Africa lily (Agapanthus africanus)

Present distribution

|  This weed is not known to be naturalised in Victoria | ||||

| Habitat: Grows on mountain coastal ranges (Rodríguez 1997), rocky places on mountains (Burman, Bean 1985), between rocks and in depressions on sheets of sandstone rock (Jamieson 2004), subsurface wetlands (Zurita et al. 2009), in bushland in remnant endangered ecological community, Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest (Abell 2005). Salt tolerant (Harrison 2006), acidic sandy soil (Jamieson 2004), Agapanthus spp. “will grow in any kind of soil – clay, sand or gravel” (van der Spuy 1971), permanently wet situations and dry, hot locations (Zonneveld, Duncan 2006), from sea-level mountain tops and occur always in places where the rainfall is more than 500 mm a year in its native range (van der Spuy 1971). | |||||

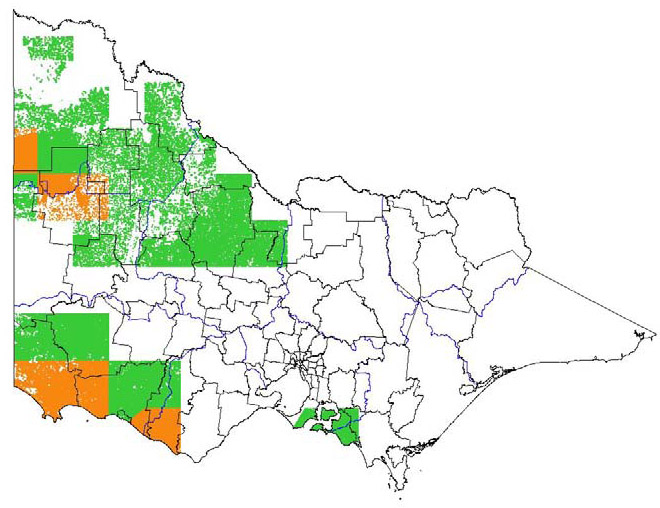

Potential distribution

Potential distribution produced from CLIMATE modelling refined by applying suitable landuse and vegetation type overlays with CMA boundaries

| Map Overlays Used Land Use: Pasture dryland; pasture irrigated Ecological Vegetation Divisions Coastal; heathland; grassy/heathy dry forest; swampy scrub; freshwater wetland (permanent); treed swampy wetland; lowland forest; foothills forest; forby forest; damp forest; riparian; wet forest; high altitude shrubland/woodland; granitic hillslopes; rocky outcrop shrubland; western plains woodland; alluvial plains woodland; ironbark/box; riverine woodland/forest; freshwater wetland (ephemeral); lowan mallee; broombush whipstick Colours indicate possibility of Agapanthus africanus infesting these areas. In the non-coloured areas the plant is unlikely to establish as the climate, soil or landuse is not presently suitable. |

|

Impact

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Social | |||

| 1. Restrict human access? | Flowering stems to about 60 cm (van der Spuy 1971) – minimal or negligible impact | l | h |

| 2. Reduce tourism? | Occurs in bushland in remnant endangered ecological community, Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest (Abell 2005), grows to 60 cm (van der Spuy 1971) flowers blue, rarely white (Jamieson 2004) – minor effects to aesthetics | ml | m |

| 3. Injurious to people? | Causes skin rashes and may cause damage to eyes, mouth and throat on contact (Toronto Botanical Garden 2009) – causes serious allergies to humans throughout the year | h | ml |

| 4. Damage to cultural sites? | Grows to 60 cm (van der Spuy 1971) flowers blue, rarely white (Jamieson 2004) – moderate visual effect in historic gardens | ml | m |

| Abiotic | |||

| 5. Impact flow? | Can grow in wetlands (Zurita et al. 2009) – may have a minor impact on surface or subsurface flow | ml | m |

| 6. Impact water quality? | With Zantedeschia aethiopica, Strelitzia reginae and Anturium andreanum, Agapanthus africanus has been found to reduce pollutants in constructed wetlands, lowering BOD, COD, Org-N, NH4, Total-P and TC (Zurita et al. 2009) – no noticeable effect on dissolved oxygen or light levels | l | h |

| 7. Increase soil erosion? | As a soil conservation measure hedgerows of A. africanus was not as efficient as Vetiveria zizaniodes and Nephrolepis sp., however hedgerows of A. africanus resulted in less soil loss in simulated rain events than plots with no hedgerows (Rodríguez 1997) – low probability of large scale soil movement; OR decreases the probability of soil erosion | l | h |

| 8. Reduce biomass? | Occurs in bushland in remnant endangered ecological community, Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest (Abell 2005), however has only an average growth rate (NGA 2009) – biomass slightly decreased | mh | m |

| 9. Change fire regime? | Occurs in bushland in remnant endangered ecological community, Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest (Abell 2005) and “Blooms profusely after veld fires” (Burman, Bean 1985) – not likely to change fire regime – small or negligible effect on fire risk | l | m |

| Community Habitat | |||

| 10. Impact on composition (a) high value EVC | EVC = Sedgey Riparian Woodland (E); CMA = Corangamite; Bioregion = Warrnambool Plain; M CLIMATE potential. It occurs in bushland (Abell 2005), mountainous terrain growing between rocks and even in depressions on sheets of sandstone rock (Jamieson 2004) and can grow in wetlands (Zurita et al. 2009), it is also clump forming (Hitchmough 1989) Major displacement of some dominant spp. within a strata/layer | mh | h |

| (b) medium value EVC | EVC = Riparian Scrub (D); CMA = Glenelg Hopkins; Bioregion = Glenelg Plain; M CLIMATE potential. M It occurs in bushland (Abell 2005), mountainous terrain growing between rocks and even in depressions on sheets of sandstone rock (Jamieson 2004) and can grow in wetlands (Zurita et al. 2009), it is also clump forming (Hitchmough 1989)ajor displacement of some dominant spp. within a strata/layer | mh | h |

| (c) low value EVC | EVC = Sandstone Ridge Shrubland (LC); CMA = Mallee; Bioregion = Lowan Mallee; M CLIMATE potential. It occurs in bushland (Abell 2005), mountainous terrain growing between rocks and even in depressions on sheets of sandstone rock (Jamieson 2004) and can grow in wetlands (Zurita et al. 2009), it is also clump forming (Hitchmough 1989) Major displacement of some dominant spp. within a strata/layer | mh | h |

| 11. Impact on structure? | It occurs in bushland (Abell 2005), mountainous terrain growing between rocks and even in depressions on sheets of sandstone rock (Jamieson 2004) and can grow in wetlands (Zurita et al. 2009), it is also clump forming (Hitchmough 1989) – minor effect on 20-60% of the floral strata | ml | mh |

| 12. Effect on threatened flora? | Although it occurs in bushland in remnant endangered ecological community, Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest (Abell 2005), it’s impact on VROT and Bioregional Priority 1A spp is not yet determined | mh | l |

| Fauna | |||

| 13. Effect on threatened fauna? | Although it occurs in bushland in remnant endangered ecological community, Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest (Abell 2005), it’s impact on VROT and Bioregional Priority spp is not yet determined | mh | l |

| 14. Effect on non-threatened fauna? | It occurs in bushland (Abell 2005), mountainous terrain growing between rocks and even in depressions on sheets of sandstone rock (Jamieson 2004) and can grow in wetlands (Zurita et al. 2009), it is also clump forming (Hitchmough 1989) – reduction in habitat for fauna spp. | mh | mh |

| 15. Benefits fauna? | Rated as having low palatability to goats (MLA 2007) and “plants seem to be immune to the predations of rabbits” (PFAF 2009). As it is evergreen (Harrison 2006) and forms clumps (Hitchmough 1989) it may provide some shelter for small spp. but is unlikely to provide food – provides some assistance in either food or shelter to desirable species | mh | m |

| 16. Injurious to fauna? | Causes skin rashes and may cause damage to eyes, mouth and throat on contact to people (Toronto Botanical Garden 2009), however is not known to be toxic to fauna – no effect | l | ml |

| Pest Animal | |||

| 17. Food source to pests? | “Plants seem to be immune to the predations of rabbits” (PFAF 2009) and is rated as having low palatability to goats (MLA 2007) – provides minimal food for pest animals | l | m |

| 18. Provides harbor? | As it is evergreen (Harrison 2006) and forms clumps (Hitchmough 1989) it has capacity to harbour rabbits or foxes at low densities or as overnight cover | mh | m |

| Agriculture | |||

| 19. Impact yield? | Not listed as a weed of agriculture (Randall 2007) – little or negligible affect on quantity of yield | l | m |

| 20. Impact quality? | Not listed as a weed of agriculture (Randall 2007) – little or negligible affect on quality of yield | l | m |

| 21. Affect land value? | Not listed as a weed of agriculture (Randall 2007) – little or none | l | m |

| 22. Change land use? | Not listed as a weed of agriculture (Randall 2007) – little or none | l | m |

| 23. Increase harvest costs? | Not listed as a weed of agriculture (Randall 2007) – little or none | l | m |

| 24. Disease host/vector? | Extracts from the aerial part of the plant were found to have antifungal properties against plant pathogens (Tegegne et al. 2008). “Nonchalant about pests and diseases and seem almost entirely free of them” i.e. Agapanthus spp. (Hitchmough 1989) – little or no host | l | mh |

Invasive

QUESTION | COMMENTS | RATING | CONFIDENCE |

| Establishment | |||

| 1. Germination requirements? | “Seeds of both subspecies [i.e. Agapanthus africanus subsp. walshii and subsp. africanus] germinate successfully within three weeks when sown directly after harvesting” (Duncan 2004). “Seeds can be sown fresh in late summer (or store them in the refrigerator until spring)” (Harrison 2006) – requires natural seasonal disturbances such as seasonal rainfall, spring/summer temperatures for germination. | mh | m |

| 2. Establishment requirements? | “Timing is not critical when planting” i.e. Agapanthus spp. (Hitchmough 1989) and grows in sun to partial shade (Harrison 2006) – can establish under moderate canopy/litter cover | mh | m |

| 3. How much disturbance is required? | Occurs in bushland in remnant endangered ecological community, Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest (Abell 2005) – establishes in healthy and undisturbed natural ecosystems | h | h |

| Growth/Competitive | |||

| 4. Life form? | Tuberous rootstock i.e. Agapanthus spp. (Hitchmough 1989) – geophyte | ml | m |

| 5. Allelopathic properties? | No allelopathic properties referred to in the literature (Hitchmough 1989) | l | m |

| 6. Tolerates herb pressure? | Rated as having low palatability to goats (MLA 2007) and “plants seem to be immune to the predations of rabbits” (PFAF 2009), although “baboons and buck sometimes eat the flower heads just as the first flowers begin to open” (Jamieson 2004) – favoured by heavy grazing pressure as not eaten by animals/insects and not under a biological control program in Australia/New Zealand | h | m |

| 7. Normal growth rate? | Average growth rate (NGA 2009) – growth rate equal to the same life form | m | ml |

| 8. Stress tolerance to frost, drought, w/logg, sal. etc? | “Survived under permanent flooding conditions during 12 months” (Zurita et al. 2009) and “in irrigated soils Agapanthus grow and flower far more profusely” i.e. Agapanthus spp. (Hitchmough 1989). “They grow from a fleshy rootstock and have masses of big fleshy roots which enable them to stand long periods without water” i.e. Agapanthus spp. (van der Spuy 1971). Tolerate drought i.e. Agapanthus spp. (van der Spuy 1971). “Although a light frost is tolerated, protection may be needed if the temperature drops below 20˚F” (Harrison 2006) and died at -5˚C (Matsubara et al. 2003). “Often it is selected for planting in difficult seaside gardens because of its salt tolerance and ability to stand up to the wind” – moderate salt tolerance (Harrison 2006). “Blooms profusely after veld fires” (Burman, Bean 1985). Tolerant to waterlogging, drought and fire. Moderately tolerant to salt. Slightly tolerant to frost. | h | m |

| Reproduction | |||

| 9. Reproductive system | “the roots multiply from year to year, giving rise to new plants and eventually the plants begin to suffer through being overcrowded” i.e. Agapanthus spp. (van der Spuy 1971) also produces viable seed (Harrison 2006) – both vegetative and sexual reproduction | h | m |

| 10. Number of propagules produced? | About 80 flowers per plant [from image, p. 212] (Duncan 2004) – however number of seeds is unknown | m | l |

| 11. Propagule longevity? | Unknown | m | l |

| 12. Reproductive period? | “Lift and divide every four or five years to ensure flowering” (Harrison 2006) – perennial – mature plant produces viable propagules for 3-10 years | mh | m |

| 13. Time to reproductive maturity? | “Generally flowers for the first time in their third year” [i.e. Agapanthus africanus subsp. walshii and subsp. africanus] (Duncan 2004). “the roots multiply from year to year, giving rise to new plants” i.e. Agapanthus spp. (van der Spuy 1971) – vegetative propagules become separate in under one year | h | mh |

| Dispersal | |||

| 14. Number of mechanisms? | “The seed which is often parasitized is dispersed by the wind” (Jamieson 2004). Agapanthus africanus subsp. walshii seeds are winged (Duncan 2004) – very light, wind dispersed seeds | h | mh |

| 15. How far do they disperse? | “The seed which is often parasitized is dispersed by the wind” (Jamieson 2004). Agapanthus africanus subsp. walshii seeds are winged (Duncan 2004) – very likely that at least on propagule will disperse greater than one kilometre | h | mh |

References

Abell R (2005) Bush regeneration at Paddy Pallin Reserve: A comment on the importance of reliability and flexibility of funding to deliver ecological outcomes. Ecological Management & Restoration 6(2), 143-145.

Burman L, Bean A (1985) Hottentots Holland to Hermanus; South African Wild Flower Guide 5. Botanical Society of South Africa.

Duncan G (2004) Agapanthus africanus subsp. walshii. Curtis’s Botanical Magazine 21(3), 205-214.

Harrison M (2006) Groundcovers for the South. Pinapple Press Inc.

Hitchmough J (1989) Garden bulbs; A seasonal planting and flowering guide for all Australian regions. Viking O’Neil.

Jamieson R (2004) Agapanthus africanus. South African National Biodiversity Institute. Available at http://www.plantzafrica.com/plantab/agapanafric.htm (verified 19 February 2009).

Matsubara K, Inamoto K, Doi M, Imanishi H (2003) Evaluation of cold hardiness of some geophytes for landscape planting. Scientific Report of the Graduate School of Agriculture and Biological Sciences 55, 37-41.

Meat and Livestock Australia (MLA) (2007) Weed control using goats; a guide to using goats for weed control in pastures. NSW Department of Primary Industries. Available at

http://www.mla.com.au/NR/rdonlyres/AE169A4C-60E2-4DC2-A454-4C5B648C727E/0/LPI010WeedcontrolusinggoatsMay2007.pdf (verified 18 February 2009).

National Gardening Association (NGA) (2009) NGA Plant finder. NGA, South Burlington, VT. Available at

http://www.garden.org/plantfinder/index.php?q=view&id=66&sort[]=botanical&sort_order[]=botanical (verified 19 February 2009)

Plants for a Future (PFAF) (2009) Agapanthus africanus. Available at http://www.ibiblio.org/pfaf/cgi-bin/arr_html?Agapanthus+africanus&CAN=LATIND (verified 18 February 2009).

Randall R (2007) Global compendium of weeds; Agapanthus africanus. Available at http://www.hear.org/gcw/species/agapanthus_africanus/ (verified 19 February 2009)

Rodríguez P, OS (1997) Hedgerows and mulch as soil conservation measures evaluated under field simulated rainfall. Soil Technology 11, 79-93.

Shepherd RCH (2004) Pretty but poisonous; plants poisonous to people; An illustrated guide for Australia. RG and FJ Richardson, Melbourne.

Tegegne G, Pretorius JC, Swart WJ (2008) Antifungal properties of Agapanthus africanus L. extracts against plant pathogens. Crop Pretection 27, 1052-1060.

Toronto Botanical Garden (2009) Poisonous/Toxic Plants. Available at http://www.torontobotanicalgarden.ca/mastergardener/PoisonousToxicPlants.shtml (verified 19 February 2009).

Van der Spuy U (1971) Wild flowers of South Africa for the garden. Hugh Keartland Publishers.

Zonneveld BJM, Duncan GD (2006) Genome size for the species of Nerine Herb. (Amaryllidaceae) and its evident correlation with growth cycle, leaf width and other morphological characters. Plant Systematics and Evolution 257, 251-260.

Zurita F, De Anda J, Belmont MA (2009) Treatment of domestic wastewater and production of commercial flowers in vertical and horizontal subsurface-flow constructed wetlands. Ecological Engineering 35(5), 861-869.

Global present distribution data references

Australian National Herbarium (ANH) (2009) Australia’s Virtual Herbarium, Australian National Herbarium, Centre for Plant Diversity and Research, Available at http://www.anbg.gov.au/avh/ (verified 19 February 2009).

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) (2009) Global biodiversity information facility, Available at http://www.gbif.org/ (verified 19 February 2009).

Feedback

Do you have additional information about this plant that will improve the quality of the assessment?

If so, we would value your contribution. Click on the link to go to the feedback form.