germinating after a 14 month stratification study on C. horizontalis, seed viability was at 38% (Blomme & Degeyter 1985). Unknown however how long a seed can remain viable. | m | l |

| 12. Reproductive period? | Large shrub species; presumed capacity to produce fruit 10+ years. | h | ml |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | Unknown | m | l |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Produces red berries, which are then dispersed by birds and animals (Blood 2001 and Muyt 2001). | h | mh |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | Birds and animals can disperse fruit seeds distances greater than 1 km (Spennemann & Allen 2000). | h | mh |

References

Blomme R. & Degeyter L., 1985, Seed treatments and germination determinations for seeds of Cotoneaster horizontalis. Verbondsnieuws voor de Belgische Sierteelt. 29: 17-23

Blood K., 2001, Environmental Weeds. A field guide for SE Austalia. CH Jerram & Associates – Science publishers. Mt Waverly.

Bodkin F., 1986, Encyclopaedia Botanica : the essential reference guide to native and exotic plants in Australia. Angus & Robertson.

Bossard C.C., Randell J.M. & Hoshovsky M.C., 2000, Invasive plants of California’s wildlands. University of California Press.

Covacevich J., Davie P. & Pearn J., 1987, Toxic plants & animals. A guide for Australia. Queensland Museum. Brisbane

Department of Conservation, Wellington Conservancy, New Zealand, 2002, Plant me instead: plants to use in place of common and invasive environmental weeds in the lower North Island. Department of Conservation, Wellington Conservancy, New Zealand

Griffths M., 1992, The new Royal Horticultural Society dictionary of gardening. Macmillan. London

Henderson.L., 1995, Plant Invaders of Southern Africa: Plant Protection Research Institute Handbook No 5. Agricultural Research Council.

Lu X., Zhang L.Y., & Ren C., 2003, Breeding ecology of the rufous turtle dove (Streptopelia orientalis) in mountain scrub vegetation, Lhasa (Tibet). Game & Wildlife Science. 20: 225-240

Morita S., Ito M. & Harada J., 2005, Screening of an allelopathic potential in arbor species. Weed Biology and Management. 5: 26-30

Muyt A., 2001, Bush invaders of south-east Australia: a guide to the identification and control of environmental weeds in south-east Australia, R.G. and F.J. Richardson, Collingwood.

Persiel F. & Zeller W., 1990, Breeding upright growing types of cotoneaster for resistance to fireblight, Erwinia amylovora (Burr.) Winslow et al. Acta Horticulturae. 273: 297-301

PFAF: Plants for a Future. Edible, medicinal and useful plants for a healthier world. viewed 22 Feb 2002, http://pfaf.org/

Singh R.P., Bhagwati P. & Nawa B., 1992, Cotoneaster microphylla Wall. – suitable for soil conservation in temperate regions of Himalayas. Indian Forester. 118: 672-675

Shepherd R.C.H., 2004, Pretty but poisonous. Plants poisonous to people, an Illustrated Guide for Australia. R.G. and F.J. Richardson. Meredith

Spennemann. D.H.R. & Allen. L.R., 2000, Feral olives (Oliea europaea) as future woody weeds in Australia: a review. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture. 40: 889-901.

Walsh N.G. & Entwisle T.J., 1996, Flora of Victoria. Volume 3. Dicotyledons Winteraceae to Myrtaceae. Inkata Press. Melbourne

Webb C.J., Sykes W.R. & Garnock-Jones P.J., 1988, Flora of New Zealand, Vol 4, Botany Division, Department of Scientific & Industrial Research, New Zealand.

Global present distribution data references

FIS: Flora Information System 2005. Department of Sustainability and Environment.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2006, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed 1 Dec 2006, http://www.gbif.org/

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) 2006, w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, viewed 1 Dec 2006, http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.