Common pokeweed (Phytolacca americana)

Present distribution

|  This weed is not known to be naturalised in Victoria | ||||

| Habitat: Native to southeastern Canada, eastern United States and northeast Mexico (Sauer, 1952) and naturalised throughout the world (Hanf, 1983), including New South Wales and Queensland (Hewson, 1984) and New Zealand (Webb et al, 1988). Recorded in waste land, scrub margins, around old homesteads (Webb et al, 1988); ruderal sites, hedgerows, vineyards (Hanf, 1983); along roadsides, in clearings, around barnyards and in uncultivated soils (Mitich, 2005); crops (Bostian et al, 1999); upper and lower coastal plain (Caulkins & Wyatt, 1990); damp river bottom woods, well-drained open uplands, old orchards, gardens, old pastures, ravines, river banks, low woods near creek, woods flooded in spring, alluvial woods, low ground; not present in mountain areas (Sauer, 1952). | |||||

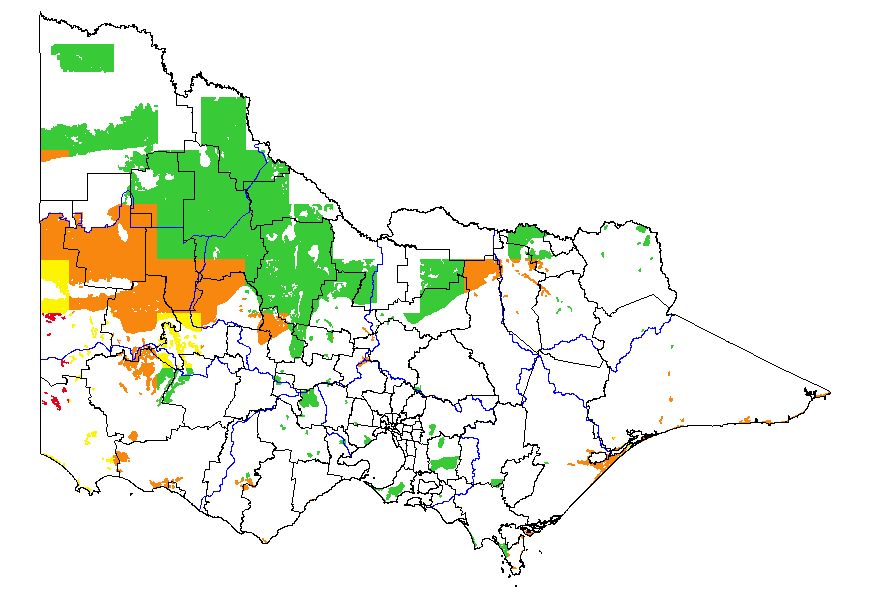

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Broadacre cropping; horticulture. Broad vegetation types Coastal scrubs and grassland; coastal grassy woodland; inland slopes woodland; sedge rich woodland; grassland; plains grassy woodland; herb-rich woodland; riverine grassy woodland. Colours indicate possibility of Phytolacca americana infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | “A dense herbaceous cover [was] dominated by pokeweed…nearly 2m tall” (Torbert & Johnson, 1993). Given this plant’s ability to colonise raw river alluvium (Sauer & Struik, 1964), it could restrict access to waterways for humans. Its herbaceous (He et al, 2005) nature probably allows passage with some effort, but is unlikely to prove impassable. | MH | H |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | “A dense herbaceous cover [was] dominated by pokeweed…nearly 2m tall” (Torbert & Johnson, 1993). Given this plant’s ability to colonise raw river alluvium (Sauer & Struik, 1964), it would be obvious to the average visitor but is unlikely to prevent recreation along a whole river stretch. | ML | H |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Can be fatal to humans (Mitich, 2005). | H | MH |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | Herbaceous plant (He et al, 2005). Unlikely to damage cultural sites. | L | H |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Despite being able to colonise raw river alluvium (Sauer & Struik, 1964), there is no evidence that pokeweed impacts on waterways in the substantial literature of this plant. | L | MH |

| 6. Impact water quality? | Despite being able to colonise raw river alluvium (Sauer & Struik, 1964), there is no evidence that pokeweed impacts on waterways in the substantial literature of this plant. | L | MH |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | Perennial rootsystem (Mitich, 2005). Unlikely to increase soil erosion. | L | MH |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | Grows in open disturbed areas, particularly forest edges and canopy gaps (He et al, 2005). Colonises raw river alluvium, forest blowdown, landslides (Sauer & Struik, 1964). Rarely the dominant member of natural communities (Cahill & Casper, 1999). As this plant tends to invade bare areas, it has the potential to increase biomass. | L | H |

| 9. Change fire regime? | As a semi-succulent (Webb et al, 1988) perennial herb (He et al, 2005) to 3.5m (Mitich, 2005), this plant has the potential to reduce the incidence and intensity of fires, but as it tends to invade highly disturbed areas (Sauer & Struik, 1964), and is addressed as a weed of agriculture (Sellers et al, 2006), it is unlikely to have much affect. | L | MH |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC=Plains grassy woodland (E); CMA=Wimmera; Bioreg= Wimmera; CLIMATE potential=VH. “Except in some row-crop situations, pokeweed rarely infests large areas and is usually found in isolated instances” (Sellers et al, 2006). Sparse/scattered infestations. | L | MH |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC=Heathy herb rich woodland (D); CMA=Glenelg Hopkins; Bioreg=Glenelg Plain; CLIMATE potential=VH. “Except in some row-crop situations, pokeweed rarely infests large areas and is usually found in isolated instances” (Sellers et al, 2006). Sparse/scattered infestations. | L | MH |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC=Coastal tussock grassland (LC); CMA=West Gippsland; Bioreg=Gippsland Plain; CLIMATE potential=H. “Except in some row-crop situations, pokeweed rarely infests large areas and is usually found in isolated instances” (Sellers et al, 2006). Sparse/scattered infestations. | L | MH |

| 11. Impact on structure? | “Except in some row-crop situations, pokeweed rarely infests large areas and is usually found in isolated instances” (Sellers et al, 2006). Growing to 3.5m (Mitich, 2005), it may have a minor effect on the grass and shrub layers, but unlikely to impact on the tree layer. | ML | MH |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | “Except in some row-crop situations, pokeweed rarely infests large areas and is usually found in isolated instances” (Sellers et al, 2006). May have a minor effect on threatened grass or shrub species. | ML | MH |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | “Except in some row-crop situations, pokeweed rarely infests large areas and is usually found in isolated instances” (Sellers et al, 2006). May have a minor effect on threatened fauna, reducing habitat or food sources to a minimal degree. | ML | MH |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | “Except in some row-crop situations, pokeweed rarely infests large areas and is usually found in isolated instances” (Sellers et al, 2006). May have a minor effect on non-threatened fauna, reducing habitat or food sources to a minimal degree. | ML | MH |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | “Except in some row-crop situations, pokeweed rarely infests large areas and is usually found in isolated instances” (Sellers et al, 2006). Poisonous and unpalatable (OARDC, 2006) and unlikely to grow densely enough to shelter desireable fauna species. | ML | MH |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | Poisonous due to a high level of saponins. Ripe berries have a molluscicidal effect, but only at levels described as “not economically viable,” (Aldea & Allen-gil, 2005) suggesting that it would require more than a riparian infestation to affect aquatic animals. All parts are toxic to humans, pets and livestock, but not very palatable and avoided by most animals, unless there is little else to eat (OARDC, 2006). May cause loss of condition if eaten. | ML | M |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | All parts are toxic to humans, pets and livestock, but not very palatable and avoided by most animals, unless there is little else to eat (OARDC, 2006). “At times the berries form one of the chief foods of the small migratory birds” (Mitich, 2005). May provide food for minor pest species, such as birds. | ML | MH |

| 18. Provides harbour? | “Except in some row-crop situations, pokeweed rarely infests large areas and is usually found in isolated instances” (Sellers et al, 2006). Unlikely to grow densely enough to harbour pest species. | L | MH |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | “Very competitive to row crops, directly decreasing yield” (Steckel, 2006). Can invade pastures and is poisonous to livestock (OARDC, 2006). Major impact. | MH | M |

| 20. Impact quality? | “Berries can stain soybean seed during harvest,” which, in the US, must be removed to assign a grade to the produce (Steckel, 2006). Can contaminate hay, and can poison livestock in green fodder (OARDC, 2006). Produce may be rejected for sale. | H | M |

| 21. Affect land value? | No evidence that land value is affected. | L | L |

| 22. Change land use? | Able to be controlled easily (Bostian et al, 1999). Change of land use not required. | L | MH |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | No evidence of increased harvest costs. | L | L |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | None found. | L | L |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | Passage through bird gut increased the rate of germination and the proportion of seed germinating, but was not required for germination to occur (Orrock, 2005). Seed can germinate without cold stratification (Caulkins & Wyatt, 1990). Seedlings emerge from mid-spring to early summer (OARDC, 2006). Requires seasonal conditions to germinate. | MH | M |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | Grows in shaded sites (Webb et al, 1988), but seedlings are slow-growing and unable to compete with other herbs (Sauer, 1952) | MH | MH |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Grows in open disturbed areas, particularly forest edges and canopy gaps (He et al, 2005). Colonises raw river alluvium, forest blowdown, landslides (Sauer & Struik, 1964). Major disturbance required. | L | H |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Semi-succulent (Webb et al, 1988) perennial herb (He et al, 2005) to 3.5m (Mitich, 2005). | L | MH |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | Leaf extracts are able to inhibit seed germination (Kim et al, 2005). Demonstrated experimentally for two species. Some species seriously affected. | MH | H |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Recovers quickly from foliage removal via herbicide application (Steckel, 2006. Seldom eaten by cattle (Sauer, 1952). Consumed, but not preferred, and capable of rapid recovery. | MH | H |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Can reach 1.85m after 8 weeks (Bostian et al, 1999). Very rapid. | H | MH |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | Hardy, winter dormancy, tolerates temperatures down to -15oC (Mitich, 2005). High fire tolerance; Low tolerance of anaerobic soil; moderate drought tolerance (USDA, 2006). High frost and fire tolerance, moderate drought tolerance, low anaerobic soil tolerance suggests low waterlogging tolerance. | MH | M |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | Predominantly autogamous [self-fertile] (He et al, 2005). Reproduces from buds on the roots or from seeds (Bostian et al, 1999). | H | MH |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | Over 48 000 per plant (Sellers et al, 2006) | H | M |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | At least 39 years (Sauer, 1952). | H | H |

| 12. Reproductive period? | Over a three year period, plants were observed to persist in a healthy state (Sauer, 1952), presumable still able to flower. | MH | H |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | Can grow to reproductive maturity within a single season (He et al, 2005) | H | H |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | Spread by birds (Orrock, 2005). | H | H |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | “At times the berries form one of the chief foods of the small migratory birds” (Mitich, 2005). Very likely that many propagules will spread much more than 1 km. | H | MH |

References

Aldea, M & Allen-gil, S 2005, ‘Comparative Toxicity of Pokeweed (Phytolacca Americana) Extracts to Invasive Snails (viviparous georgianis) and Fathead Minnows (Pimephales promelas) and the Implication for Aquaculture,’ Bulletin Environmental Cntamination and Toxicology, vol. 74, pp. 822-829.

Bostian, TL Witt, WW & Green, JD 1999, ‘Effects of cultural practices on common pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) control in no-till soybean production,’ Proceedings, Southern Weed Science Society, vol. 52, p. 41.

Caulkins, D.B. & Wyatt, R. 1990, ‘Variation and taxonomy of Phytolacca Americana and P. rigida in the southeastern United States,’ Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, vol. 117(4), p. 357-367.

Cahill, J.F & Casper, B.B. 1999, ‘Growth Consequences of Soil Nutrient Heterogeneity for tow Old-field Herbs, Ambrosia artemisiifolia and Phytolacca americana, Grown Individually and in Combination,’ Annals of Botany, vol. 83(4), p. 471.

Kim, Y.O. Johnson, J.D. Lee, E.J. 2005, ‘Phytotoxic effects and chemical analysis of leaf extracts from three Phytolaccaceae species in South Korea,’ Journal of chemical ecology, Vol. 31(5), pp. 1175-1186.

He, J.S. Wolfe-Bellin, K.S. & Bazzaz, F.A. 2005, ‘Leaf-level physiology, biomass, and reproduction of Phytolacca americana under conditions of elevated CO2 and altered temperature regimes,’ International journal of plant sciences, Vol. 166(4), pp. 615-622

Hewson H.J. 1984 ‘Phytolaccaceae,’ in George, A.S. (ed) Flora of Australia, vol. 4, pp. 1-4.

Mitich, L.W. 2005, ‘Common Pokeweed,’ Weed Science Society of America, Kansas, viewed: 10/11/2006, www.wssa.net/photo&info/weedstoday_info/pokeweed.htm

Orrock, J.J. 2005, ‘The effect of gut passage by two species of avian frugivore on seeds of pokeweed, Phytolacca Americana,’ Canadian journal of botany, Vol. 83(4), pp. 427-431.

Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center (OARDC) 2006, Ohio Perennial and Biennial Weed Guide – Common Pokeweed, The Ohio State University, USA, viewed: 10/11/2006, http://www.oardc.ohio-state.edu/weedguide/singlerecordframe2.asp?id=270

Sauer, J. 1952, ‘A geography of pokeweed,’ Annals of the Missouri Botanic Gardens, vo. 39(2), p. 113-125.

Sauer, J. & Struik, G. 1964, ‘A possible ecological relation between soil disturbance, light-flash and seed germination,’ Ecology Vol. 45, p. 884–886.

Sellers, B. Ferrell, J. & Ranbolt, c. 2006, ‘Common Pokeweed SS_AGR-123,’ University of Florida IFAS Extension, USA, viewed: 23/11/2006, http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/AG/AG25400.pdf

Steckel, L. 2006, ‘Common Pokeweed W105,’ The University of Tennessee Extension, USA, viewed:23/11/2006, www.utextension.utk.edu/publications/wfiles/W105.pdf

Torbert, JS & Johnson, JE 1993, ‘Establishing American sycamore seedlings on land irrigated with paper mill sludge,’ New Forests, vol. 7(4), pp. 305-317.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) 2006 ‘Conservation Plant Characteristics for: Phytolacca americana L. American pokeweed PHAM4,’ United States Department of Agriculture, USA, viewed: 23/11/2006, http://plants.nrcs.usda.gov/cgi_bin/topics.cgi?earl=plant_attribute.cgi&symbol=PHAM4

Webb, CJ Sykes, WR & Garnock-Jones PJ 1988, Flora of New Zealand, Christchurch, New Zealand

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) 2006, Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, viewed: 22/11/2006, http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/

Bostian, TL Witt, WW & Green, JD 1999, ‘Effects of cultural practises on common pokeweed (Phytolacca americana) control in no-till soybean production,’ Proceedings, Southern Weed Science Society, vol. 52, p. 41.

Caulkins, D.B. & Wyatt, R. 1990, ‘Variation and taxonomy of Phytolacca Americana and P. rigida in the southeastern United States,’ Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club, vol. 117(4), p. 357-367.

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) 2006, Global biodiversity information facility: Prototype data portal, viewed 22/11/2006, http://www.gbif.org/

Hanf, M. 1983, The arable weeds of Europe with their seedlings and seeds, BASF, UK.

Hewson, H.J. 1984, ‘Phytolaccaceae,’ in George, A.S. (ed) 1984, Flora of Australia, vol. 4, p 1-4.

Missouri Botanical Gardens (MBG) 2006, w3TROPICOS, Missouri Botanical Gardens Database, viewed: 22/11/2006, http://mobot.mobot.org/W3T/Search/vast.html

Mitich, L.W. 2005, ‘Common Pokeweed,’ Weed Science Society of America, Kansas, viewed: 10/11/2006, www.wssa.net/photo&info/weedstoday_info/pokeweed.htm

Sauer, J. 1952, ‘A geography of pokeweed,’ Annals of the Missouri Botanic Gardens, vo. 39(2), p. 113-125.

Webb, CJ Sykes, WR & Garnock-Jones PJ 1988, Flora of New Zealand, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.