Victorian Grain Cropping Soils - Sandy Soils

Back to: Soils of Victorian Grain Cropping Regions

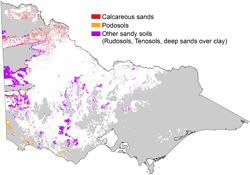

| Nature and Distribution This broad group consists of a diverse range of soils that are predominantly sandy (particularly in the upper 50 cm of the soil profile). |  |

| Podosols Podosols are mainly sandy throughout with accumulations of organic materials and aluminium (with or without iron compounds), often referred to as “coffee rock”, in the subsoil. They typically have deep bleached sand horizon overlying the coffee rock. They are not a common grain cropping soil, occurring mostly in the far south-west of Victoria and south of the Little Desert. |  |

| Calcareous sands Calcareous sands are a major grain cropping soil, commonly occurring in the Mallee region, associated with east-west trending dunes. They are calcareous throughout, with visible accumulations of calcium carbonate (lime), as soft or hard fragments, increasing with depth. Soil pit site MP3 is an example of a sandy Calcarosol near Walpeup. |  Site MP3 Profile |

Other sandy soils (Tenosols, Rudosols and texture contrast soils with deep sandy surface horizons)

Deep sands (that are technically classified as Rudosols or Tenosols in the Australian Soil Classification) are commonly found on sand sheets and dunes in the Wimmera and Mallee regions. These are not dominated by calcium carbonate throughout (as are Calcarosols) and range from being acidic to slightly alkaline.

| Deep sands with little profile development occur in the Big Desert region, usually associated with high parabolic shaped dunes. There is often little soil development, apart from surface accumulation of organic matter. These soils are generally classified as Rudosols in the Australian Soil Classification. As well as occurring in the Big Desert, these soils can also occur further south. |  A Rudosol that occurs in some younger Big Desert dunes near Walpeup. |

| In some parts of the landscape (although more common in the Mallee region) are areas of land with east-west trending dunes. These soils are sandy throughout with a dark surface horizon overlying a strongly bleached subsurface horizon and a brighter coloured sandy subsoil horizon (which is usually slightly harder than the surface horizons and may have clay banding). These soils can vary between moderately deep to very deep (i.e. 1-6 metres) and are generally referred to as Tenosols in the Australian Soil Classification (being better developed than Rudosols). These soils are associated with sand dunes and sand hills which are commonly found on the undulating sand plains west of Dimboola (i.e. Little Desert) and north of Nhill and Kaniva. They also occur on many of the dissected sand dunes which are scattered on the undulating plains west of Natimuk. These soils also occur in association with sands over clay. |  A Tenosol with argic horizons associated with older dunes in the Big Desert. |

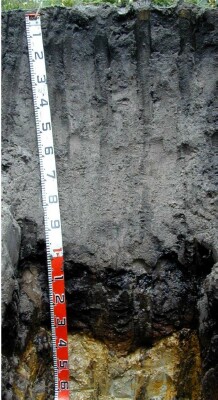

| Soils with thick sandy surface horizons overlying clayey subsoils are also included in the sandy soils category. These soils are commonly found on sand sheets, low dunes and hill slopes in the Wimmera and southern Mallee regions and may occur in association with other deep sandy soils such as Podosols. They are characterised by thick sandy surface horizons (50 cm or greater in depth) overlying a mottled clay subsoil (that is often sodic). These texture-contrast soils are classified as either Sodosols, Chromosols or Kurosols in the Australian Soil Classification, but are included in the Sandy Soils category as the deep sandy surface horizons are a key management consideration for cropping. |  Example of a sandy soil near Kaniva |

Management Considerations

Sandy soils in general

Plant Available Waater Capacity (PAWC) and inherent fertility are generally low for sandy soils. However, with adequate water, fertilisers and additional organic matter they will become more productive. The low wilting point value indicates that plants will be able to utilise light rains falling on relatively dry soils. However, due to the low water storage capacity, plants will soon suffer moisture stress unless further rainfall occurs. Organic matter is important in sandy soils to enhance water holding capacity.

The weakly structured and loose nature of sands considerably increases the risk of wind and water erosion. Any soil lost through wind or water erosion removes nutrients and decreases the depth of soil from which plants can effectively access nutrients and water. The risk of erosion is increased by the absence of adequate groundcover. Cultivation is not recommended and the loose nature of the surface soils makes them well suited to direct drilling and stubble retention. High moisture loss is possible with cultivation (including the sowing operation) and some compaction may be needed to provide a firm seedbed.

The surface of some sandy soils can be naturally non-wetting or water-repellant due to hydrophobic ‘skins’, formed by waxes and other products created from decomposition processes, coating sand grains. Water tends to pool on the surface or run-off, limiting availability to the crop. Water can also move down preferred pathways (‘biopores’ created by plant roots and animals) and infiltrate beneath the surface, but this can also lead to uneven wetting. Sandy surface horizons are usually well drained once water enters the soil profile. Further information can be found in the publication Management of water repellent sands in the Southern cropping region prepared by Murray Unkovich et al (2015) for GRDC which is available on the CSIRO website.

Podosols and deep acid sands

Podosols are strongly leached sandy soils that are poor in nutrients and acidic to strongly acidic throughout. They are characterised by having variably cemented iron and humus accumulations in the subsoil (often referred to as ‘coffee rock’). The ‘coffee rock’ layer may restrict the downward movement of plant roots and water. In some situations though, the build-up of water on top of the less permeable layer may be beneficial in that it prevents deep drainage of water away from plant roots. In areas lower in the landscape, waterlogging could occur.

Strongly leached soils are also likely to be naturally deficient in nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur and potassium. Regular fertiliser inputs are required for improved pasture or cropping. Nitrate and sulphate are readily soluble and easily removed by leaching. More regular but smaller applications of fertiliser will assist in reducing loss of nutrients through leaching and is likely to be deficient in nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. The bleached sub-surface (A2) horizon is extremely infertile, so building up the surface (A1) horizon should be an objective.

Lime application results in increased pH levels and makes certain nutrients such as phosphorus and molybdenum more available to plants. Nutrients such as calcium and magnesium are also usually low in strongly acid soils. Magnesium deficiency can be assessed by plant tissue analysis and treated by applying dolomite to the soil or using a foliar spray. The trace element boron (B) leaches rapidly through acid sandy soils and deficiencies are likely to occur. Over-liming in sandy soils can make trace elements such as boron, zinc and manganese less available. Organic matter can complex with metal ions enabling trace elements (Fe, Zn, Cu) to become more available to plants.

Deficiencies in the trace element molybdenum (Mo) are likely to occur in acidic sandy soils (soil adsorption of Mo increases as pH decreases, leading to reduced availability to plants), but should be confirmed by plant tissue analysis. Deficiencies can be remedied with molybdenum-enriched fertiliser and foliar application.

Sands over clay

When wet, the sandy textured surface soils are highly permeable but permeability of water into the subsoil can be restricted by hardpans and sodic subsoils. As a consequence, lateral flow of water along the top of the subsoil will reduce available water for use by plants and exacerbate degradation problems lower in the landscape (e.g. waterlogging). Subsoil clays have moderate water storage capacity but often much of the water remains unavailable to plants if roots are restricted by poor soil structure.

Retaining vegetation cover and minimising soil disturbance will assist in improving soil structure and increasing the water holding ability of the surface horizons. Deeper-rooted perennial pastures may assist in opening up the clay subsoil over time. Deep rooted annual crops are less likely to benefit the structure of the subsoil due to the depth to subsoil.

Sandy soils allow for good root development in the surface soil but poor fertility may reduce plant size. Roots will penetrate to depth seeking moisture and nutrients. Most annual crops and pastures are unlikely to have significant root growth impeded by deeper impermeable clay horizons (at depths greater than 50 cm).